Planning before a flight in a low-stress environment can help a pilot produce a safe strategy for the flight – in other words the pilot can be proactive and plan ahead to select a safe route and establish “decision points” during each flight phase. Collaborative decision-making with ATC, weather services, and other pilots will help to size up a general situation. Good pre-flight planning also reduces the workload once airborne.

Feature

Radio Telephony

Talking Radio Telephony

Talking Radio Telephony is a podcast from the CAA featuring David Woodward and Anthony Hatch, whose work with Local Airspace Infringement Teams, along with their pilot, FISO, ATCO, flight instructor and RT examiner experience, led them to want to start a conversation about Radio Telephony (RT).

Radio Telephony (RT) is a very important element of effective pre-flight route planning and, if done correctly, will allow for a safe and expeditious flight and not pose as a distraction in flight. As mentioned earlier in the Route Planning section of this tutorial, a respected flight instructor once said, “Do not fly a route that you have not first flown on your dining room table” and this applies to the use of RT also. Planning exactly where you are going to contact the next Air Traffic Service Unit (ATSU) along your route will allow you to plan your transmissions and always make use of the most appropriate Air Traffic Service (ATS). This guidance has been written by a current Flight Instructor and Flight Radio Telephony Operators Licence (FRTOL) Examiner.

Why is Radio Telephony important?

In short, RT is an aid to safety. It can act as another pair of eyes by allowing all airspace users to build a 3D picture of what it is happening in the airspace around them; not just at one moment in time but also how the airspace is likely to look in the near future. This can be achieved by using the standard initial call in the air when making initial contact with an ATSU. The initial call should be in the following format.

- Ground station callsign

- Aircraft callsign

- Request

Only when two-way communications has been established with the ground station should you pass the following information. The ground station may say “pass your message”.

- Aircraft callsign

- Aircraft type

- Departure point

- Destination

- Position

- Level

- Additional information

Your additional information should contain your routing details that relate to the portion of the flight while you are communicating with this specific ground station. For example, on a flight from Goodwood to Caernarfon, Farnborough Radar are unlikely to need to know your planned routing over North Wales but it would be useful for them to know your planned routing while you are operating within their LARS area so they are able to pass relevant traffic and airspace activity information to you. An example of such an initial call is:

“Farnborough Radar, G-ABCD, request Traffic Service.”

“G-ABCD, Farnborough Radar, pass your message.”

“G-ABCD, Cessna 172, Goodwood to Caernarfon, 3 miles east of VRP Butser Hill Mast, altitude 3,700 feet, routing via Compton, VFR.”

This routing information may prompt the controller at Farnborough to remind the pilot that Lasham Glider Site is active. The pilot should know this information already as they should have identified Lasham as a Threat during their pre-flight planning but the information from Farnborough serves as a reminder to be cautious as to their proximity to the site.

Furthermore, obtaining a service from the most relevant ATSU for your area of operation will ensure you have the correct QNH set for the airspace you are operating in and proximate to. The Airspace Infringement Team at the CAA has noted that several infringements of CTAs and TMAs occur because pilots are operating on an inappropriate or incorrect pressure setting, such as the Regional Pressure Setting (RPS), when operating proximate to controlled airspace. As pilot in command, you do not have to accept an RPS if you deem it inappropriate for your operation. Do not be afraid to request the QNH.

Radio planning while route planning

An earlier section explained the importance of thorough pre-flight planning incorporating regulated sources of information, such as the UK AIP and VFR charts, and application of effective Threat and Error Management (TEM). The same is true for RT and it is important to incorporate radio planning into your route planning. For example, deciding which is the most appropriate ATSU on each sector of your route as well as deciding the most appropriate service to request based on the limitations of the licence and equipment of the ATSU you are talking to, and the day and time that your flight is going to take place.

Once you have completed your pre-flight route planning as shown in the section of this tutorial, it is time to start considering who you will request a service from, the type of service that you will ask for and where you will make your radio calls.

It is good practice to apply the following order of priority during your flight planning when it comes to deciding who to request a service from:

- If within 10NM of an aerodrome with a suitable ATS (FIS/ATC), or underneath their airspace, or within 15NM or 5 minutes flight time, whichever is the sooner for a MATZ obtain a service, from that Unit. If not,

- If there is a Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS) available, obtain a service. If not,

- Utilise an appropriate Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) where available. If not,

- Obtain a service from London or Scottish Information.

The above guidance does require some flexibility especially with airfields which are proximate to other airfields or controlled airspace.

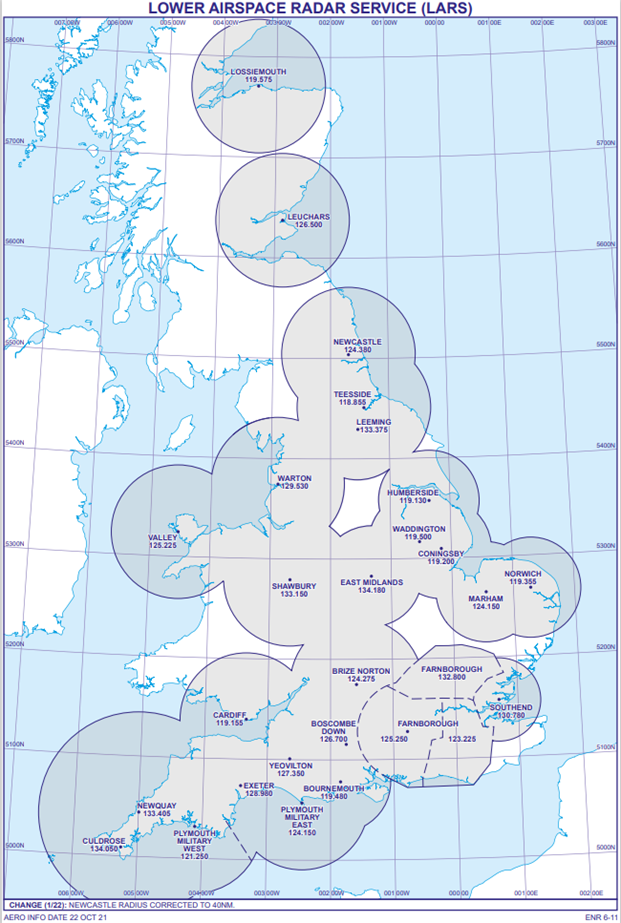

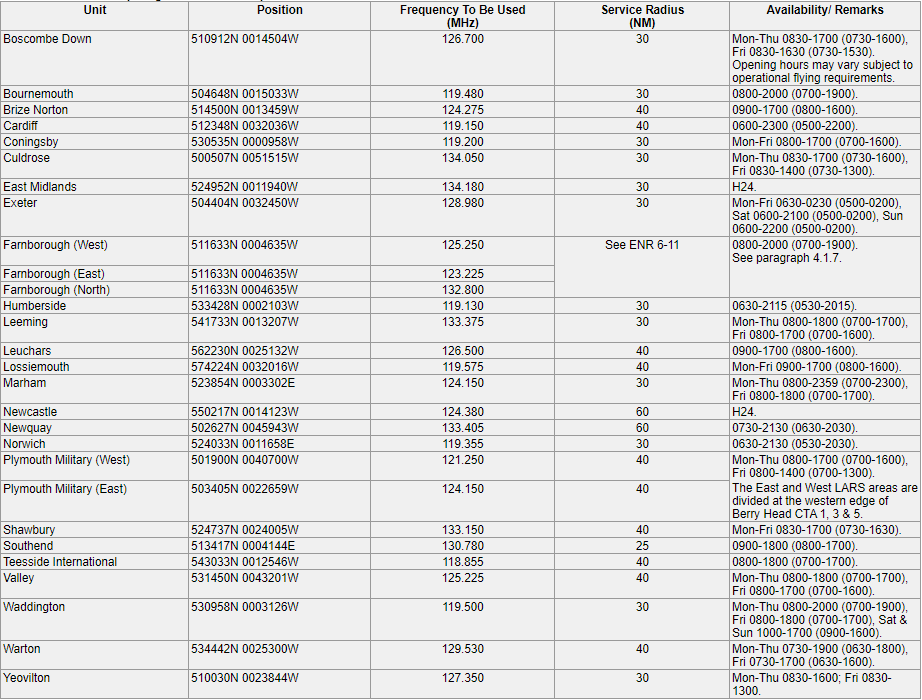

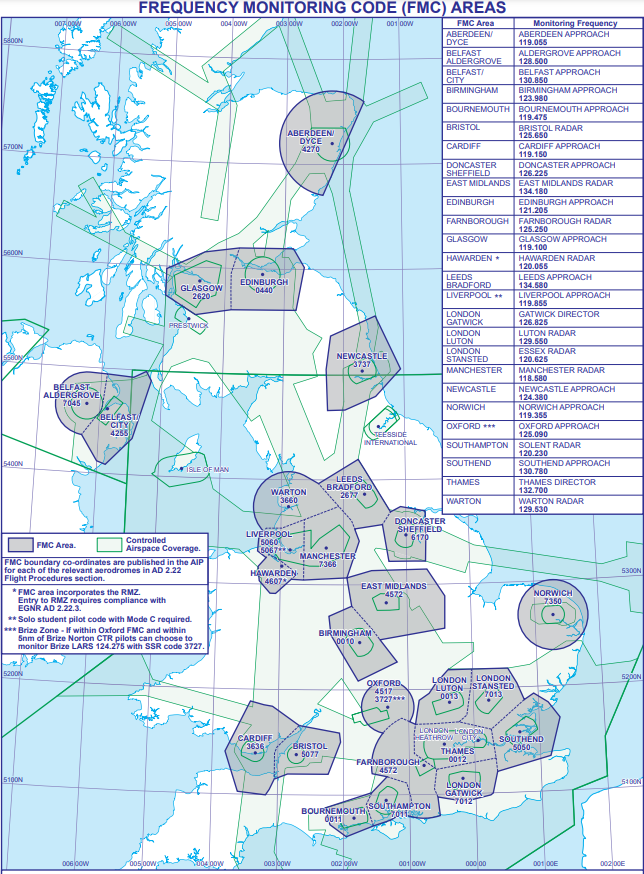

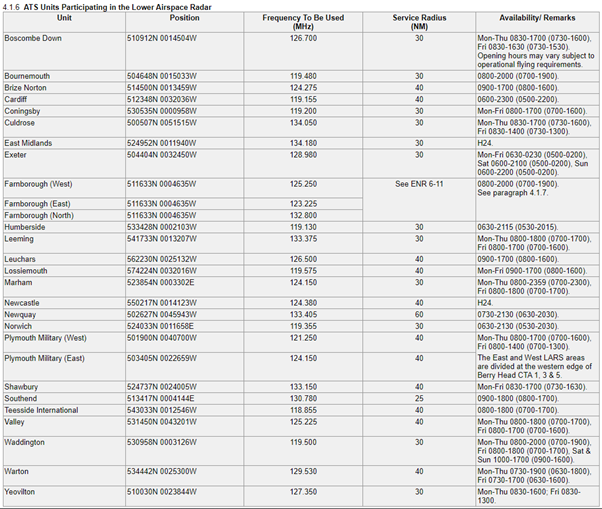

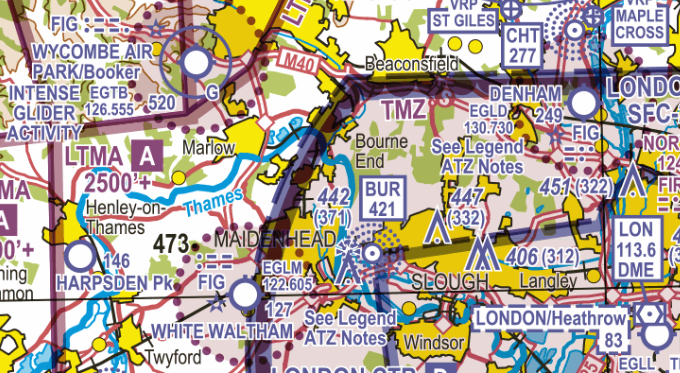

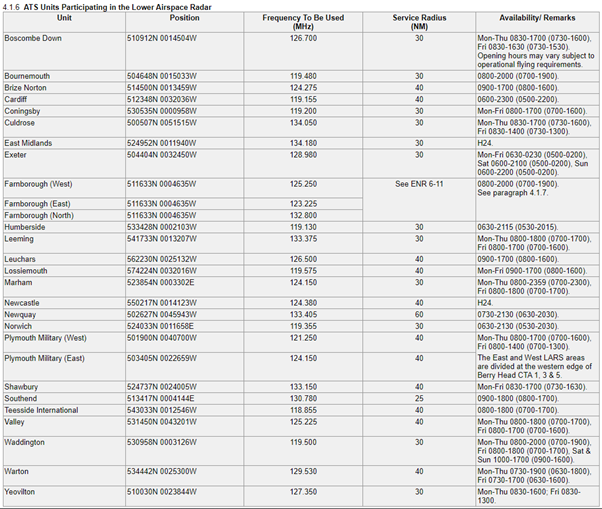

The Designated Operational Coverage (DOC) of all ATSUs can be found in the UK AIP under the relevant aerodrome in section AD 2. LARS coverage including service radius, service area, and operational hours can be found in the UK AIP ENR 1.6 ATS SURVEILLANCE SERVICES AND PROCEDURES and a chart showing LARS coverage areas is also available at ENR 6-11.

Example – ENR 1.6 ATS SURVEILLANCE SERVICES AND PROCEDURES – ATS UNITS PARTICIPATING IN LOWER AIRSPACE RADAR.

The above guidance does require some flexibility especially with airfields which are proximate to other airfields or controlled airspace. The Designated Operational Coverage (DOC) of all ATSUs can be found in the UK AIP under the relevant aerodrome in section AD 2. LARS coverage including service radius, service area, and operational hours can be found in the UK AIP ENR 1.6 ATS SURVEILLANCE SERVICES AND PROCEDURES and a chart showing LARS coverage areas is also available at ENR 6-11 (see below).

Information on the notified areas of London Information and Scottish Information including their vertical limits, times of availability and frequencies can be found in UK AIP ENR 6-32 LONDON ACC – FIS SECTORS and ENR 6-33 SCOTTISH ACC FIS SECTORS.

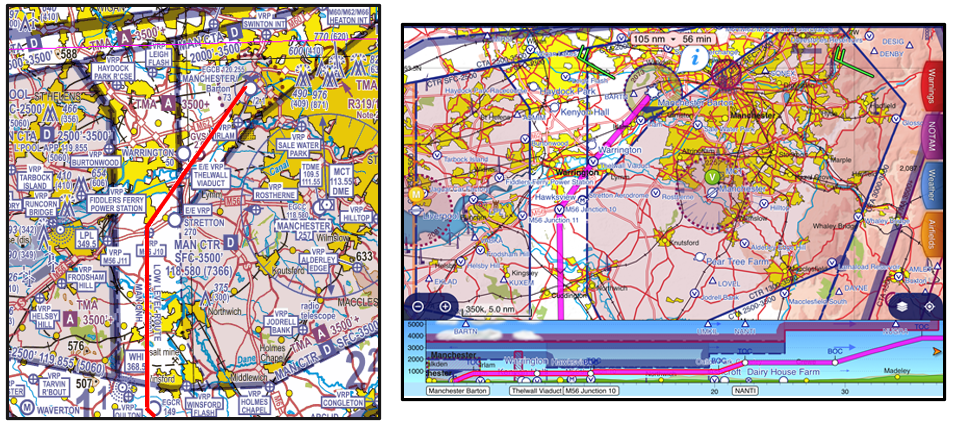

Local flight example

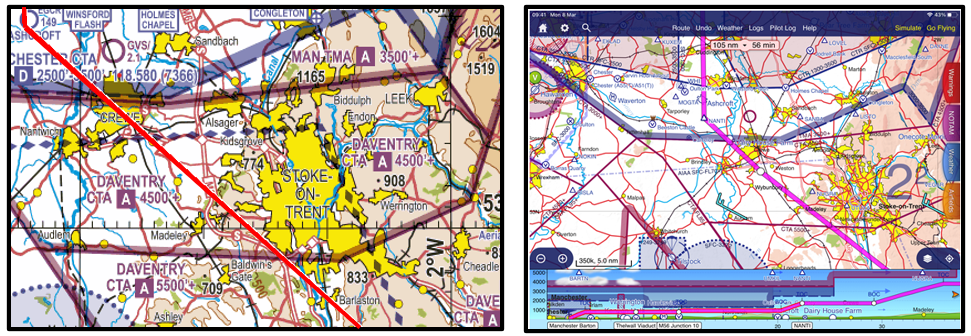

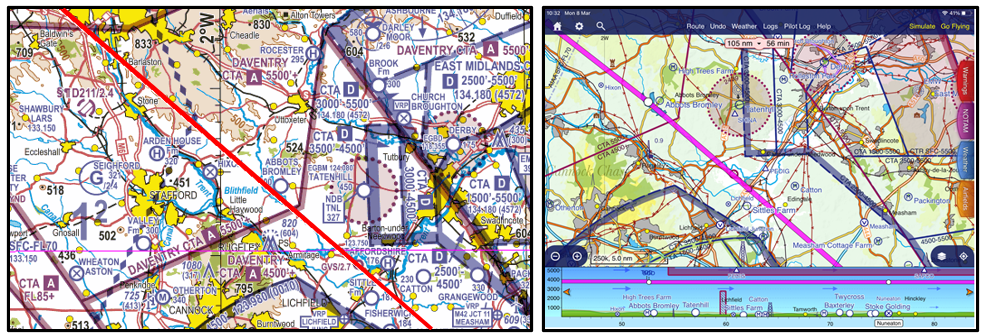

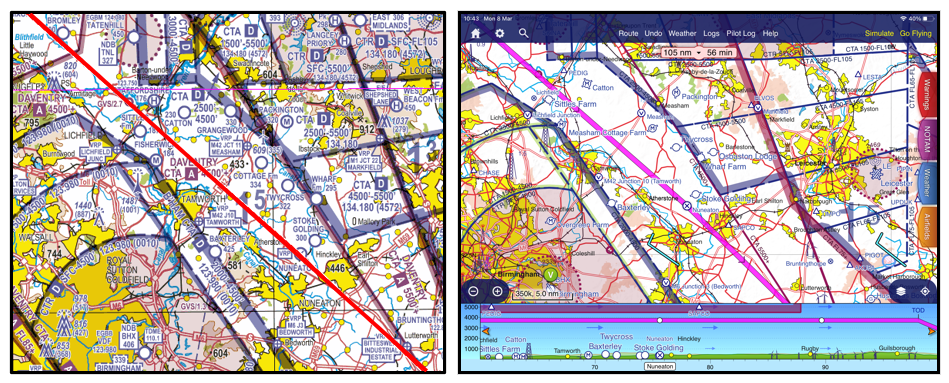

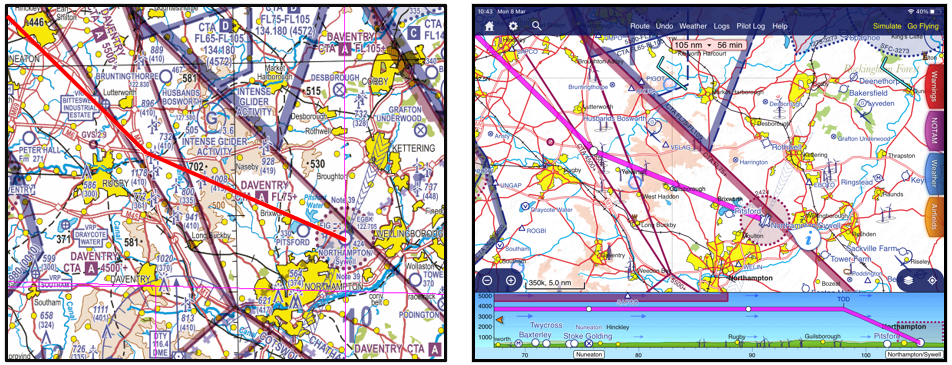

The following example of a local flight from Manchester Barton to Manchester Barton via Accrington, Settle, Lancaster, and Middlebrook Stadium Visual Reference Point (VRP) will detail the process of applying the above guidance and how best to mark this on your chart.

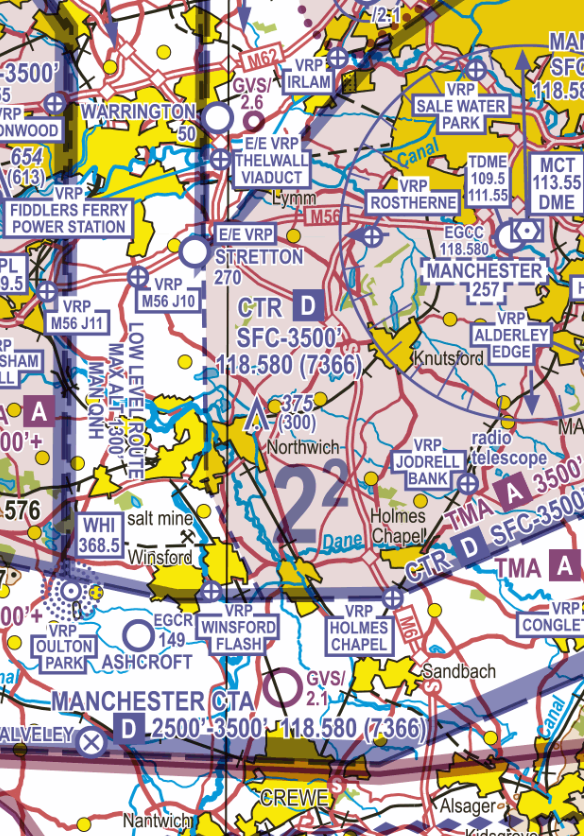

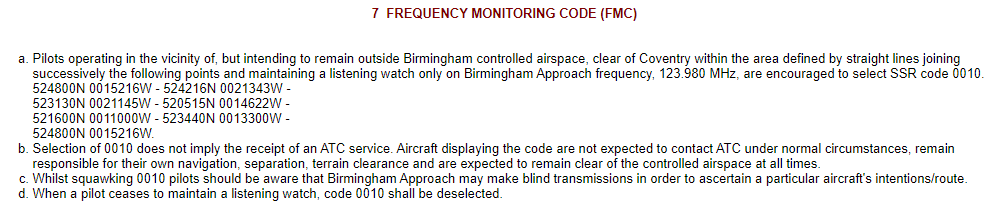

Once you have chosen your routing you can start to annotate your frequency changes on the chart. Using the above guidance, a Basic Service will be obtained from Barton Information until 10NM away from the aerodrome. At this point you should be planning to change from the Barton frequency and deciding which frequency you will be changing to next. In this case, you will still be operating underneath the Manchester TMA; therefore, monitoring Manchester Radar on 118.580 MHz and selecting the Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) 7366 would be suitable. Information on the areas in which FMCs can be used can be found in UK AIP ENR 6-80 FREQUENCY MONITORING CODE (FMC) AREAS and on the FMC card.

Further along the route, you are no longer going to be operating underneath the Manchester TMA and will be continuing to head away from the controlled airspace; therefore, it would be prudent to change to a new frequency. Looking at the priority list, you will not be within 10NM of an aerodrome therefore you would move to point 2 on the list. By checking the UK AIP, you note that Warton provide a LARS up to 40NM between specified times during the week. Your flight is due to take place during those times and there is not a NOTAM in force which notifies Warton LARS as not available. Based on this information, Warton Radar would be best placed to provide you with a service and a symbol should be placed on your chart, in this case at Accrington. Running your finger along your route, you note that the rest of your flight will take place within 40NM of Warton, and you can see that you will not pass within 10NM of an aerodrome that is able to provide you with a service (other than Warton) for most of your flight until you reach Barton again. Taking your navigation ruler, measure 10NM from the Barton ATZ and annotate your chart with a frequency change symbol.

After a double check, you are satisfied with your plan therefore you should now start to number your frequency changes. Frequency number 1 will always be the one for your departure aerodrome, in this case Barton, and the numbers should run in chronological order along your route. If you have decided that you are going to talk to the same ATSU twice then you should use a separate number for both occasions to keep the chronology correct.

You should also mark any major points along your route such as geographical limit points before the edge of airspace. In the case of this flight, you could place a marker 15NM from the edge of the Warton MATZ to remind you to request a MATZ penetration (MP) service in good time. A limit point should also be placed prior to the edge of the Barton ATZ to remind you to not proceed beyond that point without having satisfied the requirements of Rule 11 (4) of The Rules of the Air Regulations 2015.

Your PLOG should reflect the plan you have created on the chart and should include the ground station callsigns, frequencies, any FMCs, and the service you are going to request such as in the example table below. You can also anticipate the squawk codes you may be allocated by checking the squawk code allocation at UK AIP ENR 1.6 during the planning stages. At the time of writing this tutorial, Barton is allocated 7365 and Warton is allocated 3641 – 3657 therefore you can anticipate, and note down, the first two digits of the squawk code you expect from Warton Radar on your PLOG. It is important to remember that you cannot select one of these squawk codes unless directed to do so by the ATSU, unless of course, it is an FMC.

| Number | Callsign | Frequency | Squawk | Request |

| 1 | Barton Information | 120.255 | 7365 | Taxi |

| 2 | Manchester Radar | 118.580 | 7366 | FMC |

| 3 | Warton Radar | 129.530 | 36__ | Traffic Service |

| 4 | Barton Information | 120.255 | 7365 | Basic Service and Join |

Prior to conducting the flight, you should ‘fly’ the route at your planning table and practise your initial calls and responses. This will ensure that you are as prepared as possible for the RT aspects of your flight and will reduce the amount of thinking you have to do in the air in relation to your radio. For example, at Number 2, your initial call in the air should be:

“Warton Radar, GABCD, request Traffic Service.” Once two-way communications have been established you may pass your reply. Warton Radar may say, “pass your message”.

“GABCD, PA28, Barton to Barton, Accrington, altitude 3,200 feet, routing via Settle, Lancaster, and VRP Middlebrook Stadium, VFR.”

Planning conducted prior to a flight in a low stress environment can enable a pilot to produce a safe strategy for the flight (in other words the pilot can be proactive and plan ahead to select a safe route and establish “decision points” during each flight phase). Collaborative decision-making with ATC, weather services, and other pilots will help to size up a general situation. Good pre-flight planning also reduces the workload once airborne. Part of that planning should be contingency planning to be able to react calmly and efficiently if an en-route diversion becomes necessary due to insufficient fuel to reach your destination with an adequate reserve, deteriorating weather or an un-well passenger.

As GA pilots, the eagerness to return to flying after a prolonged time away is understandable. The opportunity to go flying, enjoying the views below, to travel to other parts of the country, visit friends, practice skills and the challenges associated with flying is not underestimated. Previous articles in this series highlighted the use of Frequency Monitor Codes (FMCs) and UK Flight Information Services as an essential part of planning your flight. Let’s not underestimate time spent on planning the flight can easily reduce your workload once in the air. There is the phrase about poor planning and performance.

Do we still look at a chart before going flying or purely rely on the electronic flight planning software? The chart provides a ‘flat’ view of the intended track whereas the electronic can provide the side view as well. How close will you get to other aerodromes, private strips, gliding sites, restricted or prohibited areas? How high is the land, or that obstacle? The fan markers on the extended runway centreline mean something, don’t they? How do I find out if parachute dropping is taking place tomorrow? Look, that aerodrome looks like it’s now closed. All these questions can be answered with a bit or time preparing before even setting off to the aircraft.

Manchester Low Level Route

Anticipating frequency changes and expecting what is likely to be seen along the busy route can be part of the planning phase and reduce workload at the time. Has anything changed since you last flew there?

Planning a flight with a route outside controlled airspace can reduce your workload by eliminating the need to constantly change frequencies, request crossing clearances, selecting squawks and repeating your details as you change between units. The need to navigate accurately and maintain a good look out for other traffic is the core part of any flight but some of this workload can be reduced by thoroughly planning the flight beforehand. The alternative of the ‘extra pair of hands or ears’ provided by ATC can be helpful. As two flights are never the same it can be hard to provide a comparison between a second, identical, flight; one outside controlled airspace with minimal ATC interaction, if any, and one speaking to ATC with the various services available.

Many GA flights take place at aerodromes with an ATZ and many pilots will fly around to avoid without obtaining permission to enter. However, from a safety aspect, monitoring the frequency or making your presence known can only enhance safety for yourself and other pilots in the area.

Farnborough & Blackbushe

As part of planning how many pilots have refreshed their understanding of the procedures since the airspace was introduced in February 2020?

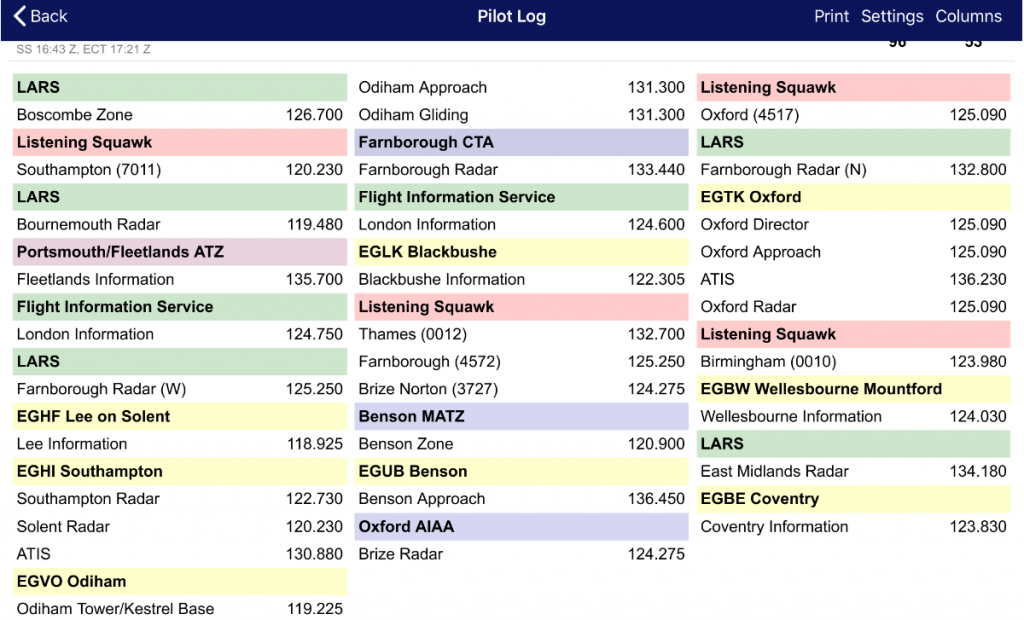

Electronic flight planning and GPS has no doubt made life easier with multiple time saving and safety related benefits, but has it meant some skills and knowledge have been lost? Fuel planning, estimates, the weight and balance are just some. The electronic radio log is a great benefit listing the correct frequencies and FMCs for the planned route. The listing of the callsigns, whether the unit is LARS, Information, or whether the airspace is a CTR, CTA, MATZ, ATZ, or AIAA is all helpful and will allow more time to concentrate on the core skills of navigating and looking-out rather than trying to work it all out as the flight continues.

Obtaining the latest meteorological information is essential and obviously the closer to the time of the flight the better. Individual preferences, recommendations from friends and other pilots how to obtain the latest and best information may vary. It is a personal choice, but it is essential. Unfortunately, every year there are reports of pilots experiencing difficulties because of weather and requiring assistance. Did they plan correctly or understand the information available?

Obtaining the latest NOTAM information is essential and if you don’t understand the content of the text or coding then why not get help from your club or another pilot? The text follows a standard international format which needs to be read and understood by pilots worldwide, which is why it sometimes appears complicated. Don’t forget a great deal has changed in the last year, with units closed or with revised operating hours, airspace declassified at certain times along with guidance on how to operate in the airspace when it is declassified and facilities that may no longer be available including fuel.

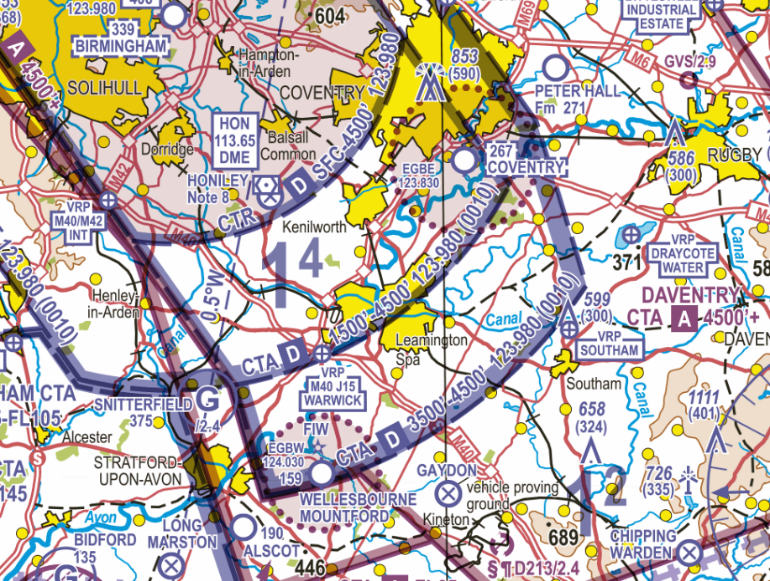

Coventry and Wellesbourne Mountford

Two examples with an ATZ under a CTA. Is there any advice or information to help avoid infringing the Birmingham CTA that is available when planning the flight?

There are probably very few smaller aerodromes who do not have a website or have their relevant information published electronically. If not, there’s always the various GA guides. The aerodromes requiring PPR, and possibly a telephone briefing prior to landing, are operating with safety in mind. It’s not only for your safety but also for the other pilots who will be operating to ensure everyone is following the same procedures. Safety is paramount and why would you try to jeopardise your own by failing to brief and plan your flight correctly?

White Waltham and Denham

Two examples of an ATZ inside a CTR, where planning and understanding the procedures is essential.

White Waltham and Denham

Two examples of an ATZ inside a CTR, where planning and understanding the procedures is essential.

The past year has meant many units have revised their operational hours due reduced traffic levels and reduced the available services with staffing restrictions in control rooms. This was especially noticeable during the ‘lockdowns’ when GA activity was minimal. Therefore, the available services may be restricted for some months as operational control rooms continue to maintain social distancing restrictions and stringent hygiene protocol with less staff available. A NOTAM check should make us aware those units affected and ensure none of us are surprised when enjoying the blue skies again this summer.

Ask yourself the question ‘Can I really say, I’m Safe?’

I ILLNESS Are you well enough to fly?

M MEDICATION Side effects, covering problems?

S STRESS Any pressure, passengers, annoyed?

A ALCOHOL Less than 25% of UK driving limit!

F FATIGUE Enough sleep, well rested?

E EATING Blood sugar correct?

Some Hazardous Pilot attitudes

| Hazardous Attitude | Antidote |

| Anti-authority – “Don’t tell me”/ ”The regulations are for someone else” | “Follow the rules, they are that way for a reason” |

| Impulsivity – “I must act now, there’s no time” | “Not so fast, think first” |

| Invulnerability – “It won’t happen to me” | “It could happen to me” |

| Macho – “I can do it!” | “Taking chances is foolish” |

| Resignation – “What’s the use?” | “Never give up. There is always something I can do” |

How can an ordinary pilot expect to survive, is it just the luck of the draw?

Here is some food for thought.

- There is a difference between skill and judgement, judgement is more important to survival than skill.

- The less skilled self-disciplined pilot is often at less risk than an experienced pilot pushing to the limit.

- If you are not aware of your personal limits, your first mistake is likely to be your last.

Are You Ready to Fly?

Documents

- Is your licence, medical and logbook up to date and valid?

- Is your insurance up to date and valid?

- Are machine’s papers valid, certificates, engineering sign offs etc

Planning

- Are your maps, charts and flight guides up to date and valid?

- Did you check and interpret for both planned flight and for possible diversions; have you followed the guidance in the next sections in this section?

- Assessed the likelihood of carburettor icing?

- What runway length do I need for this configuration?

Your machine

- Are the necessary documents on board?

- Have you completed necessary weight and balance calculations and planned aircraft loading appropriately?

- Have you created a distraction free climate for pre flight inspection?

- Are you following the POH guidance on pre flight inspection?

- Is my safety gear checked for validity, stowed correctly and accessible once the aircraft is loaded?

Finally

- Have I briefed the passenger thoroughly on emergency drills, sterile cockpit procedures and how they can contribute looking out for other aircraft?

As I close up

- Have I done as much thinking and planning on the ground so that if I meet trouble in the air I will have sufficient capacity to AVIATE, NAVIGATE and COMMUNICATE.

- Do I have the right recent experience and skill level to execute this flight safely?

Download this checklist from GASCo: GASCO Checklist

The term Threat and Error Management (TEM) is a concept that we practice in everyday life; more will be explained in later sections. The principles of TEM are to encourage pilots to have situational awareness of the risks that might put them in danger and to consider plans to mitigate those risks.

Identifying weather related risks is an important factor, so an understanding of how to manage risks such as unexpected weather changes is a fundamental part of good airmanship. Possible areas of specific risk areas are:

- Low Visibility (including Fog).

- Cloud (Low cloud base, Convective clouds etc).

- Showers and Thunderstorms.

- Wind and turbulence.

- Making the decision – pre-flight risk assessment (en-route, at destination and alternatives).

- Operating to/from/between ‘green-field’ sites.

To be able to apply effective weather related TEM, it is important to understand the difference between Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) regulated aviation meteorological products and information, and other, unregulated, sources of meteorological information.

Narrative 3 (03. Planning a weather briefing) introduced the fact that no flight should depart unless the pilot has briefed the weather using, as a minimum, regulated products, whilst also offering guidance on how to obtain met information from other sources. The CAA is the Met Authority for the UK and designates the Met Office as the UK Air Navigation Service Provider for the provision of meteorological forecasting and climatological services for civil aviation. The UK Met Authority’s objective is to supply operators, flight crew members, ATS units, airport management and other civil aviation users with the meteorological information necessary for the performance of their respective functions, thus contributing towards the safety, regularity and efficiency of air navigation. The UK Aeronautical Information Publication at GEN 3.5 describes the UK system and services available.

As with all products providing aviation related information, it is vital that a user understands not only how to use them but also understands the accuracy and validity of the information, and ,when using unregulated products, whether or not the data used is derived from the regulated source. When using weather apps – aviation and non-aviation – you’ll need to recognise the limitations and possible risks of using any of these. Some considerations include:

- Is the information provided complete?

- Is information managed effectively within the app – is only valid information displayed, and is expired information removed promptly?

- What level of data validation and verification does the provider employ?

- Does the provider identify and manage any errors effectively? (e.g. notification to users, correction of errors and facility for reporting issues).

- What measures are taken to ensure that information taken from the Met Office is not lost, altered or misrepresented?

When utilising VFR moving maps it may be useful to recall that navigation information isn’t usually coupled with weather information, and if it is, databases may not include full information. Depending on the route selected, GPS navigation could lead you to fly into adverse weather such as haze, fog, heavy rain, snow or thunderstorms. To avoid this risk carefully prepare your flight on the ground including weather recognition, and if applicable, refresh weather information during the flight.

The following section is not to ‘re-teach’ the basics about regulated products but to provide further, practical guidance to users on how to interpret and ‘read’ the forecasts and to help them to be able to use the information they contain more effectively. The intent is to reduce the number of incidents where weather has been a significant contributory factor and the information in this section is provided in order to support this objective by helping pilots to enhance their knowledge and also by helping instructors and examiners to more effectively assess the level of pilot skills in the use of weather products and weather-related decision-making.

For example:

- TAFs/METARs give the cloud based on the ground level at the reporting aerodrome.

- Values in TAFs do not represent a single forecast value but rather a range of potential values (A table describing the range of wind, cloud and visibilities that TAFs cover can be found on the Met Office website in the Pilot Resources section).

By way of a reminder, whilst planning and operating, the guidance for the suitability of the weather en-route can be found in the following regulated aviation weather briefing products:

- TAFs/METARs.

- Aerodrome Warnings.

- F214/215.

- GAMET

All regulated products are available free of charge via the Met Office Aviation Briefing Service. The Aviation Briefing Service also includes additional UK and European information such as synoptic charts, weather map viewer, observed and forecast map layers (satellite imagery, lightning and thunderstorm layers), rainfall radar and Aerodrome Warning email alert service.

Having briefed against regulated products pilots can, if necessary, contact Met Office meteorologists for further forecast clarification.

It is recommended that as pilots we enhance our confidence in weather decision-making, for example watching forecasts on TV, keeping an eye on METARs and TAFs even when not flying, studying radar and satellite imagery, talking to fellow pilots, sharing weather experiences and reading books and articles and attending aviation meteorological courses. It is also essential to review the weather-related decision-making aspects of your pre-flight risk assessment routine and to carry out post-flight analysis.

The Met Office provides a range of Pilot Resources to support the use of regulated aviation meteorological products and the GetMet publication provides further information on regulated products and how to obtain them. The UK experiences very changeable and often unseasonal weather conditions so it is vital to focus on flight safety in IMC conditions – i.e. making decisions when assessing whether, or where, to fly when IMC conditions exist or are forecast – for example, taking more time to consider potential contingency plans and diverts to support effective decision-making en-route. It is good practice to train/remain current on using basic flight instruments in case of inadvertent entry into adverse weather conditions – an event which could result in loss of control due to spatial disorientation.

In applying TEM follow the concept of ANTICIPATION – RECOGNITION – RECOVERY:

ANTICIPATION: Consider your limits and how the forecast cloud and visibility may present a threat; even if the weather seems fine, what could go wrong to spoil your day.

RECOGNITION: A safe flight depends on being able to conduct safe VFR navigation and respond to unexpected hazards conditions or the weather being as forecast or improving as forecast and not deteriorating faster than expected.

RECOVERY: At each decision point you MUST have planned actions for the eventuality that the weather has not improved or is deteriorating further on your route.

Weather-related scenarios

These case studies (based on real events) include:

- Overview – describe a proposed flight from A to B.

- Provides ‘example’ TAFs/METARs and charts for the proposed flight.

- Considers TEM in the planning and operational stage.

They relate to flying conditions that may be experienced with different air masses in the UK at different times of the year. They include risks they may pose, plus some suggested best practice mitigants and decisions that could be made.

They are also included on the Met Office website – Pilot resources – Introduction to Threat and Error Management (TEM), linked here to download:

- Case 1: High pressure – Summer flight with atmospheric convection

- Case 2: Tropical Maritime

- Case 3: Spring and Autumn

Case 1: High pressure – Summer flight with atmospheric convection

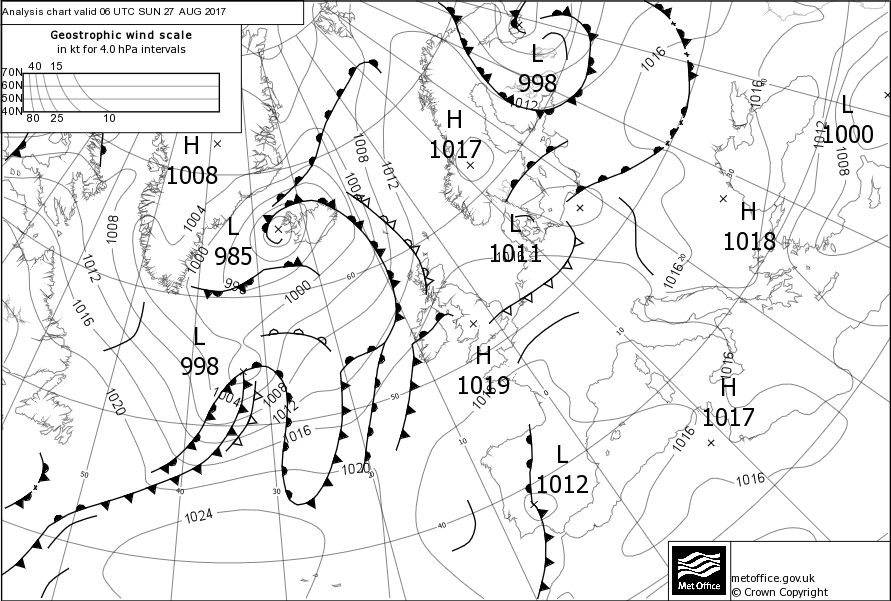

Route: Southampton to Norwich (VFR) / Date: 27 August 2017, departing 0800 hours UTC

Synoptic situation

What are the broad features in the synoptic chart, what is the main type of airmass covering the region and what kind of weather can we expect from it? How strong is the wind likely to be and what will its direction be?

The south of the UK is dominated by an anticyclone (1019 hPa), giving predominantly fair weather and gentle winds. There are not many isobars on the chart so we can assume that the winds will be light and variable although mainly north-easterly on the planned route and, when considering the time of year, it is possible for sea breezes to develop around the coasts. Looking at the wider flow, the airmass seems to have a mixture of maritime and continental influences; the air is likely to be warm and predominantly dry, generating just fair-weather clouds but with some lower cloud bases in moister air to the west. The presence of an upper cold front to the east of England complicates the picture somewhat and will need investigating. What is the cloud base associated with it? Does it produce rain and if so, how much of it is reaching the ground? How much does it affect the visibility?

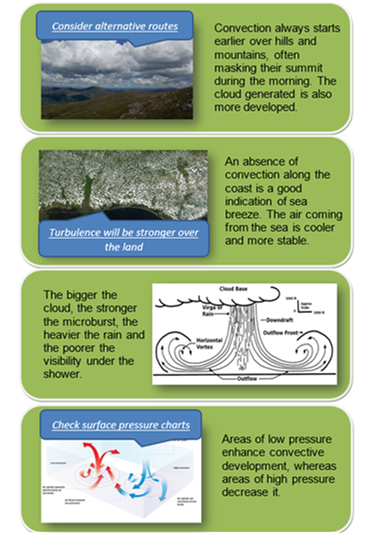

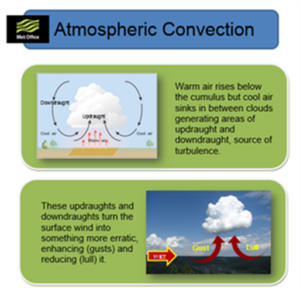

Anticyclones (high pressure) are normally associated with clear skies and good weather, so it is often assumed that there are no aviation hazards to be considered. However, the clear skies can allow overnight temperatures to fall and early / late radiation mist and fog can occur. Furthermore, the generally subsiding air beneath an anticyclone can trap pollution, smoke, dust and other microscopic solids to make the atmosphere particularly hazy. This can adversely affect visibility, particularly from the air to the ground (slant visibility). Finally, under clear skies the ground can heat quickly during the day and this can trigger convective processes leading to turbulence, gusty winds, sea breezes, spreading cloud, showers or even thunderstorms. Sinking air under high pressure does tend to suppress convection, but not always and usually not in the first few thousand feet – don’t get caught out!

So, what kind of hazards may be associated with convection?

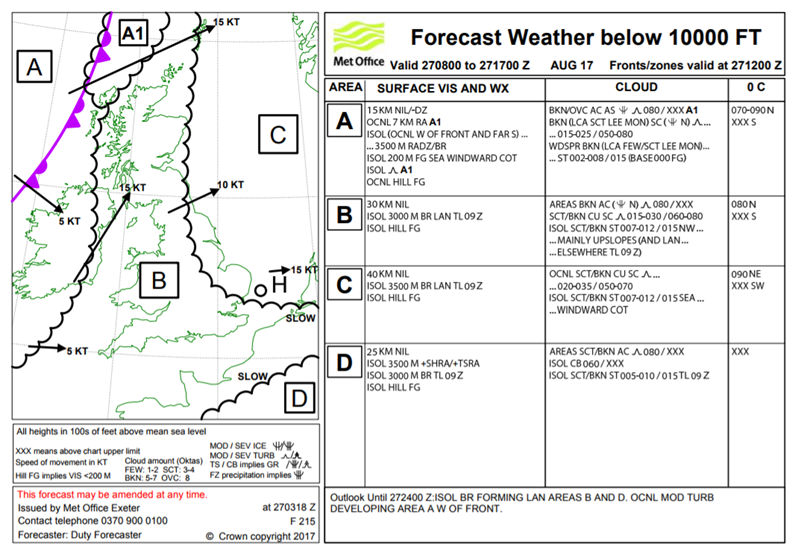

Area forecast

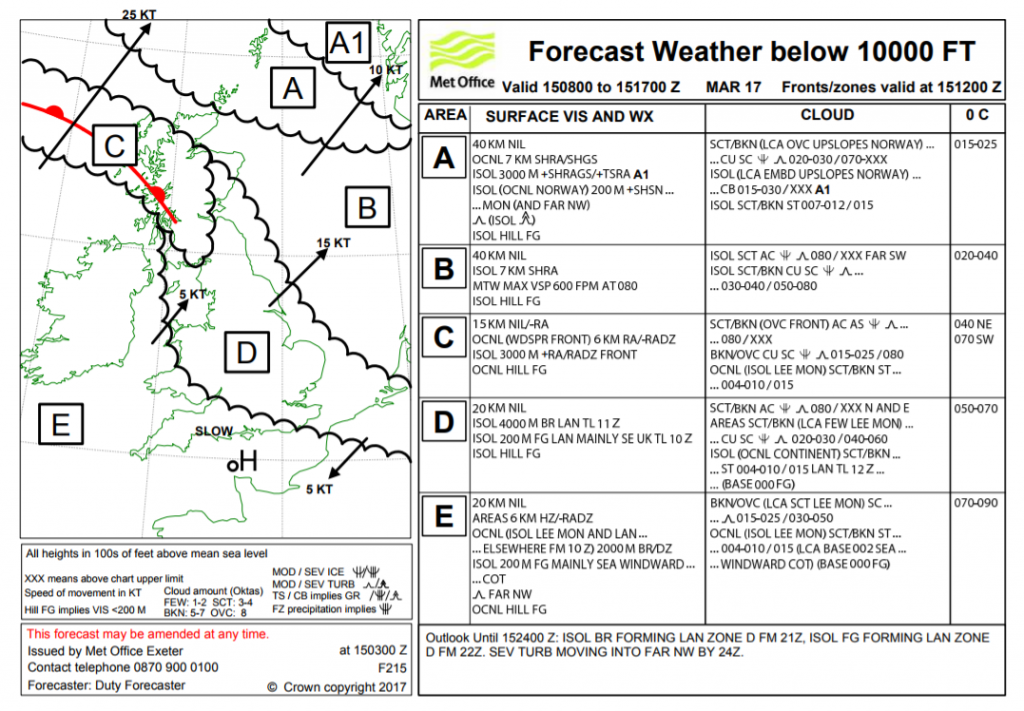

Looking at the F215 chart, is there anything along the route that I should be taking into consideration? What are the main cloud base and visibility? What is the altitude of the freezing level? Can I expect any fronts, weather, turbulence or icing?

For the flight from Southampton to Norwich I need to focus on areas B & C. Visibility is, generally, excellent but I may encounter patches of mist until 09Z. Hill fog may even be possible on windward slopes, with cloud as low as 500 feet.

There are extensive areas of cumulus and stratocumulus with a cloud base of around 1500-2000 feet. Considering the highest point of the Cotswolds is ~1100 feet, that doesn’t leave much of a gap. Additionally, areas of stratus are possible early in the planned flight period and near windward coasts. The freezing level is, thankfully, high at this time of year and should not be an issue and this is confirmed on the chart. The upper front on the synoptic chart appears to be no more than residual cloud, hence not precipitating nor reducing the visibility and with no significant turbulence.

Site specific information

Let’s have a look at the METARs/TAFs along the route, do they confirm the information contained in the F215? Have you checked possible diversion airfield(s) along your track as well as your destination? Are they suitable?

- METAR EGHI 270650Z 01005KT 330V040 CAVOK 15/12 Q1018=

- METAR EGLF 270650Z 31001KT CAVOK 15/14 Q1018=

- METAR EGUB 270650Z 34002KT CAVOK 15/13 Q1018 BLU=

- METAR COR EGLL 270650Z AUTO 04005KT 9999 NCD 17/11 Q1018 NOSIG=

- METAR EGGW 270650Z AUTO 02006KT 350V060 9999 NCD 14/11 Q1019=

- METAR EGSS 270650Z AUTO 36005KT 330V040 9999 NCD 15/11 Q1019=

- METAR EGSC 270650Z VRB01KT CAVOK 14/11 Q1019=

- METAR EGYM 270650Z AUTO 33003KT 9999 NCD 13/12 Q1018=

- METAR COR EGSH 270650Z 29004KT 250V320 CAVOK 15/12 Q1018 NOSIG=

- TAF EGHI 270625Z 2706/2715 VRB03KT 9999 FEW045=

- TAF EGSC 270659Z 2706/2715 35003KT CAVOK=

- TAF AMD EGSH 270557Z 2706/2715 VRB03KT 9999 FEW045=

The METARs are looking promising, most airfields reporting CAVOK (Cloud and Visibility OK), implying that the visibility is 10 KM or more, or NCD (No Cloud Detected). Some airfields are not yet opened but the few TAFs available indicate good conditions too. Based on these, it looks like the early visibility problems that are highlighted on the F215 have now cleared.

Threat & Error Management

ANTICIPATION: The weather seems fine – but what could go wrong to spoil your day?

- Visibility is already good at Southampton, but what about the surroundings in the event of an emergency in the early phases of flight?

- Can you fly your planned route in appropriate airspace when constrained by the terrain and forecast cloud? EGHI to EGSH involves some busy airspace with limited scope for manoeuvre.

- The surface visibility may be over 10 KM, but how far and how clearly can you see the ground in the cruise? Will it be far / clear enough to allow accurate navigation in busy airspace?

- How will variable wind (albeit light) affect your navigation?

- What is your plan for convection? Whilst it’s not specifically forecast for your area it can occur in these conditions in the first few thousand feet without generating cloud or weather (what glider pilots call “blue thermals”). Vertical motion and turbulence from convection may make it more difficult to maintain a constant height/altitude.

- If convective cloud, showers or even thunderstorms do develop unexpectedly what is your avoidance plan? (there are thunderstorms forecast across the English Channel in area D.

- Some METARS are showing 15 – 17°C at 0700 hours UTC. What is the maximum temperature for the day and how will it affect your aircraft’s performance?

RECOGNITION: A safe flight depends on being able to conduct safe VFR navigation and respond to unexpected hazards.

- Could you consider delaying departure for an hour or two to ensure clearance of mist / fog patches?

- With possibly limited air-to-ground visibility, do you intend making more regular navigation (gross error) checks and plan more regular waypoint checks?

- What is the variable wind doing to your track in relation to navigation & airspace limitations?

- Are you maintaining height/altitude accurately? Are you aware of vertical airspace limitations?

- If you need to avoid convective cloud or even showers, what are your plans for diversion, delay, extended fuel use etc?

RECOVERY: The potential combination of relatively poor visibility from the air and the development of apparently random convection / turbulence makes planning particularly difficult.

- Do you have diversion information for appropriate airfields along your planned track?

- Have diversion plans and clear go / no-go decision points for the flight. Be prepared to develop and adapt recovery plans as situations develop.

- What is your plan for becoming unsure of your position? When did you last practise with London Centre / D&D on VHF 121.5MHz?

- Ensure careful monitoring of fuel, distance, speed and elapsed time when dealing with delays (e.g. showers).

- During take-off and landing, be ready to deal with convective gusts and reduced performance due to high temperatures. Be ready to go around!

Summary

Anticyclonic conditions should mean a pleasant and straightforward flying day. Conditions for this flight are forecast to improve after a misty or foggy start and METARS suggest that this is already true. It’s looking good!

However, be aware that while winds may be light, they can also be variable, so monitor the impact on navigation and airspace avoidance. High pressure can trap haze in the lower atmosphere, affecting air-to-ground visibility. Higher ground temperatures can introduce hazards that are not explicitly forecast such as convection / thermals, associated turbulence, gusty ground winds and high-density altitude values. Don’t let fine weather cause complacency.

Finally – warm summer air can be surprisingly humid: beware carburettor icing.

Case 2: Tropical Maritime

Route: Cambridge to Gloucester (VFR) / Date: 11 March 2017, departing 0800 hours UTC

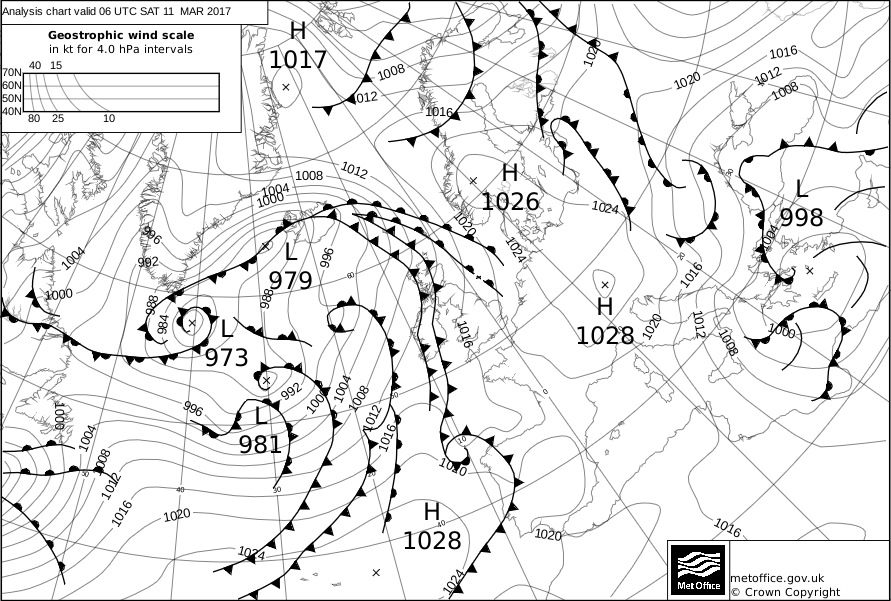

Synoptic situation

Describe the broad features in the synoptic chart, what is the main type of airmass covering the region and what kind of weather can we expect from it? How strong is the wind likely to be and what will its direction be?

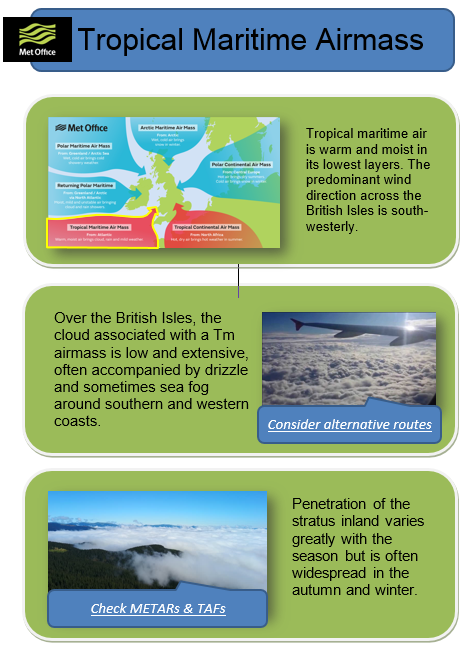

Most of the UK is covered by a south to south-westerly Tropical Maritime airstream. This airmass is mild and moist in its lowest layers, particularly over coastal areas and hills where it brings low clouds, drizzle and local hill fog. Judging from the number of isobars the gradient wind does not seem to be an issue but the complexity of the frontal system over the Atlantic indicates that conditions will deteriorate quickly and for quite a long time. The window of opportunity is brief and closing in!

So, what kind of hazards are usually associated with this airmass?

Area Forecast

Looking at the F215 chart, is there anything along the route that I should be taking into consideration? What are the main cloud base and visibility? What is the altitude of the freezing level? Can I expect any fronts, weather, turbulence or icing?

For the flight from Cambridge to Gloucester I need to focus on areas C & D where visibility may be reduced in haze, fog or hill fog and where the cloud base may be as low as 400 feet at times. The conditions are expected to improve but will deteriorate further to the west later: not a great forecast for VFR flight. The freezing level is above 8000 feet (AMSL) so there is no risk of icing at low level. Turbulence is expected along the route, but it is only slight. The possible restricted visibility means that you need to check the latest conditions at Gloucester (and the surrounding area) and make sure it will not be below minima for your arrival. In these conditions, it is simply not a good idea to “see how it looks when we get there”!

Site specific information

Let’s have a look at the METARs & TAFs along the route, do they confirm the information contained in the F215? Have you checked possible diversion airfield(s) along your track as well as your destination? Are they suitable?

- METAR EGSC 110650Z NIL=

- METAR EGGW 110650Z AUTO 16004KT 2900 BR OVC003 09/09 Q1018=

- METAR EGTK 110650Z 16005KT 2500 BR OVC005 10/10 Q1018=

- METAR EGVN 110650Z 17003KT 2000 BR OVC004 10/10 Q1018 YLO2 TEMPO 0600 FG BKN001 RED=

- METAR COR EGBB 110650Z 16006KT 4800 BR BKN007 10/10 Q1017=

- METAR EGBJ 110650Z NIL=

- TAF AMD EGBB 110712Z 1107/1206 17005KT 3000 BR BKN004

- BECMG 1107/1110 9999 NSW SCT010

- TEMPO 1110/1114 8000 BKN009

- PROB40 TEMPO 1201/1206 7000 RA BKN004=

- TAF EGVN 110741Z 1109/1209 17005KT 2500 BR BKN004

- BECMG 1109/1112 9999 NSW SCT018

- BECMG 1113/1115 FEW020

- BECMG 1200/1203 BKN012

- TEMPO 1201/1206 3000 RADZ SCT005=

The METARs are actually not very encouraging and indicate that the stratus is quite extensive. The TREND at Brize Norton also suggest a risk of fog during the next two hours. Cambridge and Gloucester airfields are not opened yet but there is no reason to believe that conditions will be any different there. Conditions described by the METARS confirm the information contained in the F215 chart but the TAFs indicate a potential improvement during the morning, with greater visibility and a higher cloud base.

Threat & Error Management

ANTICIPATION: Consider your limits and how the forecast cloud and visibility may present a threat:

- Is your departure and arrival time realistic given the forecast conditions at Cambridge and Gloucester?

- Can you fly your planned route in appropriate airspace when constrained by the terrain and forecast cloud?

- What is your safety altitude for the flight? Can you achieve this and remain VFR given the forecast?

RECOGNITION: A safe flight depends on conditions improving as forecast and not deteriorating faster than expected.

- As well as keeping a good lookout, what is your plan to get en-route METARS or other weather updates?

- How does this fit in with your wider communications plan?

- Where and when are your decision points on the route if conditions are doubtful?

RECOVERY: At each decision point you MUST have planned actions for the eventuality that the weather has not improved or is deteriorating further on your route. Given the forecast, it is likely that the best weather will always be behind you and away from exposed southern areas.

- Do you have diversion information for appropriate airfields to the north and east?

- Have you planned alternative routes to these diversions from each decision point?

Summary

The main concerns in this Tropical Maritime situation are low-level cloud and visibility along the route and possible deteriorating conditions on the approaching cold front. Conditions are forecast to improve after a misty or foggy start. The Brize Norton TAF is encouraging, but also note Birmingham’s best cloud conditions of scattered at 1000 feet. This is expected to increase and lower to become broken at 900 feet at times. This is probably due to the fact that Brize Norton is slightly protected in the Thames Valley while Birmingham (and, importantly, Gloucester) are more exposed to the Bristol Channel and Severn Valley. The movement of the cold front in the west will be key to conditions at Gloucester and this should be monitored carefully.

The flight should only be started once you are confident that en-route conditions are safe, and you should make regular checks on conditions at the destination before continuing past planned decision points. You must always have an alternate plan for deteriorating conditions AND PUT IT INTO ACTION AT THE FIRST SIGN OF DETERIORATION.

Case 3: Spring and Autumn

Route: East Midlands to Cambridge (VFR) / Date: 15th March 2017, departing 0800 hours UTC

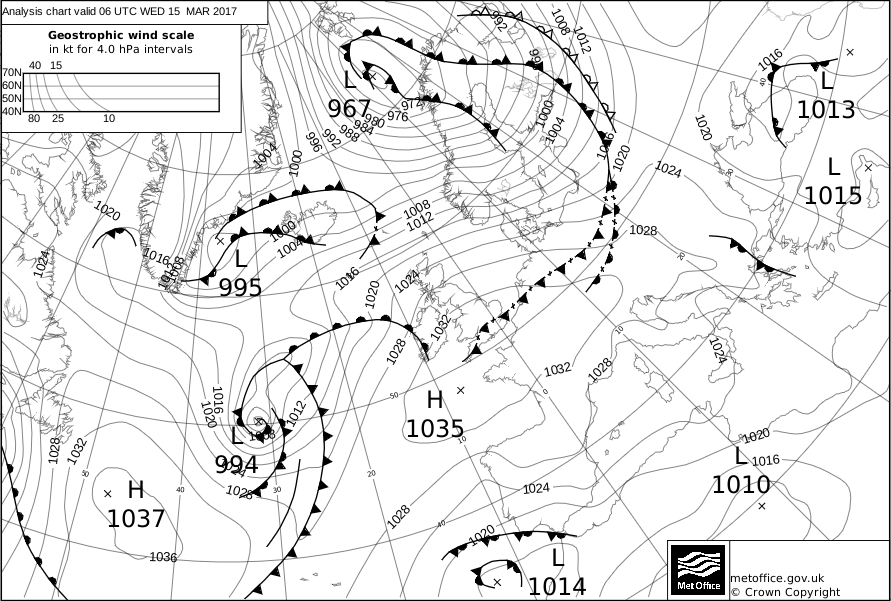

Synoptic situation

Describe the broad features in the synoptic chart, what is the main type of airmass covering the region and what kind of weather can we expect from it? How strong is the wind likely to be and what will its direction be?

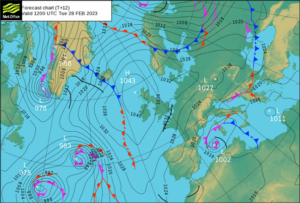

An anticyclone (1035hPa) extends a ridge over the south of the UK, suggesting settled conditions. A decaying cold front is slow-moving across southern England (the crosses on the front indicate that it is weakening). Despite becoming less active this front retains some of its characteristics. It is likely that significant amounts of cloud will be trapped under the ridge and this could be thick enough to generate rain and drizzle thus a risk of poor visibility in places.

The time of year is a key consideration for this forecast; it’s almost the March equinox so the length of day and night are nearly equal. The nights can still be cold and under such high pressure, it would not take long for fog to form in places. Additionally, away from the front and under any clear sky, the temperature can rise significantly and improve conditions during daytime.

So, what kind of hazards are usually associated with spring or autumn weather? Let’s have a look at the cheat sheet below.

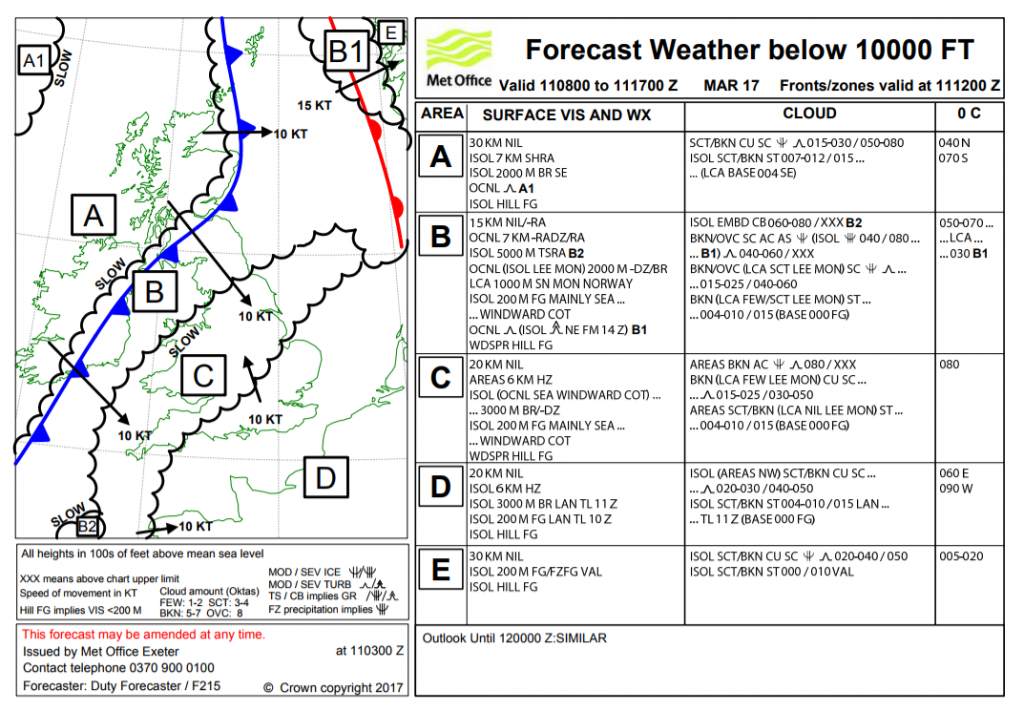

Area Forecast

Looking at the F215 chart, is there anything along the route that I should be taking into consideration? What are the main cloud base and visibility? What is the altitude of the freezing level? Can I expect any fronts, weather, turbulence or icing?

Focusing on the route from East Midlands to Cambridge and area D specifically, there seems to be a lot of cloud, all at various levels and accompanied by turbulence. Some moderate icing is expected but the lowest freezing level is expected to be 5000 feet. The main cloud base is expected to be quite low at around 2000-3000 feet but there will also be significant amounts (BKN) of stratus in some areas at very low level (400-1000 feet), which will persist until midday, so navigation may be challenging. The visibility does not seem to be badly affected by the anticyclone; there will be patches of fog, but these are expected to be isolated and mainly to the south-east of the UK. Although the medium level cloud (above 8000 feet) may not affect you directly, it will slow the process of heating the surface to clear mist and fog patches.

Site specific information

Let’s have a look at the METARs/TAFs along the route, do they confirm the information contained in the F215? Have you checked your destination airfield as well as the diversion(s) airfield(s), are they suitable?

- METAR EGNX 150650Z 22005KT CAVOK 06/05 Q1033=

- METAR EGBB 150650Z VRB03KT 9999 MIFG VCFG NSC 05/05 Q1033=

- METAR EGXT 150650Z AUTO 27008KT 4600 BR SCT150/// 06/05 Q1032=

- METAR EGGW 150650Z AUTO 30003KT 0150 R26/0275 FG VV/// 06/06 Q1033=

- METAR EGSC 150650Z NIL=

- METAR EGSS 150650Z 32003KT 2500 R22/0400 BCFG NSC 05/05 Q1033=

- METAR EGYM 150650Z 23004KT CAVOK 08/07 Q1033 BLU NOSIG=

- TAF EGNX 150503Z 1506/1606 24006KT 9999 SCT030

- PROB30 TEMPO 1506/1509 8000

- BECMG 1602/1605 BKN007

- TEMPO 1602/1606 2000 BR BKN002=

- TAF EGGW 150500Z 1506/1606 28007KT 3000 BR FEW020

- TEMPO 1506/1509 0300 FG BKN001 BECMG 1509/1512 9999 NSW

- PROB30 TEMPO 1509/1512 BKN008 TEMPO 1520/1606 3000 BR

- PROB30 TEMPO 1523/1606 0800 FG BKN001 BECMG 1603/1606 22010KT=

- TAF EGYM 150740Z 1509/1518 24008KT 9999 SCT025=

A few airfields are reporting visibility problems as previously discussed with the synoptic chart analysis but these are not expected to last past 1100 hours UTC. Cambridge airfield is not yet opened but, looking in the vicinity, both Luton and Stanstead are reporting fog or fog patches. Marham is CAVOK (Ceiling and Visibility OK) with a NOSIG (No Significant changes) trend. Of note, Luton (EGGW) is expecting temporary spells of broken cloud at 800ft until midday. This all agrees with the F215 chart regarding the forecast cloud and the fog patches being mainly in the southeast of the UK.

Threat & Error Management

ANTICIPATION: Consider your limits and how the forecast cloud and visibility may present a threat:

- Is your departure and arrival time realistic given the forecast conditions at East Midlands and Cambridge and the possibility of low cloud along the route?

- Can you fly your planned route in appropriate airspace when constrained by the terrain and forecast cloud and visibility? Remember those low cloud patches!

- What is your safety altitude for the flight? Can you achieve this and remain VMC, below the freezing level given the forecast?

RECOGNITION: A safe flight depends on conditions improving as forecast and cloud.

- What is your plan to get up to date METARS or other weather information? Online? Phone ahead before departure? Web cams?

- Can you check destination conditions en-route? How does this fit in with your wider communications plan?

- Where and when are your decision points on the route if conditions become unsuitable to continue?

RECOVERY: At each decision point you MUST have planned actions for the eventuality that the weather does not improve or is unsuitable on your route. Given the forecast, it is likely that the best weather will always be behind you and away from the southeast.

- Can you delay departure until you are certain that conditions are suitable along your entire route?

- Do you have diversion information for appropriate airfields away from the greatest fog / mist and low cloud risk?

- Have you planned alternative routes to these diversions from each decision point?

Summary

The main concern in this spring high pressure situation is how quickly the early mist/fog will clear and the variability of low cloud from the weakening cold front. Having analysed the situation, it seems the worst of the conditions are located to the south-east of the UK and may persist until midday. Cloud base is set to be around 2000 – 3000 feet with visibility greater than 10KM (after 09Z). However, the anticyclone is likely to trap low level moisture and there is a risk of low-level cloud until midday. Do you really have to go at 0800 hoursUTC? Consider the duration of your flight, weather improvement times and the length of remaining daylight and good conditions.

The flight should only be started once you are confident that en-route conditions are safe and you should make regular checks on conditions at the destination before continuing past planned decision points. You must always have an alternate plan for unsuitable conditions AND PUT IT INTO ACTION AT THE FIRST SIGN OF DETERIORATION.

Case 4: High pressure – Winter flight

Route: Lydd to Oxford (VFR) / Date: 28 February 2023, departing 0900 hours UTC

Synoptic situation

What are the broad features in the synoptic chart, what is the main type of airmass covering the region and what kind of weather can we expect from it? How strong is the wind likely to be and what will its direction be?

In this case study the UK is dominated by an anticyclone centred over northern Scotland. Anticyclones normally bring settled weather, however the seasons and origin of the airmass often result in differences in cloud cover. For example, whilst we associate high pressure as bringing fine sunny weather to the UK during the summer, the same high pressure can lead to extensive cloud cover at other times of the year – what is commonly known as ‘Anticyclonic gloom’. The incidence of cloud cover ‘trapped’ under an anticyclone can have a significant impact on air temperatures, especially under a clear high pressure during winter months. This combined with light winds and moist ground can increase the potential for fog to form.

Wind flow is clockwise around an anticyclone, so in this example southern England is influenced by a NE’ly airflow. The synoptic chart also highlights a trough line running along the English Channel, likely to be the result of the airmass being modified by its passage over the relatively warm water of the English Channel. Troughs are indicative of lines of convection, often producing showers. What impacts might convective activity have over Kent as we prepare our flight

So whilst anticyclones are associated with generally fine flying conditions, the seasons, origin of the airmass will all have an impact on the weather. In winter, consider the potential for low temperatures (and, consequently, a low freezing level), areas of fog, cloud cover and the direction of wind flow.

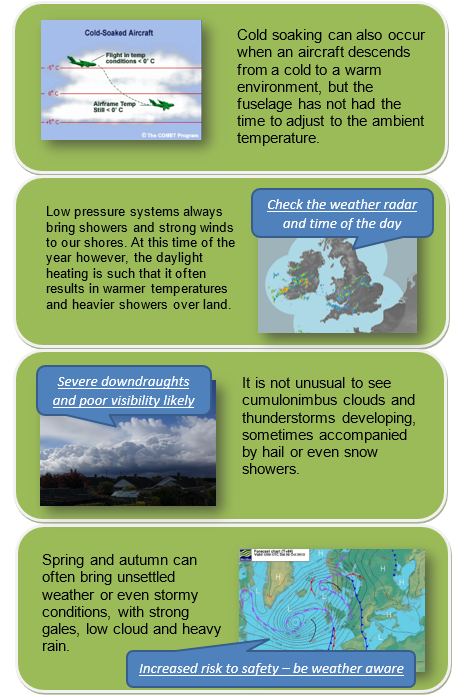

Consider also the potential for locally induced convective activity over relatively warm surfaces and as the day warms, which may result in downdraughts, turbulence, reduced visibility, airframe icing and frozen precipitation, as summarised below.

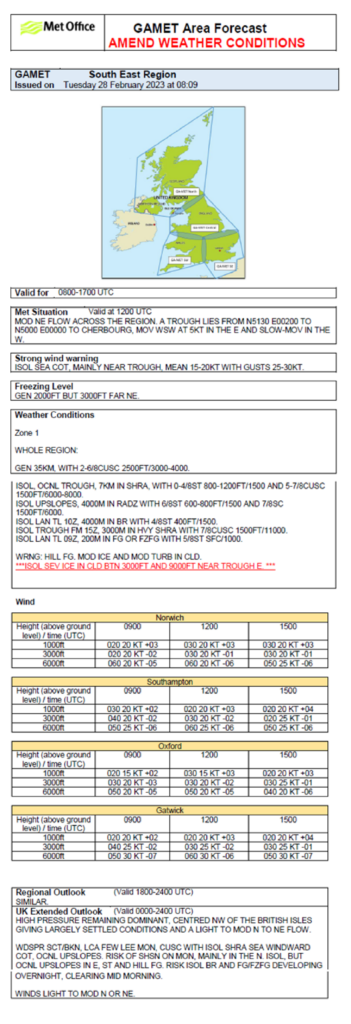

Area forecast

In this case study we will consider the GAMET area forecast for the SE of the UK, valid for the period 0800-1700 UTC. The flight from Lydd to Oxford exists entirely within the area bounded by the SE GAMET, so this area forecast should be our focus. Looking at the GAMET, is there anything along the route that we should be taking into consideration? What is the main cloud base and visibility? What is the altitude of the freezing level? Can we expect any weather, turbulence or icing?

In general we can expect good visibility throughout our flight, with areas of cloud with a base of 2500ft. The tops of these clouds are 4000-4000ft, so fairly shallow. The highest point over the South Downs is 900ft and 1000ft over the Cotswolds. Area forecast references to cloud are referenced to mean sea level, so over these areas of high ground, the cloud base will only be about 1500ft.

A concern is the presence of the slow moving trough line, which is very close to our departure airport, Lydd. Close to the trough the GAMET highlights a chance of showers. In any showery activity we can expect the cloud base to lower to 800ft and the surface visibility to reduce to 7km.

Other possible hazards include a small risk of rain or drizzle on upslopes that face the direction of the wind flow. These may reduce the cloud base to 600ft and the visibility to 4000m. Over high ground this will mean cloud on the surface, so we should not discount the potential for localised areas of mist or fog, resulting from cloud lowering to the surface.

In areas of cloud we can expect the potential for icing and turbulence (which may be severe close to the trough). We should therefore definitely avoid entering areas of cloud cover.

Spot wind and temperatures are available for Gatwick, which is along our intended route, and for Oxford (our intended destination). At our flying altitude we can expect a NE’ly wind at 20KT, and outside air temperature below zero. The freezing level section of the forecast confirms the zero degree isotherm at 2000ft.

There is a strong wind warning in effect for coastal areas and close to the trough. Lydd is both coastal and near to the trough. Lydd’s runway is aligned 03-21, so thankfully cross wind on take-off should not be an issue. However, beware of gusts to 30kts.

Site specific information

Let’s have a look at the METARs/TAFs along the route, do they confirm the information contained in the GAMET? Have we checked possible diversion airfield(s) along the track as well as our destination? Are they suitable?

METAR EGMD 280820Z 02010KT 9999 VCSH SCT014 BKN019 BKN024 05/03 Q1032=

METAR EGKK 280820Z 01008KT 340V040 9999 SCT018 03/01 Q1033=

METAR EGKB 280820Z 35007KT 9999 BKN017 02/01 Q1033=

METAR COR EGLL 280820Z AUTO 01004KT 340V040 9999 NCD 03/01 Q1034 NOSIG=

METAR EGUB 280820Z 00000KT 7000 3000NE BR FEW003 OVC017 M00/M00 Q1034 TEMPO 7000 BR RMK YLO1 TEMPO WHT=

METAR EGTK 280820Z 01006KT 9999 VCSH SCT012 BKN017 04/03 Q1034=

TAF EGMD 280757Z 2809/2818 02009KT 9999 FEW015 SCT025 PROB40 TEMPO 2809/2818 03015G25KT 7000 SHRA BKN008=

TAF EGKK 280458Z 2806/0112 02008KT 9999 SCT035 PROB30 TEMPO 2806/2810 BKN009 PROB30 TEMPO 2816/2823 7000 SHRA BKN014=

TAF EGKB 280757Z 2809/2818 01007KT 9999 FEW005 SCT030 PROB30 TEMPO 2809/2810 7000 BKN005 PROB30 TEMPO 2810/2812 BKN010=

TAF EGLL 280459Z 2806/0112 02009KT 9999 FEW045 PROB30 TEMPO 2806/2809 BKN007 PROB30 TEMPO 2809/2811 BKN014 PROB30 TEMPO 2812/2822 8000 SHRA BKN014=

TAF EGUB 280755Z 2809/2818 VRB02KT 6000 BR BKN020 PROB30 TEMPO 2809/2813 SCT012 BECMG 2810/2813 9999 NSW BKN025 TEMPO 2813/2818 BKN020 PROB30 TEMPO 2817/2818 SCT014=

TAF EGTK 280757Z 2809/2818 02008KT 9999 FEW015 SCT025 PROB40 TEMPO 2809/2812 BKN012 PROB30 TEMPO 2815/2818 8000 SHRA=

The METARs prior to take-off are looking fairly promising with good visibility (9999) and variable amounts of cloud at about 2000ft (remember, the cloud base in METARs and TAFs are referenced to ground level, not mean sea level). However there is a shower reported close to Lydd and Oxford (VCSH), and patchy low cloud at Benson (FEW003). The cold surface temperatures confirm the risk of carburettor and/or airframe icing in any cloud.

The TAFs along the route are consistently highlighting a probability (PROB30 or PROB40) of lower cloud during the morning. A good clue is the closeness of the air temperature and dew point values in the METARs, the closer they are the greater the risk of low cloud and /or poor visibility – the risk of fog is low, but not zero (remember, TAFs will omit weather conditions that are considered to be less than 30%).

Threat & Error Management

ANTICIPATION: Consider you limits and how the forecast cloud, visibility and weather hazards may present a threat. Lydd to Oxford is a fairly long flight so pilots need to have determined their own personal minima, and then compare that to the worst of the forecast weather enroute and the availability of nearby good weather options to get down safely.

- Cloud base and visibility values provided in any aviation forecast should be regarded as the most likely values, however be aware of the potential for lower than forecast cloud and/or visibility along the route.

- Visibility and cloud base is generally suitable for the flight, but here remains a risk of low cloud and/or visibility. What will we do in the event that encounter such conditions?

- Our planned route takes us over the relatively high ground of the South Downs and Cotswolds. Will we have sufficient cloud base to fly at a Minimum Safe Altitude and avoid icing conditions?’ (remembering that cloud base detail in area forecasts are referenced to mean sea level, not ground level). An IMC/IR rated pilot would face the fact that, on going IMC, the rules say that you must fly at Minimum Safe Altitude (MSA), which is terrain elevation +300’ for unmapped obstacles +1,000’ safe clearance – this puts us into the ‘icing zone’ due to the low freezing level.

- What is our plan in the event that we encounter convection. Yes, the risk is forecast to be low, but it is not non-existent. In such an eventuality, we may encounter icing and turbulence, how do we intend to plan to avoid this situation?

- Have we checked the latest forecast just before our flight? The GAMET used in this case study has been amended from the original forecast issued (in this case to draw awareness to an increased risk of severe icing in cloud close to the trough).

- The risk of encountering low cloud and reduced surface visibility reduces during the afternoon. Might we consider delaying our flight for a couple of hours?

RECOGNITION: A safe flight depends on being able to conduct safe VFR navigation and respond to unexpected hazards.

- A big threat is sudden inadvertent IMC due to a low and fluctuating cloud base. This is a big cause of ‘loss of control’ and ‘controlled flight into terrain’ for non-instrument pilots. Do we have a plan to mitigate this threat?

- If we need to avoid low cloud en-route, what are our plans for diversion, delay, extended fuel use etc?

- Are we maintaining height/altitude accurately? Are we aware of vertical airspace limitations?

- If we find ourselves in cloud and are starting to detect ice accretion, what are our plans for manoeuvring out of the cloud and to de-ice?

RECOVERY: The potential for relatively low cloud and the possibility of convective showers makes planning for these eventualities important. South-east England is a very busy environment where nav and comms workloads tend to be very high, so bad weather could easily lead to overload. The stress of bad weather would just add to that.

- Do we have diversion information for appropriate airfields along our planned track?

- Have diversion plans and clear go / no-go decision points for the flight. Be prepared to develop and adapt recovery plans as situations develop.

- What is our plan for becoming unsure of our position if we inadvertently find ourselves in cloud? When did we last practise with London Centre / D&D on VHF 121.5MHz?

- Ensure careful monitoring of fuel, distance, speed and elapsed time when dealing with delays from encountered weather.

- During take-off for this flight, be ready to deal with gusts by changing your airspeed by up to 10KTs

Summary

Anticyclonic conditions normally provide settled weather. In this case the settled weather takes form of patchy cloud and good visibility along the route. This confidence is somewhat tempered by the potential for areas of cloud to lower close to, or onto, the surface, along upwind slopes of high ground. The other factor is the chance of convective activity, including showers, particularly close to the departure point.

Hazards to be aware of, and to plan for, therefore include:

- inadvertent IFR;

- icing, turbulence;

- showers enroute; and

- gustiness at take-off

Pre-planning

Check paperwork before the flight, especially following a long delay, to ensure that the flight is legal. This can include:

- PPL A: Valid Class Rating (ratings page) and hour requirements

- LAPL: Hours “Rolling Validity” and hour requirements

- Medical/PMD Combination valid for type of aircraft being flown

- Valid Aircraft Insurance that covers the pilot for planned flight

- Valid CofA ARC or Permit to Fly

- Part 21 Journey Log: – no defects or defects noted

- Carriage of documents relevant for aircraft type (LAA Permit to Fly or Part 21)

Planning checklist

Checklists can help avoid overlooking important matters to ensure that all aspects of planning have been covered. This should include:

- Weather (as discussed in the Met paper at [link])

- NOTAMs

- Flight plans, including

- Moving map and charts up to date

- Airfield opening times

- PPR and how to depart from and arrive to your aerodromes in accordance with their published procedures.

- Terrain

- Airspace en-route

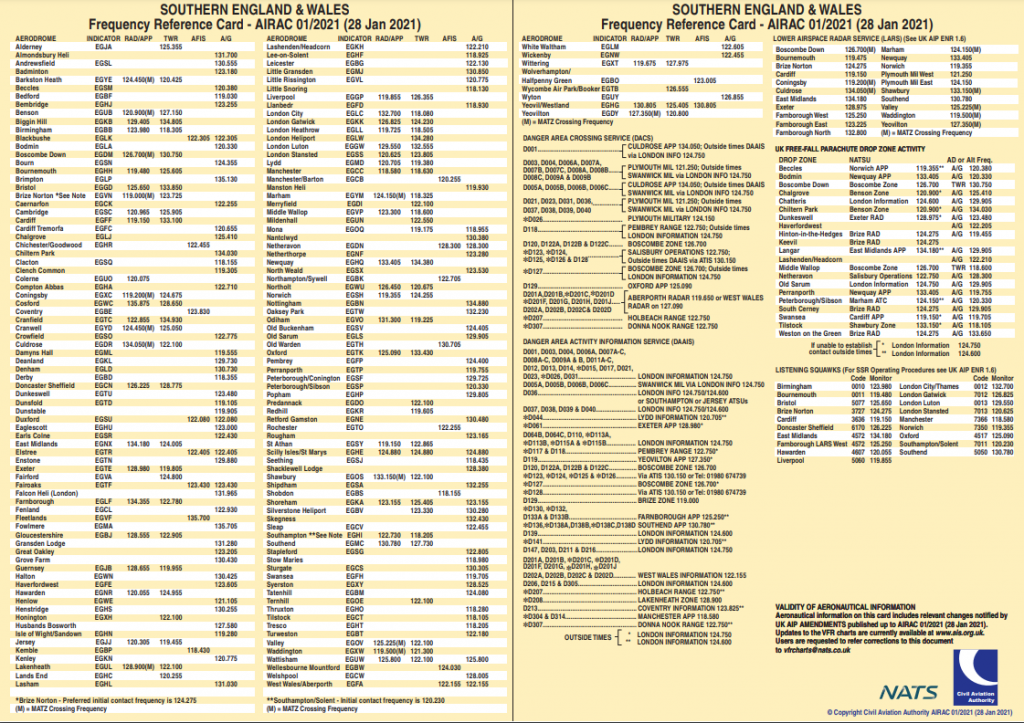

- Frequency Monitoring Codes (FMC) and associated frequencies. A separate section explains how to use FMC. The latest Frequency Reference Cards (see Figure 1) are available from the NATS AIS site in printable format and updated at AIRAC Cycle.

- Planning for alternate aerodromes en-route

- Fuel – including for possible diversion

- Weight and balance. CAP2097 issued in February 2021 offers some good advice about weight and balance.

Before flying, ask yourself if you are current and if you are fit to fly. You may wish to use a checklist such as IMSAFE (Illness, Medication, Stress, Alcohol, Fatigue and Emotion).

When planning you may wish to make full use of the following resources:

- Check http://skywise.caa.co.uk/ for the latest alerts and advice from the CAA

- Check https://airspacesafety.com/ for infringement updates and guidance

- Check https://www.nats.aero/do-it-online/ais/ for AIPs and supplements

Use of charts

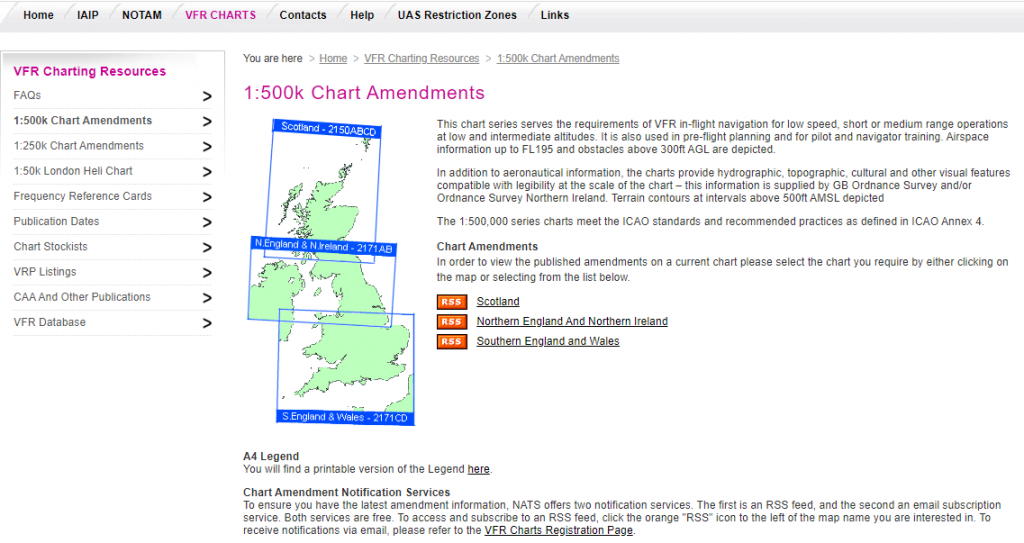

Make sure your chart is up to date but remember that even the latest chart may not include all changes to airspace along your route. A comprehensive guide to VFR chart resources is found at the NATS AIS website (here) and is available free to all users. Currently the following VFR resources are available:

- Full list of amendments to all current VFR charts

- An email notification service detailing the latest amendments to all current VFR charts

- VFR chart scheduled publication dates

- VFR chart stockists

Prior to planning a route, check the relevant chart amendment by navigating through the page in Figure 2:

The legend at the bottom of the chart contains the information needed to use the chart effectively.

Use of GPS

- Learn to use it on the ground. This will help reduce mistakes in the air, avoid loss of situational awareness and prevent your eyes being in the cockpit for too long.

- Make sure the moving map is configured to show airspace above the planned route as it may be ‘hidden’.

- Do not simply draw a line between departure and destination aerodromes: mark out legs/waypoints and check along each to make sure there is no controlled airspace (including vertical airspace), danger area, restricted area or ATZ along the path. For each of the airspace structures along the route, either plan to communicate with the airspace operating authority to obtain a clearance and necessary information to enter; or plan to Take 2 around the outside/underneath.

- If possible, print off a PLOG. This will provide a backup should the GPS fail for any reason. It will also provide en-route frequencies for e.g. aerodromes and LARS units.

- If weather and NOTAM information is provided on the moving map/software, make sure they apply to the actual day and time of flight rather than the day before when the plan was made.

- For up to date information on specific NOTAMs, including Restricted Areas (Temporary), Airspace Upgrades and Emergency Restrictions of Flying, call the AIS Information Line on 08085 354802 or +44 (0)1489 887515

- Be cautious about using the ‘direct to’ function during flight as the resulting track may take you through [designated] airspace. Check the route carefully before following the line.

- Make sure alerting is switched on and you understand the range of alerts available, for example, the advance warning when approaching controlled airspace. But be aware of ‘alarm fatigue’, particularly if you fly in areas of complex airspace. Many pilots receive many alerts and as a result turn them off without focusing on them ‘because they already know they are near controlled airspace’.

- Plan on which QNH you are going to use for each leg, preferably the QNH of the airport that operates the controlled airspace.

- If your airfield uses QFE remember to change to QNH immediately after take-off. Never fly cross-country using QFE and avoid RPS as it increases the risk of infringing.

Threat and Error Management

As you plan the flight use the Threat and Error Management to alert you to issues you may have overlooked.

Plan for maximum safe altitude (the lower limit of vertical controlled airspace less 200 feet if possible) for each leg alongside minimum safe altitude, perhaps alongside the MSA calculation:

| Safe altitude | |

| minimum | maximum |

Distraction

Plan for distraction. If you are following your plan and become distracted by anything – such as a sick passenger or difficulties on the radio – positively identify that as a distraction and bring your mind back to what you were doing before the distraction occurred:

Think –

- What was I doing before the event?

- At what point was I interrupted?

- How do I get back to where I was?

Distractions often lead to error and can occur at any stage of the flight, and indeed pre-flight if other things are on your mind, from the walk round to securing the aircraft.

To many, the term Threat and Error Management, or TEM, suggests a complex activity which is a bit on the heavy side for recreational aviation.

Don’t be put off by terminology. TEM, Risk Assessment and to a degree airmanship have a lot in common. In everyday life we practice TEM and Risk Assessment and use the result to avoid loss or injury; in aviation the same applies.

Threats

A threat is an event or error that occurs beyond the influence of the flight crew, increase operational complexity, and which must be managed to maintain the margins of safety. If the threat is left unmanaged, it could lead to an unsafe condition, such as injury or loss, or in aviation what can be described as the aircraft not following the plan or, to use another term, being in an Undesired Aircraft State (UAS). Again terminology, but for example if the aircraft enters controlled airspace by error then it is said to be in an UAS.

Threat management is effectively reviewing your planned flight and looking for where or when factors can threaten the successful outcome. We use TEM in everyday life. You will already be using it in your flying, but as we know from statistics some flights have not well managed the threat, and as a result injury, loss or an UAS has occurred.

Errors

Errors result from actions or inactions by the crew. We all make mistakes some of which have no adverse effect; some, however, have significant effects. Avoiding errors starts with looking for threats and, once identified, putting mitigation measures in place. However, it is also important to recognise and correct errors if they do occur.

Management

An example of how threat management might avoid an error is in the use of a check list. Avoiding the consequences of a wrongly sequenced engine start-up can be assisted by the use of a check list, which if followed cannot result in anything other than the correct sequence. Of course, humans being humans may sometimes decide that they don’t need the checklist and as a result might miss a vital part of the sequence; or they might use the list but still miss part of the sequence in error.

If, for example, in this instance the aircraft was started at full throttle, it might runaway causing damage and injury. What would you do at this point? The obvious thing to do as you sit reading this is to close the throttle and shut down the engine. However, in real life some pilots have only tried to hold the aircraft on the brakes to no avail and crashed into something on the ground; one actually attempted to take-off from the apron only to find that control locks were still in place and a very short fight and crash ensued. Error management in this case would have planned for the potential, engines do odd things at times, and have been ready to close the throttle, shut down the engine and manage the error.

Planning to fly

When it comes to planning a flight an attentive pilot should bring TEM into not just the aircraft preparation, daily inspection, fuel sufficient with a reserve, air in the tyres and themselves, IMSAFE for example, but also threats that could occur during the flight. For example, having decided where you want to go you will of course review the weather for your route and destination. Why? Because although the sky is clear at the home base your destination is 50 miles away and close to the coast and the weather there can be very different. So:

Threat – Potential Weather. Management – Obtain a report and forecast.

Your route takes you close to some quite complex airspace which you intend to remain clear of. You are using a VFR moving map, with a paper chart marked as a reserve (good TEM if the moving map lost its signal or the battery gave up), which will help keep you clear of airspace as long as everything goes OK! However there is always the risk that even with the best of intentions you may just wander off the magenta line and so you allow a little extra margin by moving your line at least 2 NM from a horizontal boundary were you can.

The Threat – Not absolutely spot on with the planned route could lead to an infringement. Management – Plan a sensible margin.

Having drawn a line, you check for any airspace above or below your route because you plan to avoid it and similarly to the 2 NM buffer you gave the side of airspace you plan a 200 feet buffer when flying below or above.

Threat – Infringing airspace. Management – Identifying limits and planning to avoid.

Passengers

Studies of several hundred infringements have shown that a significant cause of infringements is distraction. A pilot can be distracted in many ways, but a significant number of distractions have been linked in one way or another with passengers. Delightful though it is to share your flying enjoyment with a passenger, they can also weaken your attention, possibly just when you need all of it to conduct the flight safely. Treat your passenger as a potential hazard and seek mitigation. There are legal requirements for passenger briefings, and it is important that you cover potential passenger threat within the briefing. For example, “During the preparation, taxi, take-off and initial climb please don’t talk to me unless it is an emergency.” So:

Threat – Distraction by Passenger. Management – Prepare and Brief Passenger.

There are times when a passenger can be of assistance. Mid-air Collision (MAC), is always a threat. You can mitigate by using an electronic conspicuity device, talking to an air traffic service unit and receiving a Traffic Service, and of course lookout. With a passenger in the cockpit there is a second pair of eyes and you can add these to your own lookout, with a short briefing, to assist to manage the threat.

Threat – MAC, Management – Ask passenger to assist with lookout.

Route planning to avoid an infringement

The CAA’s Avoiding airspace infringements card is designed to prompt thought when planning and executing a flight so that as a pilot you have made a positive plan to avoid an airspace infringement. That may sound pretty obvious, but the key to avoiding an infringement is to positively plan not to have and infringement. This means looking at your route and seeing where there is potential for an infringement, the threat, and planning how you will avoid the infringement, the management.

Let’s look at a practical example of planning not to infringe. You plan to fly from City Airport, Manchester (Barton) near Manchester, to Sywell, near Northampton. First get your chart out, make sure it is up to date, (that’s another threat that you have avoided) and look at the route and see where an infringement is more likely to happen unless you plan to avoid it.

There are several such areas. The Manchester Low level Route (LLR) is the first. The most obvious avoid is flying too high when travelling within the LLR. The less obvious, and from the actual infringement reports the most likely to happen, is not descending from a higher cruise level early enough and flying through the base of the airspace above the entrance of the LLR. The other error, although not as common, is starting to climb too early and flying through the base of the airspace on the way out. So, the plan should include a fixed waypoint before the entry by which the level that you fly through the LLR must be established, and a point at the other end where you know that you are clear and safe to climb. Don’t forget that the base of the airspace over the LLR is based on the Manchester QNH, so you must have the altimeter set correctly before you reach the entry waypoint.

Having left the LLR you will want to climb from the abnormally low level. The threat here is that the Manchester CTA immediately south of the LLR has a base of just 2,500 feet and it won’t take long for most aircraft to reach that level. Make sure that you have a plan that will keep you below the CTA with a margin for error. Remember the ‘Take 2’ initiative? Where possible stay 2NM horizontally from the edge of controlled airspace and 200 feet below the base when underneath. So, in this case set an initial climb limit of 2,300 feet. And the easiest way to remember it is to write it down clearly on your log.

Threat – Overshooting your planned height. Management – writing it down on your PLOG.

Having flown past Crewe, the bases of controlled airspace for the rest of the way to Sywell don’t go below 4,500 feet so, given usual cruising levels, vertical infringement shouldn’t be an issue? But do make sure that you have noted an upper limit for your flights, say 4,300 feet on your PLOG just in case you get tempted to fly higher at some point. It’s easy to miss some of the annotations on the chart in-flight, particularly if it’s a bit bumpy and there are other things to do.

Threat – climbing into airspace, Management – writing an upper limit on your PLOG.

It is possible to infringe an Aerodrome Traffic Zone (ATZ). You will note that along the way your route passes close to the Tatenhill ATZ. This is a threat to manage. The upper limit is at 2,450 feet above mean sea level. You could fly over it, or around it. Have a plan before you take-off, and just in case note the frequency of Tatenhill so that if you need to call you can and avoid an infringement or alternatively just to maintain a listening watch for spatial awareness. Remember to be ultra-careful close to an ATZ, the highest rates of potential mid-air collision are in the vicinity of aerodromes, maintain a very good lockout.

Threat 1 – Needing to enter the ATZ. Management – preparing communication details as part of the PLOG.

Threat 2- greater chance of MAC. Management – monitoring the radio for local traffic and enhanced lookout.

However, you choose to route you must stay out of the ATZ unless following the requirements for ATZ entry which are published in Rule 11 of The Rules of the Air Regulations 2015. A brief summary is as follows:

- An aircraft must not fly, take off or land within the ATZ of an aerodrome unless the commander of the aircraft has complied with paragraphs 2, 3 or 4 as appropriate.

- If the aerodrome has an air traffic control unit, the commander must obtain the permission of that unit to enable the flight to be conducted safely within the ATZ.

- If the aerodrome provides flight information service, the commander must obtain information from the flight information centre to enable the flight to be conducted safely within the ATZ.

- If there is no flight information centre at the aerodrome the commander must obtain information from the air/ground communication service to enable the flight to be conducted safely within the ATZ.

In addition, the commander of an aircraft flying within the ATZ of an aerodrome must —

- cause a continuous watch to be maintained on the appropriate radio frequency notified for communications at the aerodrome; or

- if this is not possible, cause a watch to be kept for such instructions as may be issued by visual means; and