Infringement of the Class D Farnborough Control Area 1 (CTA-1)

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing SEP |

| Type of Flight | Cross Country Recreational |

| Airspace/Class | Farnborough CTA / Class D |

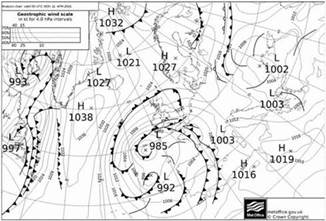

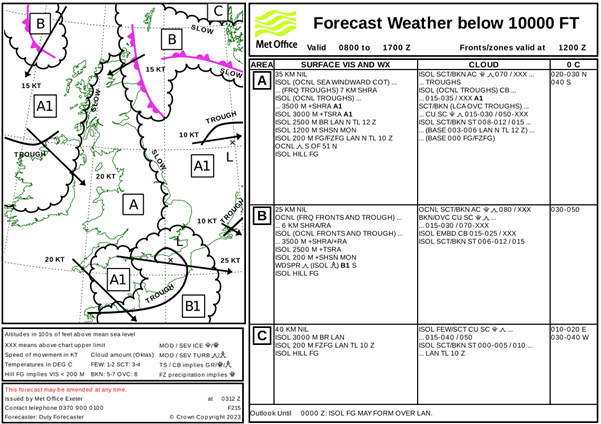

Met Information

METAR EGLF Z XX1020Z 04013G24KT 360V060 9999 SCT022 06/M01 Q1025

METAR EGLF XX1050Z 06014KT 9999 SCT026 06/M01 Q1025

Air Traffic Control

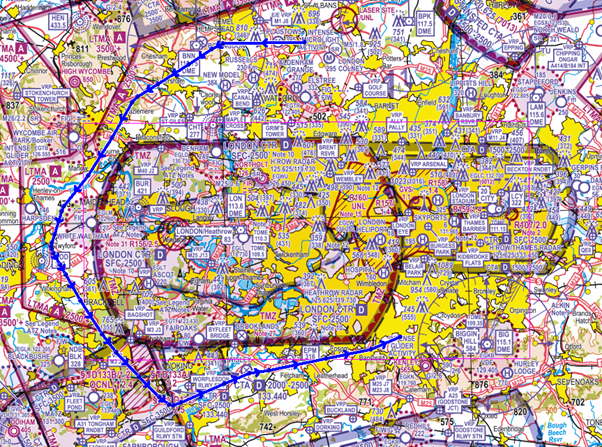

The Air Traffic Controller reported operating as Farnborough West and Farnborough Zone band-boxed in busy traffic. The aircraft had been handed over from Farnborough LARS North requesting a Farnborough controlled airspace transit. The aircraft was asked to squawk Mode A 0460 (for Zone) and placed under a Basic Service. A transit clearance was issued routing Southwest of the Bagshot Mast to the Ockham VOR/DME (OCK), not above altitude 2,000 feet, VFR, remaining outside the London Control Zone (CTR). This was read back correctly after being challenged for an omission from the clearance in the initial read back.

Whilst monitoring the track of the aircraft, the service was changed from a Basic Service to a Radar Control Service as the aircraft entered LF CTR-1 southwest of the Bagshot Mast and then back to a Basic Service as the aircraft vacated the Farnborough CTR-2 in the vicinity of Woking. The aircraft requested to route via OCK after leaving Farnborough CTR-2 and was advised that they could resume their own navigation.

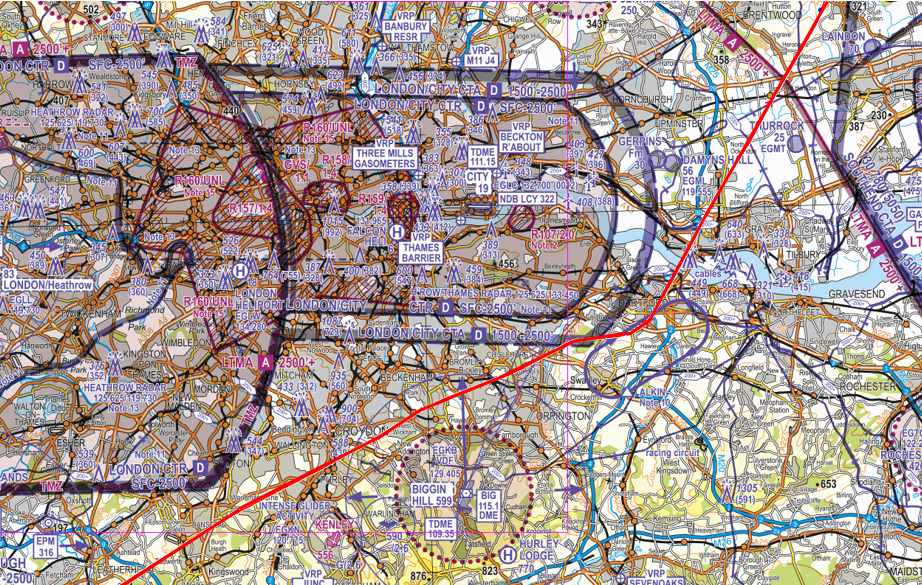

Whilst the aircraft was maintaining 1,900 feet beneath CTA-1 (base of 2,000 feet AMSL), the controller instructed the pilot to reset squawk 0435 (for LARS). The controller was imminently to issue advice that the aircraft was operating at the base of controlled airspace, as the aircraft’s altitude was observed to climb to 2,100 feet, which triggered an Airspace Infringement Warning (AIW) alert. The controller informed the pilot that they had entered controlled airspace and instructed them to descend to be not above 2,000 feet to remain outside. The pilot apologised and the aircraft was then observed to descend to leave controlled airspace.

Note: The Ockham VOR is no longer certified for en-route navigation. While its DME has a designated operational coverage (DOC) of 70NM, the VOR component is retained solely for terminal and approach procedures at select airports, including Heathrow.

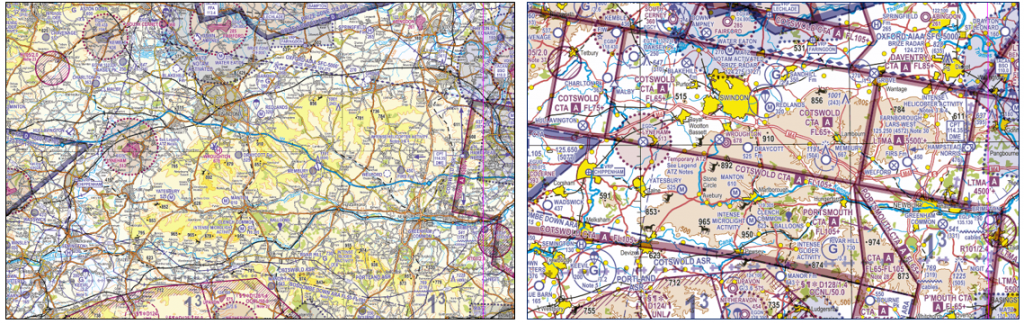

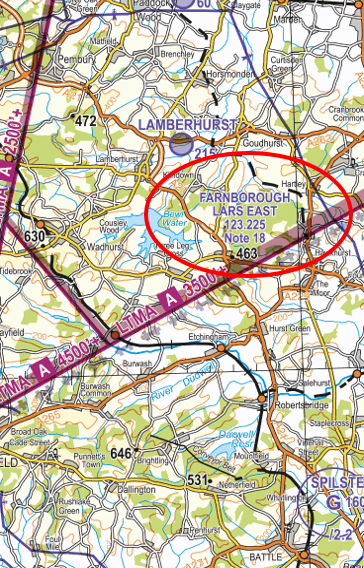

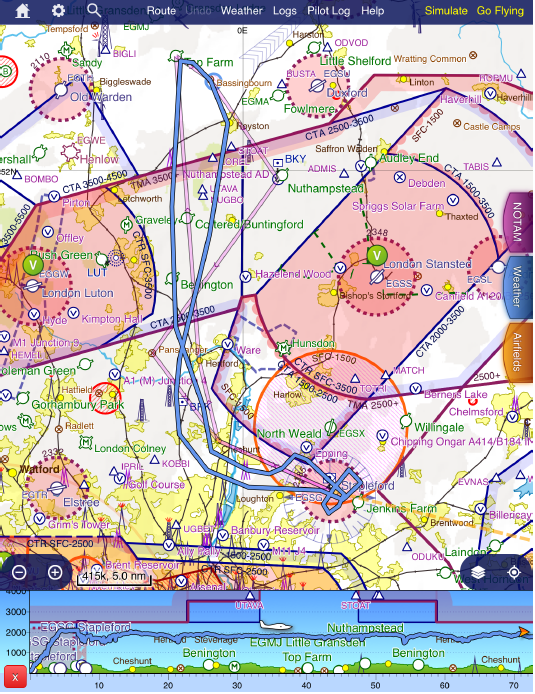

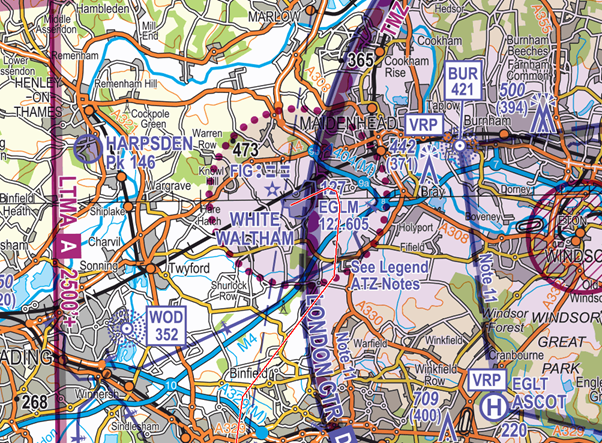

Figure 1: The aircraft entered the Class D CTA-1 indicating 2,100 feet where the base of controlled airspace is 2,000 feet AMSL.

Pilot

The pilot reported that they had planned to fly a route anticlockwise round the London CTR. The route had been planned on a VFR Moving Map as follows:

Bovingdon VOR/DME (BNN) – Woodley NDB (WOD) – Farnborough Airport (EGLF) Zone Transit – OCK

The pilot reported that a zone transit was sought through Farnborough’s CTR and granted not above 2,000 feet to the west of Bagshot mast. Once outside controlled airspace, approval was given to take up their own navigation direct OCK under a Basic Service. During this phase the pilot was advised they had climbed into controlled airspace, at which time they apologised and immediately descended. The pilot reports that from their VFR Moving Map log, it would suggest they had entered controlled airspace for approximately 2 minutes. The pilot stated that they encountered significant thermal activity when proceeding direct OCK necessitating power changes and inputs to maintain a constant altitude from time to time during the flight.

In discussion with the pilot post event

The pilot explained that this cross-country flight was conducted to maintain their currency and prevent skill fade. The pilot further explained that flying this route, around controlled airspace, was intended to not only help to maintain their flying skills but also allowed them to check that the aircraft’s avionics worked as expected.

In the lead up to the infringement, the pilot stated they were tracking direct OCK. It was at this time they experienced significant tail-lift pushing them up to 2,100 feet and thus infringing the Farnborough CTA-1. The pilot confirmed they were not using the aircraft’s autopilot. They further explained that it was whilst transiting initially beneath the CTA-1, they were tuning in to the Ockham VOR/DME.

The pilot expressed they wanted to remain as high as possible at all times whilst operating outside of controlled airspace in order to provide time to troubleshoot and perform a forced landing if necessary. Their rationale was based on having previously experienced 3 partial power losses. As a result, they had become normalised to fly at a higher altitude wherever possible. The pilot explained that they found cockpit workload inevitably increased when flying around the London CTR due to the extent of controlled airspace and ‘choke points’ around the area.

Findings/Causal Factors

The infringement occurred due to an inadvertent climb into the CTA when planning to fly 100 feet below the vase of controlled airspace due to thermic activity and possibly compounded by distraction when setting their VOR equipment. Whilst the pilot reacted quickly to the climb, the response was insufficient to prevent the aircraft entering controlled airspace as the aircraft was operated just below the base. However, a number of valuable lessons emerged from this occurrence which may be relevant to us all as pilots.

It was established that the event was underpinned by lapses in pre-flight planning, Threat and Error Management (TEM) and management of the flight.

The pilot is to be commended for their openness and post-occurrence actions. The pilot carried out post-flight analysis and commented on causal factors. As is the case in most occurrences there was not a single cause, several contributory factors led to how the infringement developed.

Pre-Flight Planning

Route planning

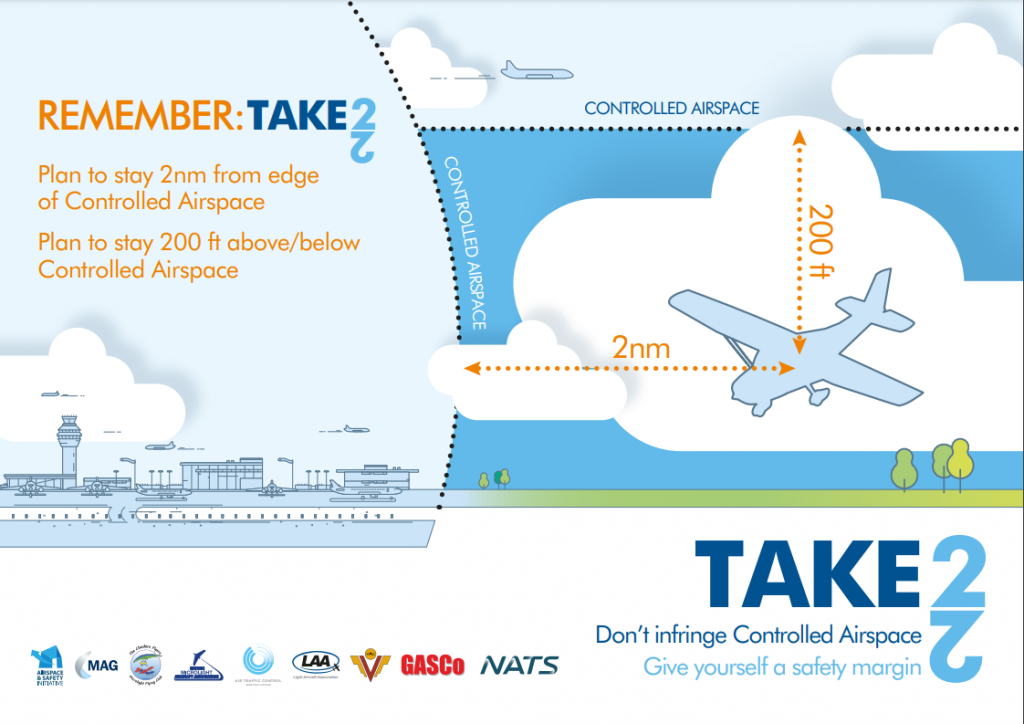

The pilot elected to fly 100 feet below the base of controlled airspace in thermic/turbulent conditions. Pilots are advised to maintain adequate separation from notified airspace through the application of the ‘Take 2’ guidance (where able, plan to remain at least 2NM from the edge or 200 feet below the base of the subject airspace) to avoid airspace infringements. The ‘Take 2’ initiative is neither a buffer based on State policy, nor is its application mandatory; it is merely guidance based on the principle of good airmanship, introduced by pilots to help their fellow pilots and other airspace users. If following this guidance places the pilot in an uncomfortable position, this is a threat, and should be addressed during the pre-flight planning stage, with potentially a less restrictive route decided upon.

Meteorology Planning

The pilot reported they encountered significant thermal activity when proceeding direct OCK necessitating power changes and inputs to maintain a constant altitude from time to time during the flight.

A thorough weather brief using regulated information from the Met Office Aviation Briefing Service website, for example Met Forms F214 and F215, should be completed prior to every flight and associated risks incorporated into the planned route. Local conditions can vary from what is forecast, reinforcing the advice to maintain adequate separation from notified airspace through the application of the ‘Take 2’ guidance. The recommended 200 feet distance may need to be increased during flights where turbulence or thermic conditions are encountered to prevent inadvertent climbs into controlled airspace.

Threat and Error Management (TEM)

Distraction

The pilot explained that whilst transiting beneath CTA-1, they were tuning in to the Ockham VOR/DME. Although it cannot be ascertained to what extent tuning into the VOR contributed to the infringement, operating proximate to controlled airspace and having just completed a zone transit and now prompted to reset the squawk, the pilot could have become task saturated. By not following the ‘Take 2’ guidance would further have reduced the pilot’s ability to remain below controlled airspace. In this instance, applying the ‘Aviate, Navigate, Communicate’ principle would have allowed the pilot to maintain their altitude relative to the base of controlled airspace. Thorough pre-flight planning would enable this threat to be identified, and the pilot could have planned to tune into the Ockham VOR/DME at a time where cockpit workload was low (prior to the Farnborough CTR transit).

VFR Moving Map

The pilot was using a VFR Moving Map application; however, it could not be ascertained what alerts were present, if any, and the response to them. When configured correctly VFR Moving Maps can not only enhance a pilot’s situational awareness in flight, but they can help to reduce confirmation bias and can also offer timely alerts to airspace and aviation hazards. Operating around controlled airspace will alert the pilot to controlled airspace proximate to their position (if configured correctly); however, there is a human factors element present whereby the pilot intuitively accepts/cancels the alert without having fully assimilated the information given. This can be especially true in cases where pilots are familiar with the airspace or are subjected to constant multiple alerts leading to ‘alert fatigue’. Every flight, even along routes previously flown, should be thoroughly planned, addressing the potential threats and errors for each phase of flight.

The CAA actively encourages pilots to use VFR Moving Maps in conjunction with the CAA/NATS Chart. However, VFR Moving Maps are not regulated by the CAA, and it is important to understand their limitations including differing depictions and altitude inaccuracies. They should not be used as your sole means of planning and navigation and a backup should be carried to prevent a loss of situational awareness should your device malfunction.

Summary

In conclusion, Human factors play a major role in many airspace infringements and in this case, the desire to remain as high as possible when flying outside of controlled airspace and distraction, resulted in the pilot inadvertently climbing into controlled airspace after the significant thermic conditions encountered. The pilot carried out effective post flight analysis and was open and honest about the occurrence in line with Just Culture.

Focus on

- Threat & Error Management

- Pre-flight Planning and Preparation

- Distraction and Interruption (CAA Safety Sense)

- Meteorology Planning (UK Met Office)

- VFR Moving Maps (CAA Safety Sense)

- ‘Take 2’ Initiative

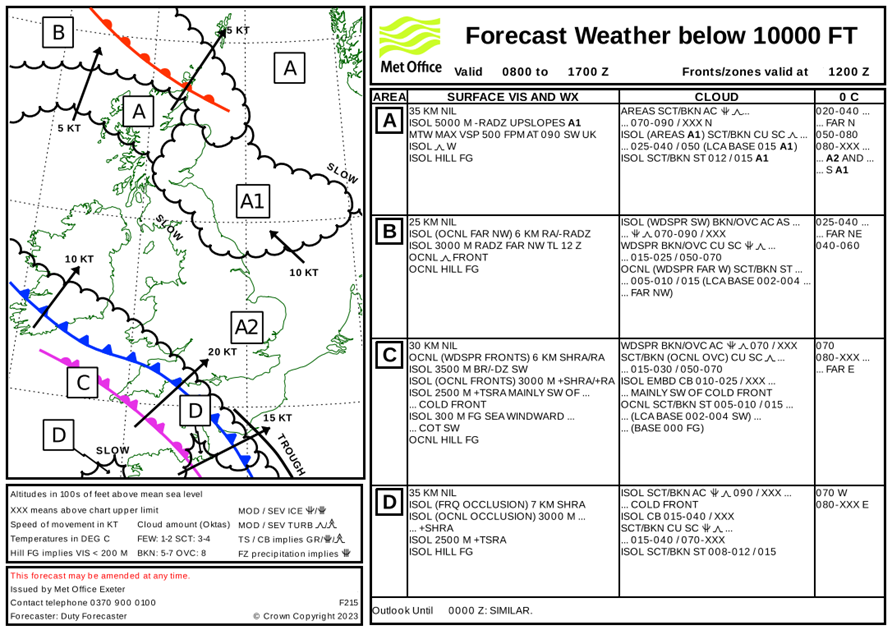

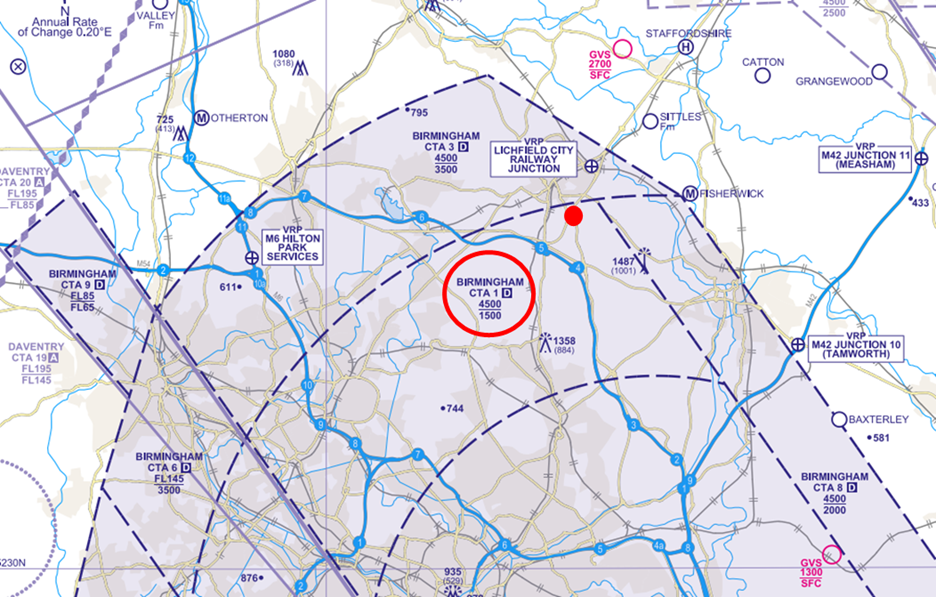

Infringement of Class D airspace – Birmingham Control Area 1

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing Aeroplane |

| Type of Flight | Recreational Flight |

| Airspace/Class | Birmingham CTA-1 / Class D |

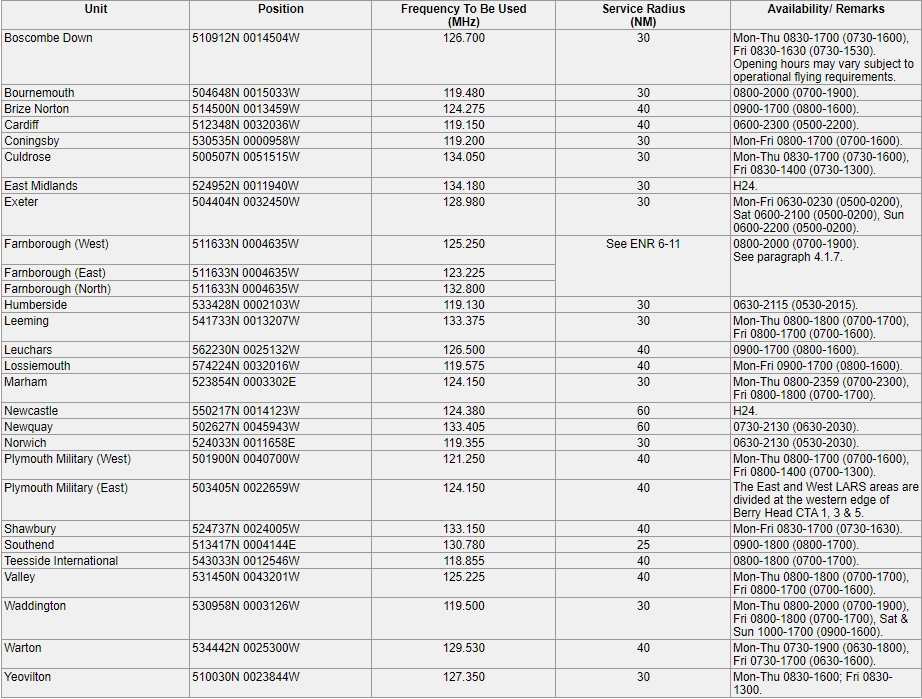

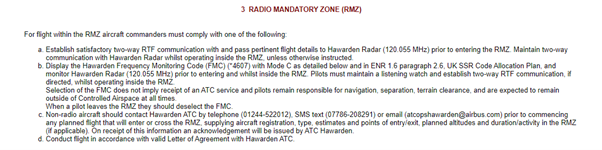

The Air Traffic Controller

The Air Traffic Controller reported that Runway 33 was in use at Birmingham with one aircraft shortly to depart. The controller was alerted to an unknown aircraft entering CTA-1 indicating 1,900 feet and squawking 0010 (the Birmingham Frequency Monitoring Code). Using MODE S derived information, the controller made a transmission to the pilot and asked them to descend immediately. The departing aircraft was instructed to depart straight ahead to maintain separation to the west of the infringing aircraft. The pilot stated they were mistakenly inside the CTA and descended; the aircraft was identified, issued with a discrete squawk and, once clear of the CTA, offered a Basic Service. Sometime later the aircraft climbed again into the CTA to 1,600 feet and, when informed of the climb, the pilot carried out an immediate descent.

The Pilot

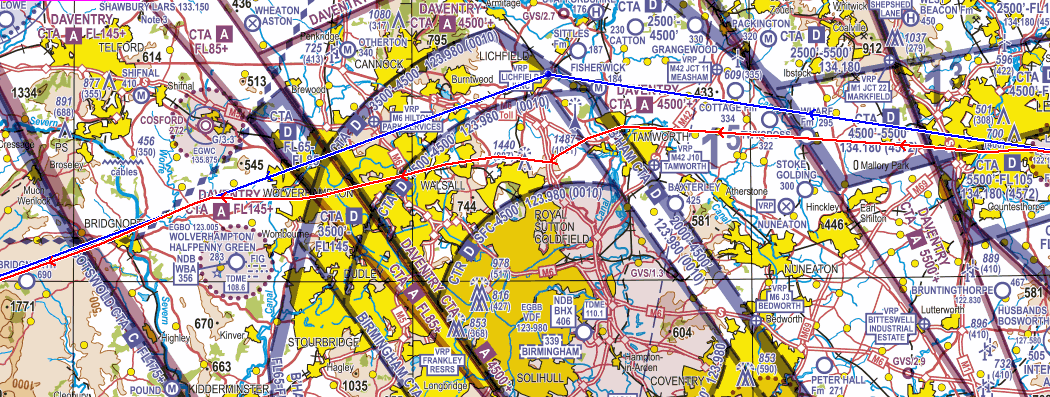

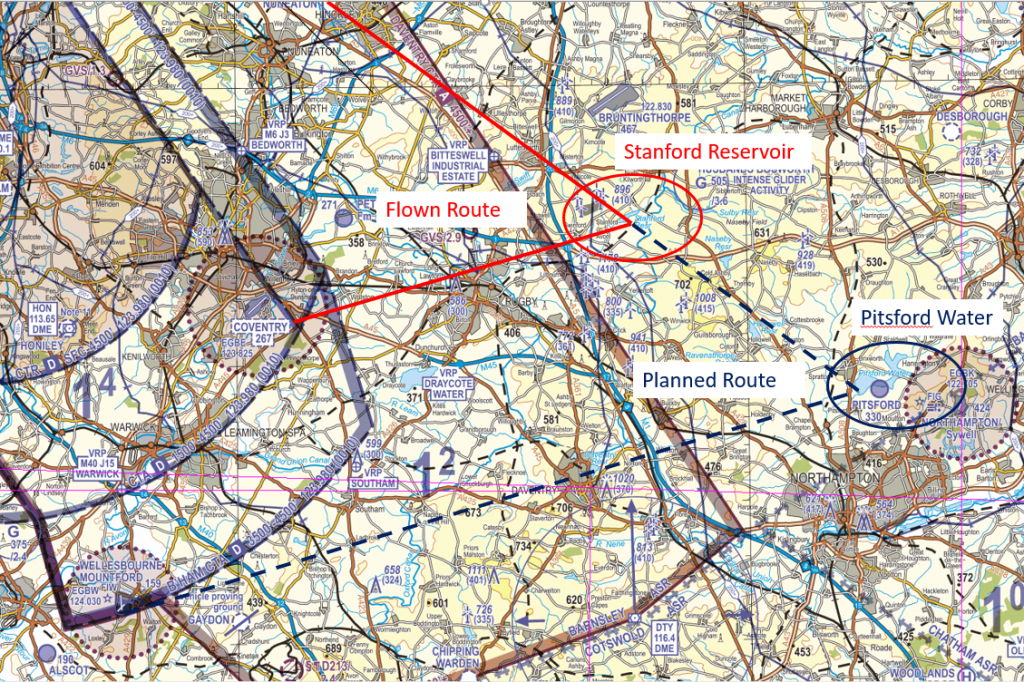

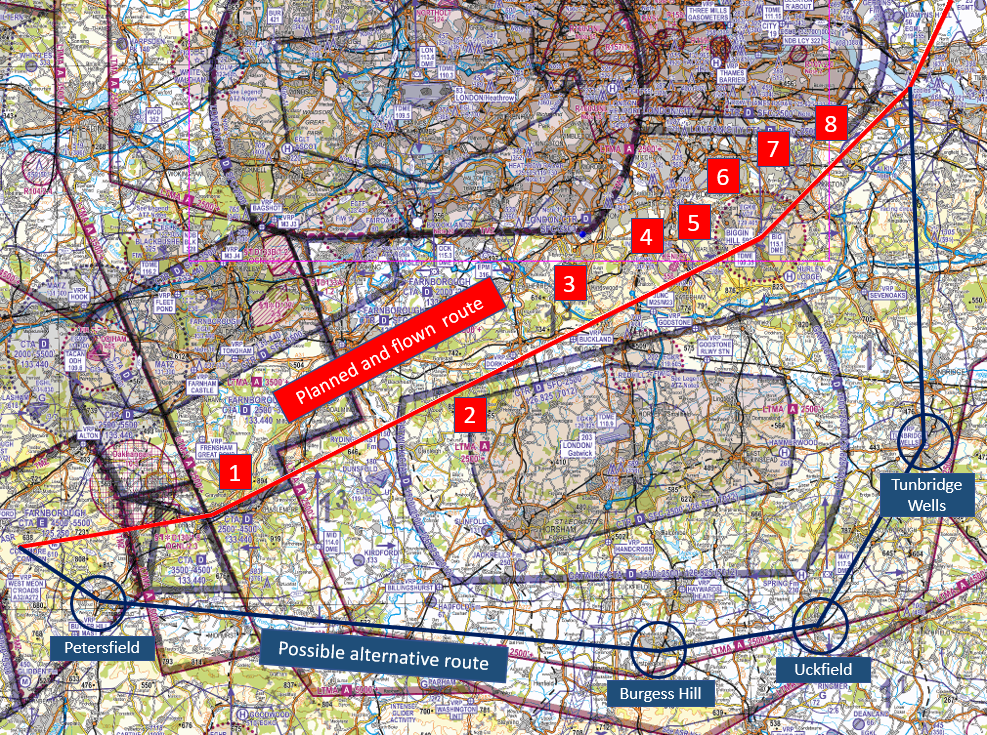

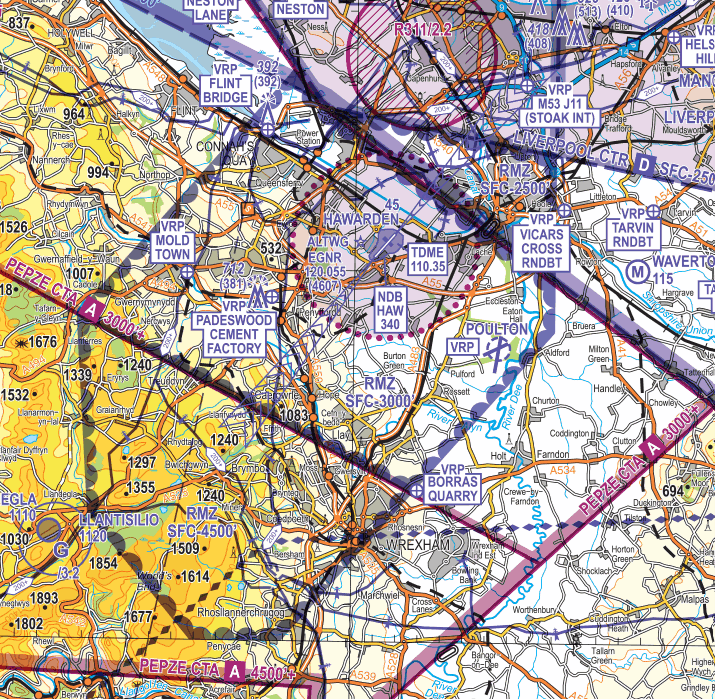

The pilot was prompt to submit a comprehensive report to the CAA. They reported that the aircraft had recently had a complete avionics refit with all original radios and navigation equipment replaced with fully integrated GPS/NAV/COM/MFD equipment, Electronic Flight Instruments and an autopilot. Initial flights post-installation were carried out for the pilot to become familiar with the basic instrumentation; the subject flight was planned for a longer distance to test the autopilot. The pilot openly admitted that the new avionics were not the reason for the infringement but “sloppy planning” carried out on the morning of the flight was a contributory factor. In that planning session, the pilot had ‘rubber banded’ the magenta line on the Moving Map. The red line in Figure 1 shows the route planned and that flown. Having taken the northern route around Birmingham many times, after departure the pilot usually routed at 1,900 feet to Lichfield Disused, then west between Cosford and Wolverhampton Aerodrome Traffic Zones taking them below the Birmingham CTA-3 with a base of 3,500 feet (blue line in Figure 1).

On the day of the infringement, the pilot followed their plan that took them west through, and not below, the similarly shaped but lower CTA-1 which has a base of 1,500 feet. On hearing their callsign broadcast by the Birmingham air traffic controller, the pilot’s first instinct was to disengage the autopilot and follow the requests of the controller. They then accepted a basic service and a discrete squawk. The second climb was thought to have occurred as the pilot wouldn’t normally fly as low as 1,500 feet over the built up areas to the west of Aldridge towards Walsall; they reported that they were most likely conscious of a lack of clearance with the terrain which, in that area, lies between 450 feet and 500 feet amsl. The rest of this flight, and the return flight home was uneventful.

The pilot added that on any other day they were sure they would have noticed the mistake of their plan in the air because the route was clearly wrong. However, distraction caused by focussing on the new avionics drawing more of their attention led them to miss the planning error.

After the occurrence, the pilot elected to take time with an instructor who was familiar with the new avionics to carry out some more familiarisation training and navigation practise.

Causal Factors/Findings

The pilot is to be commended by their openness and post-occurrence actions. This occurrence demonstrated the benefit of using a Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC); the pilot reported that they use them whenever they are available in the areas in which they are flying. This positive approach to, and correct use of, the FMC allowed the initial infringement to be resolved promptly by the controller and pilot. In addition, the pilot correctly operated their transponder with MODE C (ALT) alerting the controller to the infringement; had MODE C not been operated, the controller would have been correct to have ‘deemed’ the aircraft to be below the CTA. Had that been the case, the risk of a mid-air collision or the infringing aircraft being affected by wake turbulence would have been heightened.

Poor planning and a failure to double check the route and associate altitudes of the airspace resulted in confirmation bias that they were able to fly at 1,900 feet. In the planning phase, by creating a back-up on a paper chart, you are often notice additional information/details that you don’t always notice on your Moving Map display.

Even though the pilot was flying with a Moving Map, it is not known why there was no response to the alert. It is possible that the confirmation bias led the pilot to dismiss the alert without noting its subject. When properly configured and used, an airspace warning would have been given the pilot a timely alert of their proximity to controlled airspace.

In summary, the pilot did not carry out sufficiently detailed pre-flight planning which, combined with confirmation bias and distraction from overly focussing on new avionics, resulted in their flying into Class D controlled airspace without an air traffic control clearance. However, textbook use of an FMC allowed the infringement to be resolved in a prompt manner.

Despite some errors associated with Human Factors, the pilot has embraced a Just Culture and identified the benefits associated with completing the appropriate refresher training which was carried out with a Flight Instructor.

Focus on

- Pre-flight planning and preparation

- Human Factors and confirmation bias

- Use of Moving Maps

- Threat & Error Management

- Provision of an Air Traffic Service: Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS)

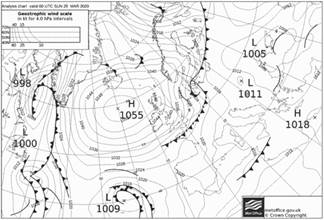

Infringement of Class D airspace – Stansted Control Area 4 and Luton Control Area 1

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing Aeroplane |

| Type of Flight | Recreational Flight |

| Airspace/Class | Stansted & Luton CTA / Class D |

The Air Traffic Controller

The Air Traffic Controller reported that they had traffic on a right-base for Runway 25 at London Luton Airport descending to 3,000 feet. A radar contact was seen to climb into controlled airspace south of Royston passing 2,600 feet before stopping the climb at 3,000 feet on an approximate track of 250o. Traffic information was passed to the Luton arrival aircraft and it was turned onto a shorter final to avoid the infringing aircraft. At this point the unknown aircraft selected 0013 squawk and the controller was able to ascertain their callsign and get 2-way communication with him. The pilot informed the controller they were leaving controlled airspace to the north which they subsequently did. The aircraft was then identified and given a service as per the pilot’s request. The Luton arrival was then re-vectored and completed a safe approach to land.

The Pilot

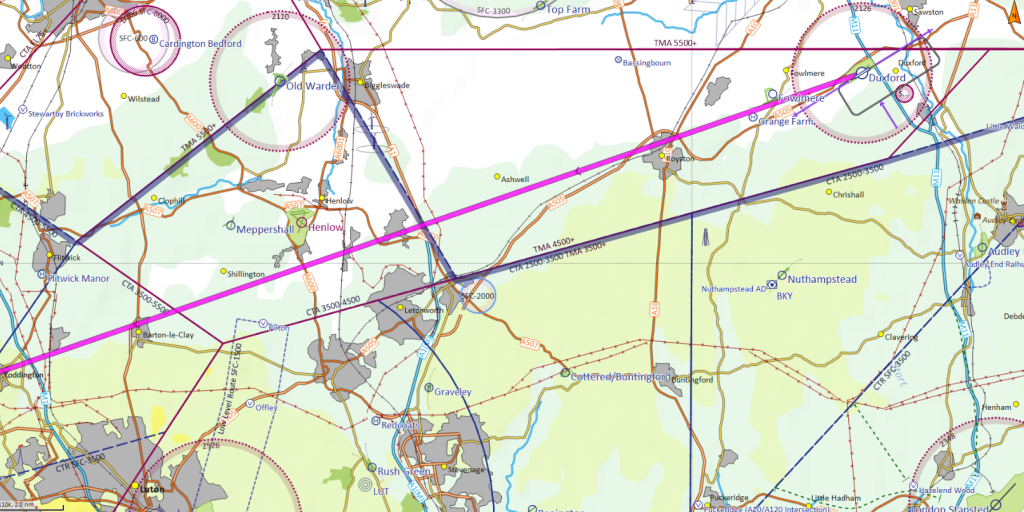

The pilot reported carrying out a recreational flight from Duxford to Cornwall via Wing (west southwest of Leighton Buzzard) to route to the north of the Luton Control Zone. The route was planned to be flown at 3,000 feet to remain below the CTAs with a lowest base of 3,500 feet. The plan was to climb straight ahead to 3,000 feet on a heading of 251o after departure from Runway 24 (Figure 1).

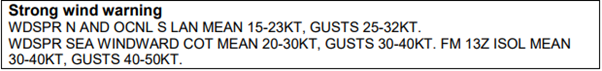

On the morning of the flight there was a strong northerly wind flow down the east side of the UK. The associated TAF were as follows:

- Stansted: 300/14, PROB 40 TEMPO 2606/2609 32018G28

- Luton: 300/14, TEMPO 2606/2706 33018G28.

- The forecast 2,000 feet wind at 5230N 00E was 340/35 (35 knots at 90o to the planned track)

Just before departure an aircraft called Duxford Information to state they would be conducting visual circuits at Fowlmere (2.5NM west southwest of Duxford). On lining up for departure the pilot was informed of the traffic at Fowlmere and the surface wind “being something like 310/16”.

On climb out the pilot encountered the most vigorous turbulence that they could recall flying in for many years. They elected to hold runway heading as best they could to climb straight ahead out of the ATZ without turning right to the track of 251o degrees to enable them to remain clear of Fowlmere (blue line in Figure 2); the passenger was asked to look out for the Fowlmere circuit traffic. Given the turbulence, the pilot elected to climb at best rate of climb speed, which was approximately 80 knots, with the aim of getting into smoother air as soon as possible.

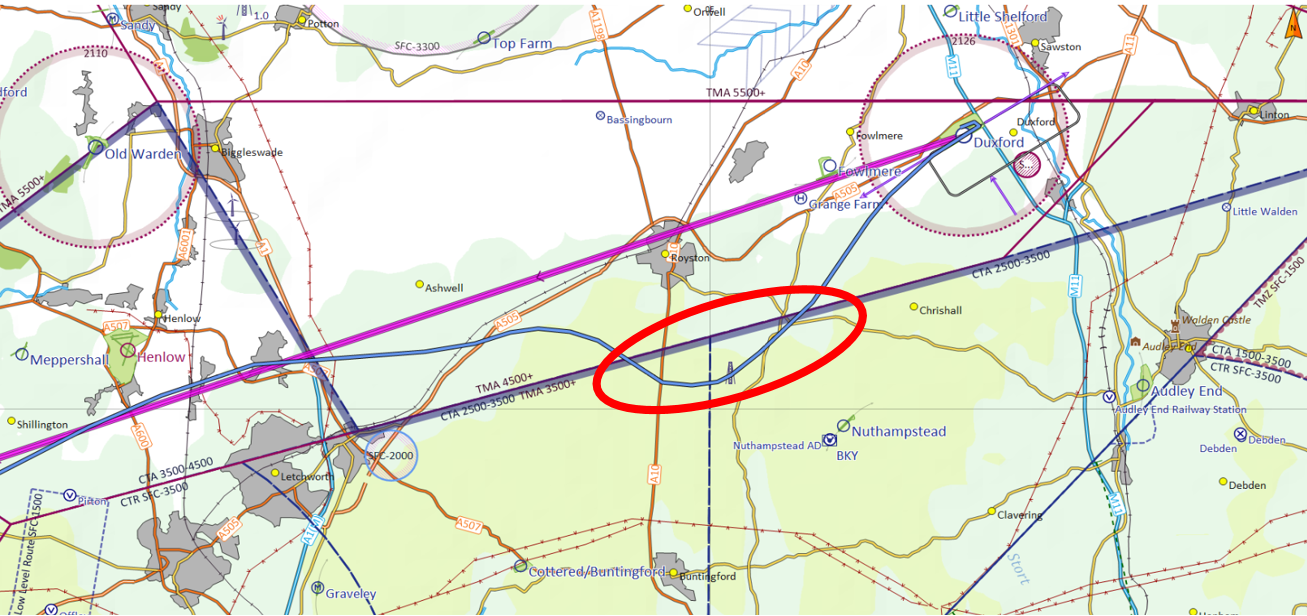

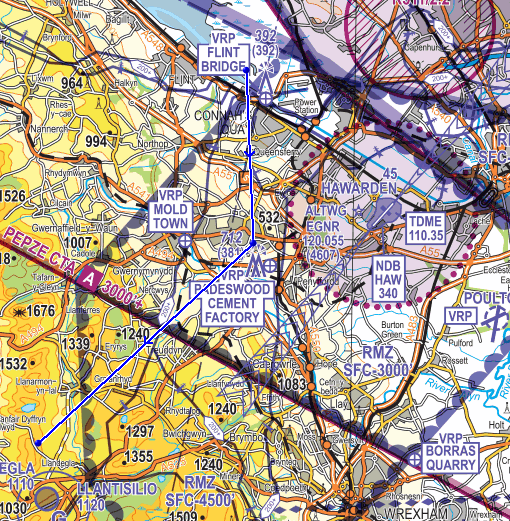

Once clear of Fowlmere, the pilot called Duxford to leave their frequency, changed to Luton Radar on 129.550 MHz and then selected the Luton Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) of 0013. With the long nose of the aircraft, forward visibility is limited when climbing steeply; unfortunately, that meant fewer visual cues as to actual track were available to the pilot. As the aircraft approached 3,000 feet the pilot asked the passenger to pass them their Moving Map tablet that had been running since departure. The pilot was just noting they had had flown to the left of the airspace line (magenta line in Figure 2) when Luton Radar called to advise that they were indicating at 2,800 feet and was advised immediate descent to below 2,500 feet. Realising their error, the pilot responded that they were descending and turning north to head out of the Stansted CTA as quickly as possible.

ATC aspect

The airspace and track where the aircraft infringed is routinely used by Luton and Stansted traffic. This incident took place when the traffic was light and therefore the consequences of the infringement was minimal. Following agreement with the pilot of the arriving aircraft the controller re-positioned the aircraft and ensured minimum separation was achieved between the two aircraft However, in normal traffic levels with a continuous stream of arrivals the ability to reposition the aircraft without any impact on subsequent arrivals is unlikely. The workload increase for pilot and controller is significant under these circumstances with safety remaining paramount. One infringement of only a few minutes can result in many minutes of delay to operators, with additional fuel burn and emission also a consideration.

Causal Factors/Findings

The pilot carried out detailed and effective planning in route selection to remain outside controlled airspace and included the use of FMC along the route. In addition, they were equipped with a Moving Map which was intended to be used actively en-route. They also recognised the Threat associated with dual operations at Duxford/Fowlmere.

However, a minor change to the plan moments prior to departure allowed the introduction of lapses in wider Threat and Error Management. The decision to fly further south in strong cross winds and to climb at a higher rate resulted in the aircraft’s track being affected greater over a shorter distance the aircraft drifting further south of track than had been anticipated. The pilot, unaware of their ground track due to reduced forward visibility associated with the aircraft’s attitude then lost situational awareness and extended beyond that required to avoid the traffic flying circuits to the north of Fowlmere. By the time the aircraft was south abeam the Runway 25 threshold at Fowlmere, it was 1.2NM south and passing 1,500 feet. In addition, had the pilot identified that routing to the south of Fowlmere would take them closer to the Class D CTAs they may have identified the increased value to using the Moving Map. This would have enabled them to regain situational awareness lost through the aircraft’s attitude. The pilot could have either turned right back onto track or stop their climb below 2,500 feet to remain below the CTA. However, the pilot was faced with several distracting factors from their original plan and their capacity was rapidly being used in handling the aircraft in extremely turbulent conditions whilst considering the traffic at Fowlmere and the wellbeing of their passenger.

In their wider plan, the pilot had considered the Take 2 aspect to remain clear of controlled airspace but that was not revised following the amended plan to deviate to the south of Fowlmere and thereby fly close to the CTA. Had the pilot only climbed to, for example 2,300 feet, until closer to Royston, the infringement could also have been avoided. This probably did not enter the pilots thought process as the focus was on climbing out of the turbulence, avoiding the Fowlmere visual circuit, and selecting the next radio frequency and FMC.

Notwithstanding the lapses in Threat and Error Management, the pilot’s initial plan was good and incorporated several key measures to prevent airspace Infringements:

- Comprehensive planning including airspace avoidance and meteorology;

- Use of a Moving Map; and

- Use of an FMC.

That decision to use an FMC enabled early intervention by air traffic control to assist the pilot and resolve the situation promptly. In addition, detailed post-occurrence analysis and open and detailed reporting by the pilot enabled lessons to be identified to avoid a recurrence.

Focus on

- Pre-flight planning and preparation

- Human Factors

- Use of Moving Maps

- Threat & Error Management

- Frequency Monitoring Codes (Listening Squawks)

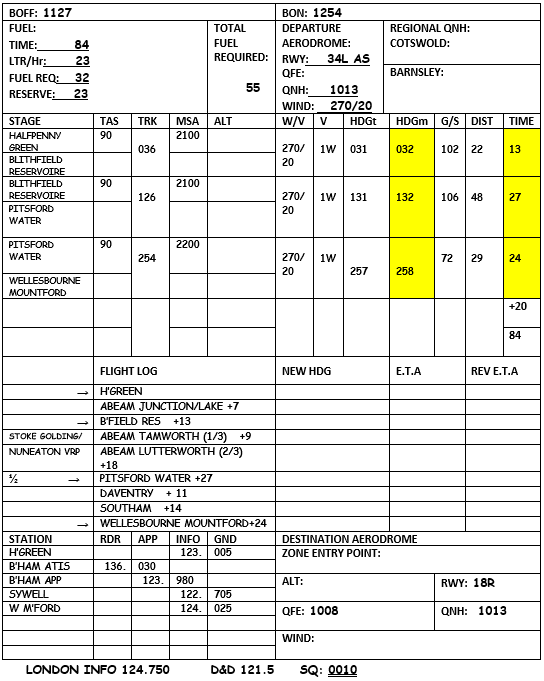

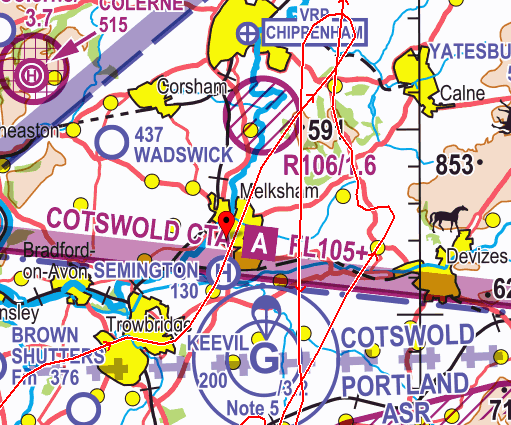

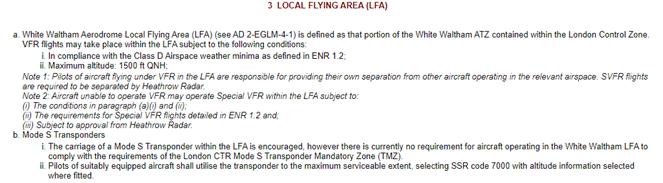

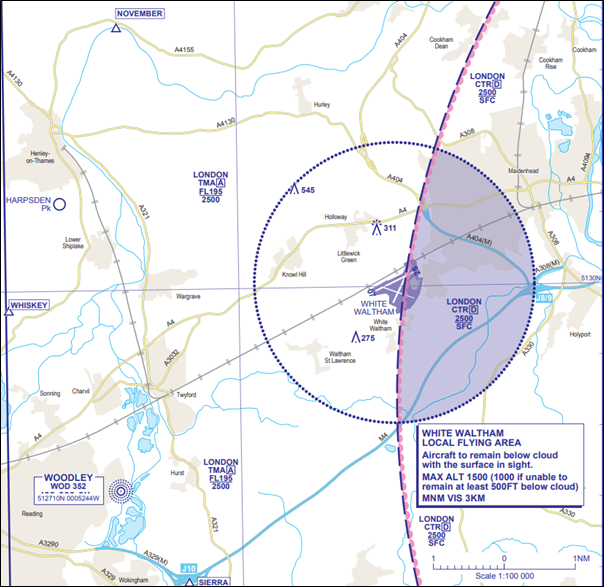

Infringement of Class A airspace – Cotswold Control Area

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing Microlight |

| Type of Flight | Instructional Flight |

| Airspace/Class | Cotswold CTA / Class A |

Met information

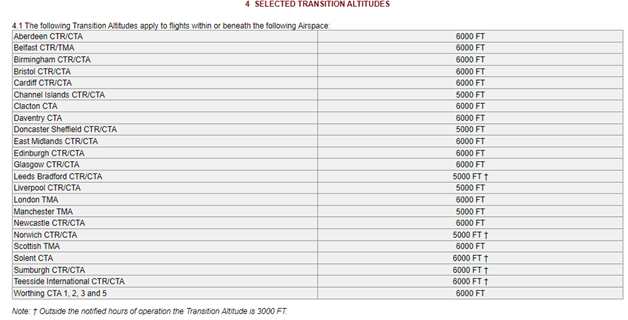

At the time of the infringement the local QNH both at Brize Norton and Fairford was 1003 hPa. The cloud was BKN (5-7 oktas) at 4,800 feet and the forecast 5,000 feet wind on the UK Low-level Spot Wind Chart (Form 214) was 190/30.

The Air Traffic Controller

The Air Traffic Controller reported observing an unknown aircraft squawking 7000 indicating FL071 (7,100 feet based on 1013 hPa) enter the lateral confines of L9 in the vicinity of the IFR reporting point GAVGO, which is near Swindon. The aircraft remained in L9 for a period of 9 minutes 32 seconds. The aircraft was later observed to change to a Brize Norton conspicuity squawk (3737) but the Brize Norton Air Traffic Service Unit was unable to establish contact with the pilot.

The Pilot

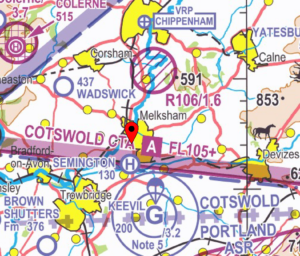

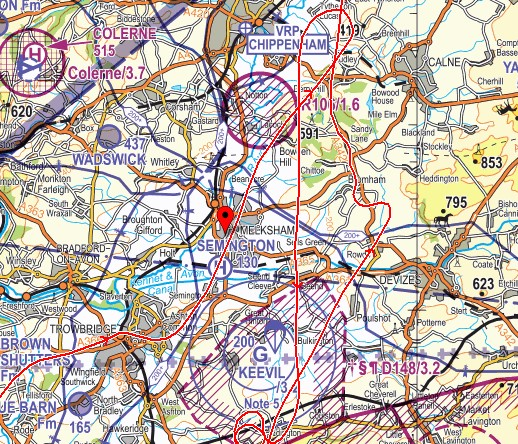

The pilot reported that the training flight was being conducted in very local and familiar airspace. Navigation was being carried out using a 1:250K VFR chart with no GPS/Moving Map. The initial part of the flight was conducted under a layer of cloud (reported to be at 4000-5000 feet) but training was made difficult due to turbulence. The aircraft was turned south to remain clear of the Cotswold CTA with a base of FL065 and climbed above the cloud. Due to strong winds aloft, the aircraft was not positioned as far south an anticipated and with repeated turns the aircraft was ‘blown back’ into L9. The pilot found it difficult to determining their position due to only intermittent sight of the surface as a result of operating above cloud; they felt that the infringement was increased due to the low QNH.

Causal Factors/Findings

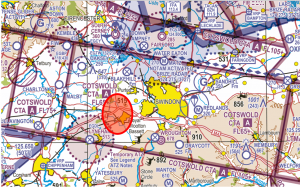

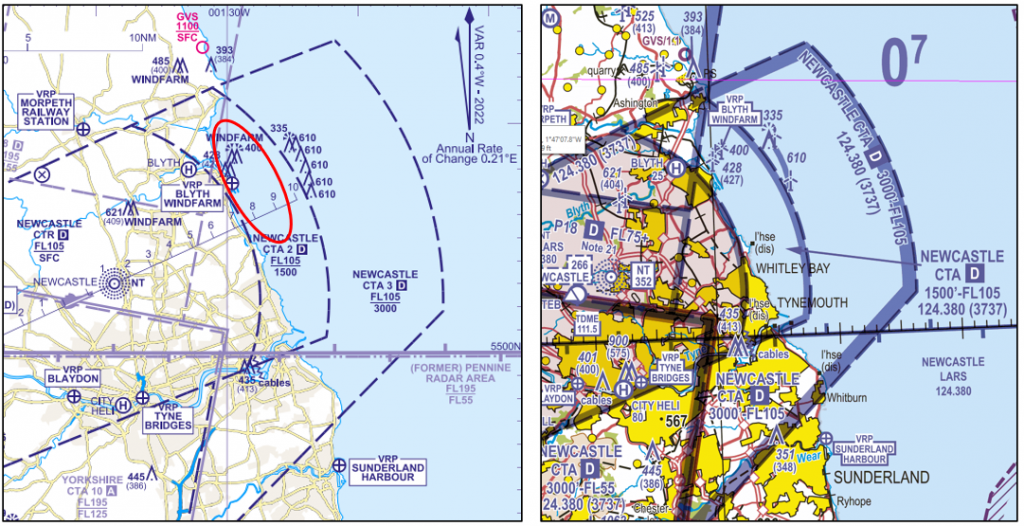

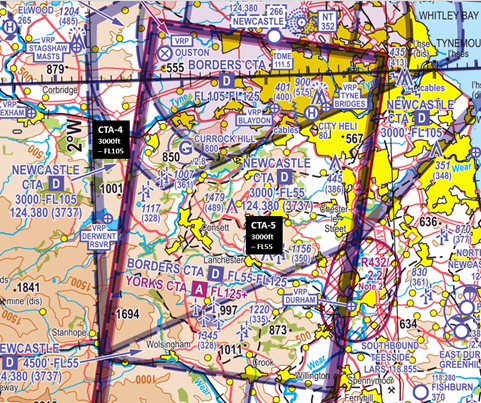

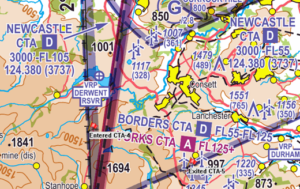

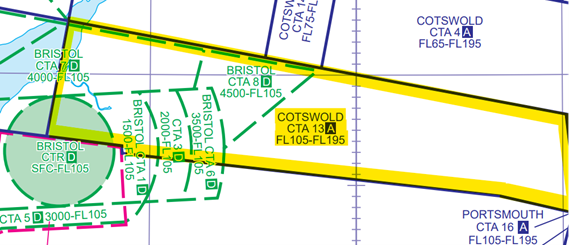

1:250,000 VFR charts have a vertical limit of airspace of 5000 feet ALT. The decision to climb to an altitude where no airspace information was available in the cockpit was the result of the instructor being inadequately prepared for this flight. Figure 1 compares the information available on the 1,250,000 with the 1:500,000 chart. Figure 2 shows the warning annotated on all 1:250, 000 charts to remind users of the vertical limits.

The infringement lasted 9 minutes 32 seconds. Figure 3A shows the area on a 1:500,000 chart. Figure 3B shows the same area on the chart available to the instructor in the cockpit.

When it became clear that prevailing weather conditions required a change to the plan after departure the instructor should have either abandoned the flight or revised their plan. To mitigate against risks associated with over confidence/complacency their revised plan needed decisions based on aeronautical information available in flight, rather than perceived knowledge.

The instructor chose to operate without a Moving Map. The CAA and safety partners actively encourage all pilots to incorporate the use of Moving Maps in both pre-flight planning and in-flight. When properly configured and used effectively, a visual and aural airspace warning would have been given alerting the pilot of their proximity to controlled airspace.

The instructor failed to recognise the Threats associated with cloud base and strong winds aloft. This resulted in the pilot losing situational awareness of the aircraft’s position. Once above cloud and unable to maintain positional awareness, the pilot made an Error in not requesting an air traffic service (ATS) from the local Lower Airspace Radar Service unit; Brize Norton is just 12NM from the location of the infringement.

At 1003 hPa, the QNH was not uncharacteristically low but it meant that the aircraft was some 300 feet higher on the local QNH when adjusted for the Standard Altimeter Setting (the correct pressure datum of the Cotswold CTA). However, the aircraft was still flown some 600 feet higher than the base of controlled airspace. Had the Instructor had the correct chart available and having stated they were aware of the Class A airspace with a base of FL065, they should have incorporated a maximum altitude of 6,000 feet on the QNH of 1003 hPa into their plan to remain below controlled airspace. This, in line with Take 2 guidance, would have ensured they were operating below the CTA and have a buffer of 200 feet to allow the management of the Threats associated with turbulence or student handling error.

When the pilot eventually displayed a Brize Norton SSR code the unit was unable to establish 2-way communications. In the first instance a pilot should only select the conspicuity code (3737) when instructed to do so or in accordance with local procedures. Had the pilot intended to display the Frequency Monitoring Code (Listening squawk) the code selected should have been 3727 with the relevant frequency selected (124.275 MHz).

Instructors often lower the volume of the comms panel/radio during instructional flights as constant R/T can distract the student and impede in-cockpit talk between instructor and student. It is not uncommon in occurrence involving instructional flights for ATC not to be able to establish communication with the pilot for this reason.

Focus on

- Pre-flight planning and preparation

- Use of Moving Maps

- Threat & Error Management

- Altimetry – Key tips

- Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS)

- Frequency Monitoring Codes (Listening Squawks)

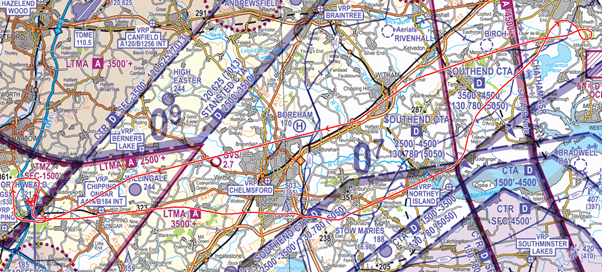

Infringement of Class D and Class A airspace – Gatwick Control Area and London Terminal Control Area

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing Microlight |

| Type of Flight | Recreational Flight |

| Airspace/Class | Gatwick CTA / Class D and London Terminal Control Area (LTMA) / Class A |

The Air Traffic Controller

The Air Traffic Controller reported receiving a Controlled Airspace Infringement Tool (CAIT) alert of an aircraft squawking 7000 indicating 1,800 feet briefly enter the Gatwick Control Area (CTA). Some 13 minutes later, the aircraft was seen to enter the LTMA in the vicinity of the Mayfield VOR/DME (MAY) at 2,900 feet. Whilst the controller was planning what action was required to ensure separation was maintained with an aircraft inbound to Gatwick Airport, the unknown aircraft descended below controlled airspace.

These infringements did not result in a Loss of Separation due to the significant reduction of commercial traffic at Gatwick associated with COVID-19. But under normal traffic conditions, due to the location of the infringements, this event may have caused a safety event and considerable workload for commercial pilots and controllers.

The Pilot

The pilot reported that the flight was planned to fly from Headcorn to Deanland and return to Headcorn later. The cloud base at the time was approximately 1,600 feet and the visibility was good. Despite the good visibility, the lower than expected cloud base did cause some distraction.

The aircraft was equipped with, and the pilot was operating, a MODE S transponder and squawking 7000 with MODE C. Whilst aware of the benefits of moving map technology, the pilot had chosen not to use one as they did not want to become over reliant on it to avoid degradation of conventional navigation skills.

The pilot had planned the flight, and was using a 1:250, 000 VFR chart, although no route line was drawn on the chart. Flying a heading of 240 degrees the pilot misidentified Bewl Water as Darwell Reservoir resulting in them being north of their intended track. This led to being too far to the west when trying to visually locate Deanland, the destination aerodrome. Having failed to locate Deanland, the pilot decided to return to Headcorn and turned left onto a reciprocal track when approximately 3NM southeast of Haywards Heath. When the cloud base improved, a climb was initiated but as they were further west than they thought, the pilot infringed the LTMA as they were still under the area where the base is 2,500 feet.

Meteorology

The TAF at the time of the Infringement forecast an improving cloud base after 0700 hours UTC:

EGKK 060458Z 0606/0712 20007KT 9999 BKN010

TEMPO 0606/0607 BKN007

PROB30 TEMPO 0606/0607 6000 -RADZ BKN004

BECMG 0607/0610 SCT030

PROB30 0702/0707 8000=

The METARS as issued:

0750 EGKK 060750Z 19007KT 160V230 9999 BKN013 20/17 Q1007=

0820 EGKK 060820Z 21006KT 160V240 9999 BKN012 20/17 Q1018=

0850 EGKK 060850Z 22007KT 190V250 9999 BKN015 21/17 Q1018=

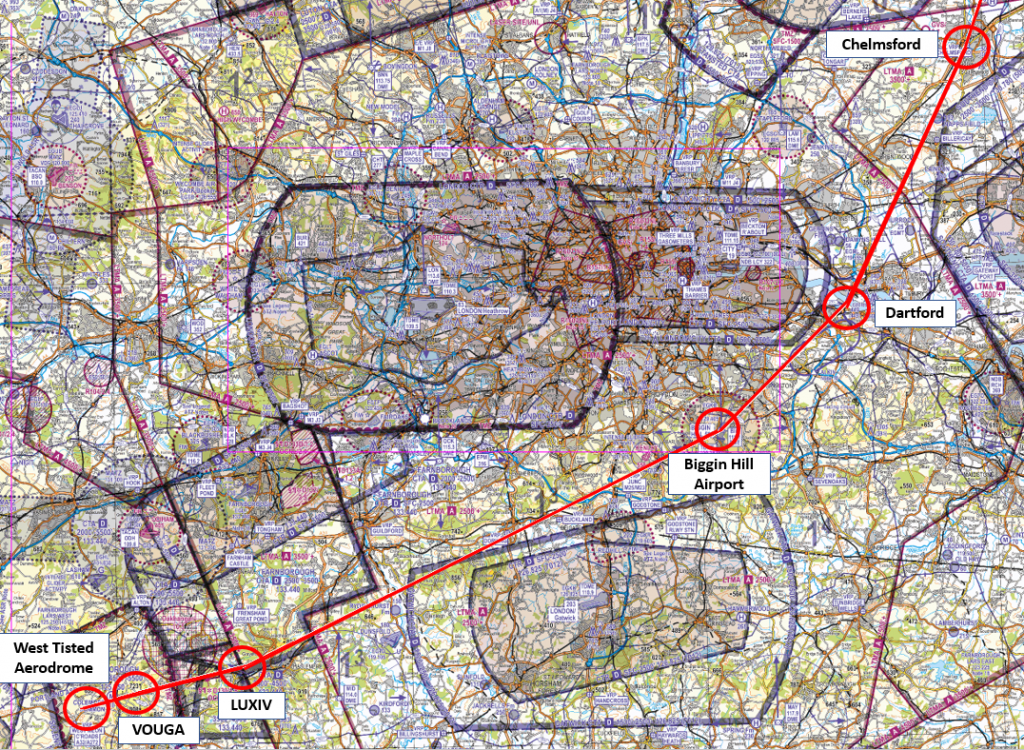

Causal Factors

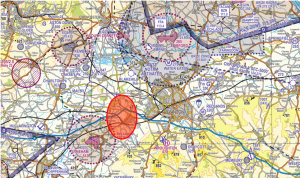

The pilot had planned to carry out a direct flight to Deanland. Based on the aircraft’s speed and the relatively short distance of the flight the decision to fly using 1:250,000 chart was sound and greater definition of route features were available. However, in selecting an initial incorrect heading, the outbound track was offset to the north of the water feature of Bewl Water (A in Figure 1). The pilot knew that they wanted to be north of Darwell Reservoir (B in Figure 1) and once airborne from Headcorn and visual with a large water feature, the pilot became subject to confirmation bias.

In the pilots mind they expected to see a water feature to the south. Because the pilot was familiar with the area and had flown the route many times, they knew that they needed to be just to the north of Darwell Reservoir. The sight of a body of water to the left of the route meant that the pilot’s expectations were confirmed, and the sensitivity of the error detection mechanism was reduced at a time when mental capacity was also taken up with the distraction of lower-than-expected cloud. By keeping Bewl Water to their left the pilot was destined to infringe the Gatwick CTA.

The pilot’s planning was complacent due to the number of times the route had been flown and their knowledge of the area:

- No attempt was made to obtain the upper winds by using the MetForm 214 or other APPS.

- A line was not drawn on a chart between Headcorn and Deanland.

- A Navigational Plan/ Log (PLOG) was not constructed for the flight.

As a result of the 2,000 feet wind on the day (approximately 180 degrees /10 knots), the heading flown gave a ground track (red line in figure 2) of approximately 250 degrees. The heading required to fly a direct track from Lashenden to Deanland was approximately 224 degrees (purple line in figure 2). With a lowering cloud base en route, the pilot became distracted from the navigation task and the effects of the initial heading error were not challenged.

The pilot’s normal method of navigation was to use dead reckoning techniques. Had the pilot used a moving map, even just as a back-up, they would have quickly identified that the aircraft was significantly off track and that Bewl Water was not Darwell Reservoir. In addition, as the pilot approached the Gatwick CTA, with correct configuration, a visual and aural warning could have been provided. These warnings are triggered when the horizontal and vertical trajectory would take an aircraft into a volume of controlled airspace. An onscreen warning is often accompanied by an audible alert, the form of which depends on the type of airspace, and a thick border may be drawn on the map accompanied by large coloured arrows to highlight which piece of airspace is associated with the warning. The CAA and safety partners actively encourage all pilots to incorporate the use of moving maps in both pre-flight planning and during flight.

At no time did the pilot believe they were lost. They became uncertain of their location when they were unable to locate Deanland which the pilot commented is not an easy aerodrome to locate due to the surrounding landscape. However, being unable to locate the aerodrome should have been a trigger to seek assistance from an Air Traffic Service Unit. A number of options were available including calling D&D on 121.500MHz for either a position fix or a steer to Deanland; calling Gatwick on 126.825MHz or Farnborough LARS (East) on 123.225MHz.

A chart showing areas of responsibility for the UK LARS units can be found in the UK AIP at ENR6.11. In the case of Farnborough LARS, there are annotations on the VFR Charts (see figure 3). A last barrier could have been the use of the Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) for Gatwick. Although the intended track of the flight would have been 2NM to the south of the published area for the Gatwick FMC (7012 and 126.825MHz), the first, brief, infringement, would have been acted upon by the Gatwick Director which may have acted as a trigger to the pilot that they were some 8.5NM north of track.

Focus on

- Use of Moving Maps

- Frequency Monitoring Codes (Listening Squawks)

- Threat & Error Management

- Confirmation Bias

- Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS)

Other narratives in this series can be found on the Infringement occurrences page

Infringement of Class D – Manchester Control Area

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing Microlight |

| Type of Flight | Recreational Flight |

| Airspace / Class | Manchester CTA / Class D |

Air traffic control

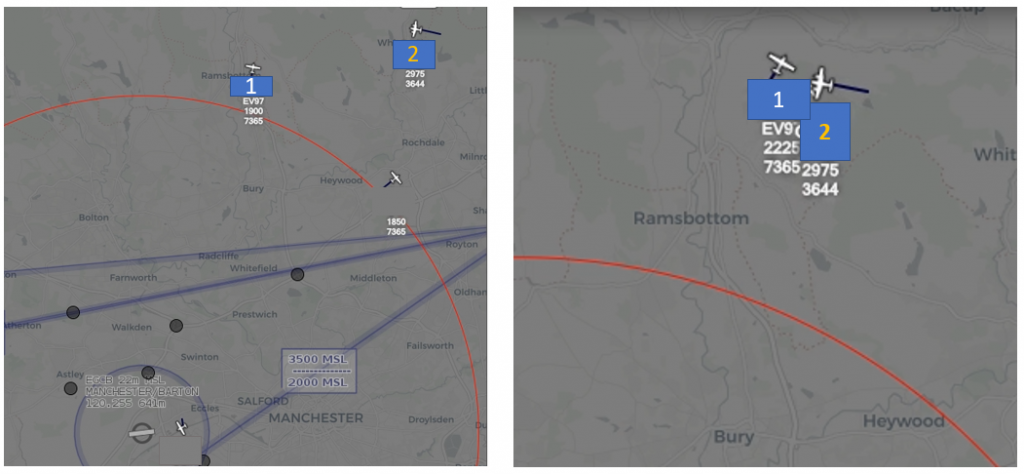

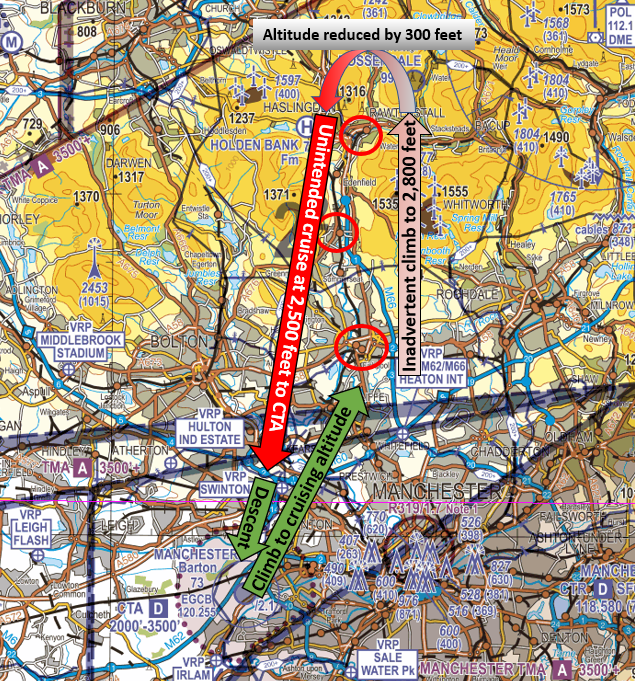

The Manchester radar controller was alerted to an aircraft squawking 7365 a few miles to the northeast of Barton aerodrome. The aircraft was indicating an altitude of 2,400 feet (1). The base of the Manchester CTA is 2,000 feet.

Mode S allowed the aircraft to be identified so the controller was able to contact the Barton Flight Information Service Officer (FISO). After a second call to Barton the aircraft descended.

The aircraft was inside controlled airspace for 3 minutes and 36 seconds before leaving the CTA. No other traffic was affected by the infringement.

The Barton FISO explained that the unit is part of an ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast) trial. This allows a FISO to offer generic traffic information (TI) to pilots operating within the unit’s designated operational coverage (DOC). Manchester Barton’s DOC is notified as 10NM/3,000 feet. Generic traffic information is given using phrases such as “in your vicinity”. The FISO could see that the frequency had not been changed to Warton after the aircraft left the unit’s DOC heading north. So issued TI on traffic that was approaching position from the east (see figure 1).

On recovery to Barton, the pilot informed the FISO that they were over Bury (figure 2). The FISO issued TI against an aircraft that was departing the ATZ northbound in a reciprocal direction.

At that point the aircraft was inside the DOC area, and the FISO commented to their assistant that, based on ADS-B altitude, the aircraft appeared high compared with the reported altitude.

The FISO was about to ask the pilot to confirm their altitude and pass updated information on the opposite traffic when the Manchester radar controller called to let them know the traffic was too high. The pilot was informed and carried out a descent out of the CTA to the correct altitude for an overhead join.

Pilot

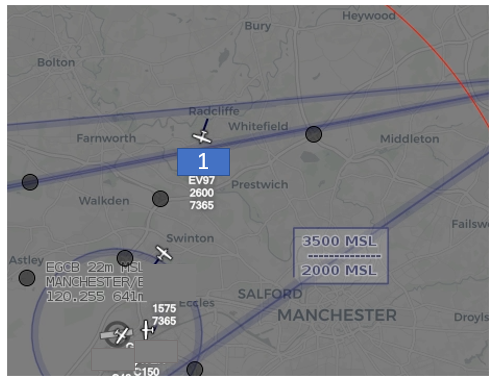

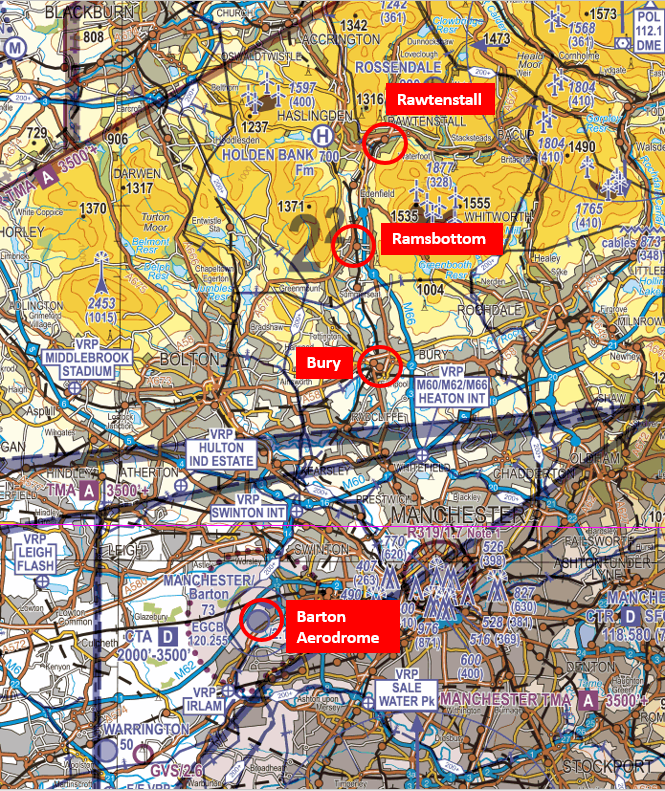

The pilot was carrying out a VFR sightseeing flight from Barton to Rawtenstall via Bury and Ramsbottom (figure 3).

On the day of the flight, met conditions were good. Visibility was in excess of 10km with some cloud detected at around 4,000 feet and a light and variable surface wind.

The pilot usually flew with a fellow pilot to supplement each other’s navigation, lookout and communications. On this occasion they were flying solo as their flying partner was unavailable. The pilot was flying the EV97 for the first time in some months. The pilot was using a 1:250,000 VFR chart and a basic version of a VFR moving map application on their mobile phone. This was secured in a mount on the right-hand side of the instrument panel due to the location of the 12V socket and position of the mount. The pilot explained that mounting a moving map is limited to the right-hand side as nothing can be fixed to the canopy. This meant that altitude information was very difficult to see from the left-hand seat. The aircraft was not equipped with either strobes or a beacon and, due to its bare aluminium colour, the pilot was aware that it was harder to see air-to-air than white microlights. The pilot remained on the Barton frequency throughout the flight and was in receipt of a Basic Service from Barton Information.

On the outbound leg, the FISO issued a warning of a much faster aircraft heading in a reciprocal direction. The microlight pilot became extremely anxious that the pilot of the conflicting aircraft would not become visual and all their focus turned to lookout, scanning all around in an unsuccessful attempt to catch sight of the aircraft. Although trimmed for level flight, the microlight had started a gradual climb from Bury to reach an altitude of 2,700 feet at Rawtenstall. Due to their focus on scanning, the pilot had not realised that the aircraft had climbed approximately 1,000 feet above their intended cruising altitude. On turning back towards Barton, and not realising they had climbed so much, a quick glance at the altimeter told the pilot that the aircraft was at *,800 feet. Having intended to fly at around 1,700 feet, the pilot mistakenly took this reading to be 1,800 feet. It was really 2,800 feet. The pilot started a gradually descent of 300 feet to what they thought was 1,500 feet, but was actually 2,500ft. This altitude was maintained the rest of the way back to the Barton overhead.

The pilot made two position reports en-route at this altitude of “Overhead Bury, one thousand five hundred feet” and “Half a mile north of Swinton Interchange at one thousand five hundred feet”. Overhead Barton, the FISO asked the pilot to check their altitude at which point they realised that the needle on the altimeter was pointing towards “2” not “1”. The pilot apologised whilst commencing a steep descent into the Barton circuit. The pilot added that a smaller aircraft or one with less performance in their proximity, “as often happens around Barton”, would not have caused them so much concern. But the warning of a larger aircraft travelling at a much higher speed triggered a serious worry about the risk of a mid-air collision had affected their concentration.

Figure 4 shows an approximate representation of the flight profile.

After the event the pilot analysed the occurrence, and noted a number of factors that led to them not noticing the higher altitude:

- Better conspicuity would lessen the stress of not being seen by other aircraft thereby reducing their focus on external scan and allowing some division of attention between lookout and instrumentation.

- A check of the basic version of the VFR moving map technology led them to note that their version did not offer warnings of possible vertical infringements.

- The mobile phone was positioned so far away from the pilot that they could not get an independent altitude check from that equipment.

- In previously flown aircraft, they recall seeing an additional display within the altimeter showing the altitude in numbers.

Causal factors

The pilot had planned to carry out a sightseeing flight to the north of Barton. The decision to use a 1:250,000 chart, allowing greater definition of the route features, was good based on the aircraft’s speed and the relatively short distance of the flight (approximately 15NM from Barton aerodrome). The use of a chart for navigation was supported by a VFR moving map.

However, in becoming distracted in trying to visually acquire conflicting traffic, an inadvertent climb resulted in the aircraft eventually reaching 1,200 feet higher than the intended cruising altitude.

The pilot was subject to confirmation bias. They knew they wanted to fly at or around 1,500 feet and the small needle on the altimeter pointed to 800 feet. In the pilots mind they expected to be at or around 800 feet. Having not flown the EV97 solo for some time, they were not surprised to have reached a slightly higher altitude by a few hundred feet.

Nothing in their plan or the small needle on the altimeter was to indicate that they were over 1,000 feet higher than intended. The confirmation bias could have been broken by one, or both of the following:

- The pilot normally flew with another pilot who has a tablet device with a ‘full’ version of a VFR moving map application. Had the pilot has such a device/version, even as a back-up to their using the 1:250,000 VFR chart, they would have had the benefit of a larger display which would have provided them with alerts as they climbed up to 2,800 feet with the Manchester TMA being above them at 3,500 feet. It would also have provided an alert on the inbound leg as they approached the Manchester CTA some 300 feet above the base altitude and then again as the CTA base stepped down to 2,000 feet.

These warnings are shown when the trajectory, both horizontal and vertical, would take an aircraft into a volume of airspace. An onscreen warning is often accompanied by an audible alert, the form of which depends on the type of airspace, and a thick border may be drawn on the map accompanied by large coloured arrows to highlight which piece of airspace is associated with the warning.

The CAA and safety partners actively encourage all pilots to incorporate the use of moving maps in both pre-flight planning and during flight. On this occasion, the pilot had not applied active Threat and Error Management in relation to their equipment in respect of the size and position of the display and the functionality of the ‘basic’ version of the application. In addition, the lack of options for the position of the mount may have played a part in accessing data from the moving map. - Had the pilot elected to obtain an air traffic service from the local LARS unit at Warton on 129.530MHz the chain of events may have been broken. On initial contact the pilot may have noticed the error when passing their details to the controller or, when they told Warton Radar that they were at 1,800 feet, Warton Radar would have noted an error in the Mode C when carrying out the verification and validation process during identification for a radar service. The Barton DOC is notified as 10NM/3,000 feet. When leaving the DOC area northbound, the pilot would have been better served getting a service from Warton.

The pilot became task saturated. While trying to visually acquire the aircraft for which they received information they failed to note an inadvertent altitude change. The pilot cannot be criticised for being risk aware and concerned of the developing situation. However, the use of an electronic conspicuity device on a larger display and/or the provision of an air traffic service are effective mitigations of mid-air collision. With mitigations in place capacity can be increased and stress levels reduced.

Having operated the EV97 for some time some skill fade may also have been a contributory factor.

Post-flight analysis

The pilot is commended for carrying out such detailed post-flight analysis of the occurrence (including the submission of a detailed and honest report), their approach to the factors surrounding the occurrence and for following Just Culture principles.

In addition they immediately engaged the services of a flight instructor to obtain remedial refresher training to ensure that issues could be addressed and rectified.

Focus on

- Use of Moving Maps

- Threat and Error Management – Read Threat & Error Management

- Confirmation Bias – Read SKYbrary Confirmation Bias

- Provision of an Air Traffic Service – Read Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS)

- Use of Frequency Monitoring Codes – Read Frequency Monitoring Codes (Listening Squawks)

(1) Please note that Mode A code and Mode C pressure-altitude have not been verified.

Other narratives in this series can be found on the Infringement occurrences page.

Infringement of Class D – Birmingham Control Area

| Aircraft Category | Helicopter |

| Type of Flight | Recreational Flight |

| Airspace / Class | Birmingham CTA / Class D |

Air traffic control

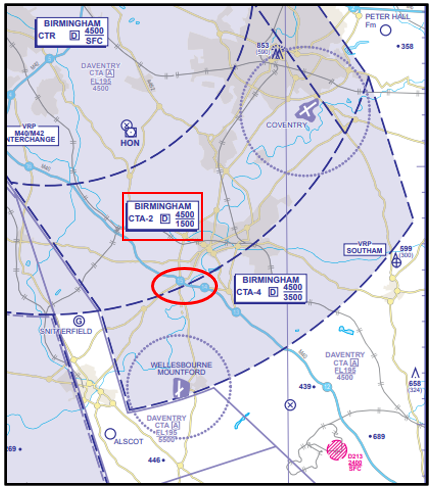

The Air Traffic Controller reported seeing an aircraft squawking 7000 enter the Class D CTA-2 near Warwick at 2,000 feet (Figure 1). It appeared to be following the M40 northbound. The aircraft descended to 1,800 feet then made a right turn and tracked eastbound climbing to 2,300 feet. The aircraft eventually turned southeast and left the CTA south of Coventry aerodrome. Multiple attempts to contact the aircraft were made on the frequency with no response.

Pilot

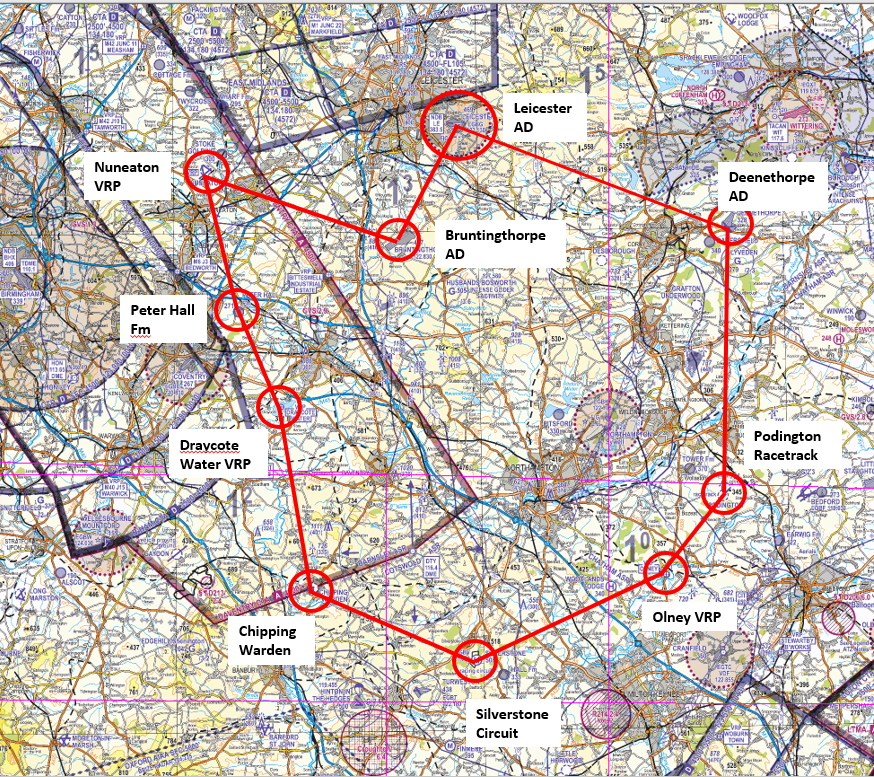

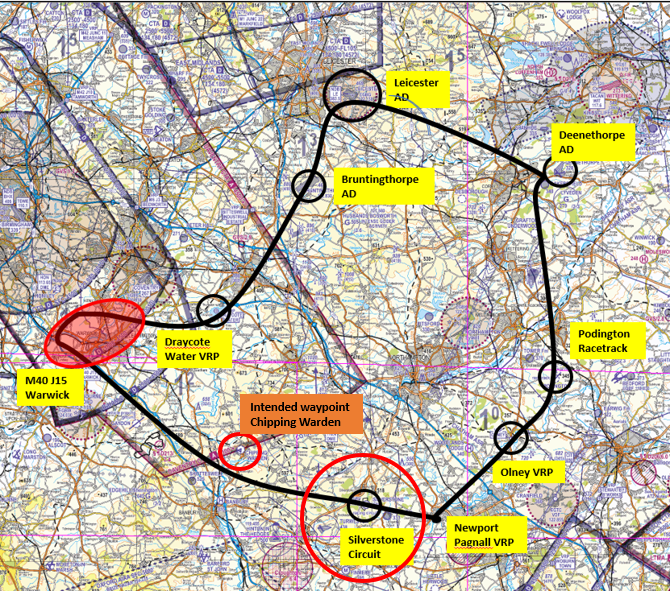

The pilot reported that they had planned a route to fly for their first solo flight as a PPL holder: Leicester Aerodrome – Deenethorpe Aerodrome – Podington racetrack – Olney VRP – Silverstone Circuit – Chipping Warden – Draycote Water VRP – Peter Hall Farm – Nuneaton VRP – Bruntingthorpe Aerodrome – Leicester Aerodrome.

The route had been planned on a VFR moving map on a tablet and transposed on a 1:250,000 VFR chart (figure 2). This was the first time they had used their personal iPad and the GPS stopped working 10 minutes after take-off.

As they had a well-prepared VFR chart, they continued with the flight having never had to rely on GPS previously when flying solo even though they had not flown the southern part of this route south of Northampton before.

After turning at Silverstone they had not noted the time and commented that they must have overshot Chipping Warden but, on seeing motorway, tracked it northwest bound until they could see Draycote Water VRP. By this time, they were beyond the area that was visible on the chart due to the way it was folded. As a result, they did not see the Class D CTA-2 with a base of 1,500 feet. Had they done so, they would have turned 180 degrees and tracked back down the motorway to avoid it.

The pilot added that they did not elect to obtain an air traffic service as they had to use the aircraft registration as their callsign instead of the instructors callsign used during training. In addition, as they routed northbound, they did not utilise the Birmingham Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) of 0010 and listen out on 123.980MHz as they had not been taught about FMC during their training. At the time of the flight, the pilot reported there to be scattered cloud (3-4 oktas) at about 2,300 feet with good visibility below.

Causal factors

The pilot had carried out good planning to carry out their first solo flight after the award of their licence. They had selected prominent geographical features as turning points and in accordance with good practice had planned to use a tablet-based VFR moving map with the paper chart as a back-up.

Shortly after departure, their GPS position failed as they were unaware that the tablet needed to be tethered to their phone as the tablet was not a cellular version.

The pilot lost situational awareness as to their position sometime after their waypoint at Silverstone Race Circuit (figure 3). Having been unable to locate the next waypoint at Chipping Warden, decided to follow the M40 motorway northbound. Due to the lack of aeronautical information available to the pilot, they entered the Birmingham CTA-2 to the southwest of Warwick at 2,000 feet where the base of controlled airspace is 1,500 feet.

Figure 3: Situational awareness as to their position was lost sometime after the waypoint at Silverstone Race Circuit.

In their pre-flight planning, the pilot applied good Threat and Error Management in marking the route on a paper chart. However, the manner in which the chart had been folded did not leave sufficient airspace and ground features visible to aid navigation. It is essential, as part of pre-flight preparation that you are not only familiar with the equipment functionality and limitations that you intend to rely on in-flight but that contingency measures are suitably prepared.

As the pilot routed northbound from Chipping Warden, as part of the initial plan, good practice would have been to employ the use of a Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) by selecting the Birmingham frequency of 123.980MHz and then selecting a squawk of 0010 Mode C as their intended route would have taken them close to the Birmingham CTA and well within the notified FMC area of recommended use (see UK AIP EGBG AD2.22 Flight procedures paragraph 7 and the chart at UK AIP ENR 6.80). The FMC is also annotated on the chart (figure 4). However, it was not incorporated into their plan as, at the time of the occurrence, the pilot was unaware of FMC and their use. Had they been aware, the infringement would have been resolved in a timely manner and navigation assistance offered at an early stage of the occurrence.

The pilot first became uncertain of their position when they missed their turning point at Chipping Warden having not noted their time at Silverstone. However, being unable to locate the aerodrome should have been a trigger to seek assistance from an Air Traffic Service Unit. A number of options were available including calling D&D on 121.500MHz for either a position fix or a steer to Draycote Water or calling Birmingham on 123.980 MHz for assistance or the LARS unit at Brize Norton on 124.275MHz (offering a service radius of 40NM daily between 0800 hours UTC and 1600 hours UTC).

However, due to the lack of experience of the pilot and then having only ever used an instructor callsign throughout their training rather than their aircraft registration. A lack of confidence in the use of the radio impaired their decision making. It is important for pilots to understand that air traffic control is there to help them and that controllers are used to offering navigational assistance when required.

A chart showing areas of responsibility for the UK LARS units can be found in the UK AIP at ENR6.11. Further details on units participating in the Lower Airspace Radar Services can be found in the UK AIP at ENR 1.6.4 (figure 5).

Post-flight analysis

This unfortunate occurrence occurred so soon after the pilot had completed their training due to gaps in knowledge, a lack of confidence in operating their radio in flight and lapses in Threat and Error Management.

The pilot is commended for carrying out such detailed post-flight analysis of the occurrence (including the submission of a detailed and honest report), their approach to the factors surrounding the occurrence and for following Just Culture principles.

Focus on

- Threat and Error Management – Read Threat & Error Management

- Use of Moving Maps

- Provision of an Air Traffic Service – Read Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS)

- Use of Frequency Monitoring Codes – Read Frequency Monitoring Codes (Listening Squawks)

Other narratives in this series can be found on the Infringement occurrences page.

Infringement of Class D – Birmingham Control Area

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing SEP |

| Type of Flight | Qualifying Cross Country PPL Training Flight |

| Airspace / Class | Birmingham CTA / Class D |

Met information

- TAF EGBB 070459Z 0706/0806 26009KT 9999 SCT030

- TAF EGBB 071056Z 0712/0812 27010KT 9999 SCT030

- METAR EGBB 071150Z 28009KT 240V320 9999 FEW035 BKN044 13/06 Q1013=

- METAR EGBB 071220Z 27011KT 240V310 9999 BKN042 14/06 Q1013=

- METAR EGBB 071250Z 28012KT 9999 BKN044 14/05 Q1013=

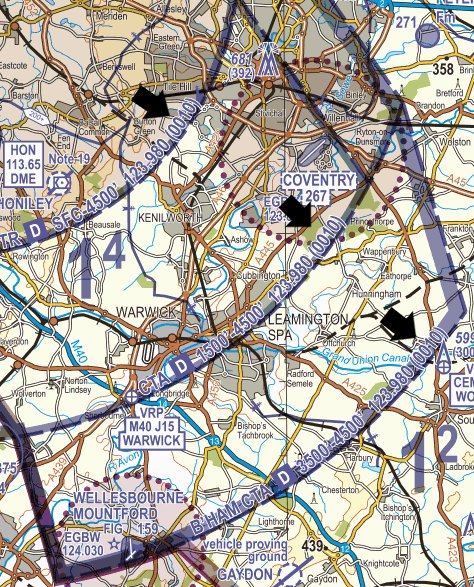

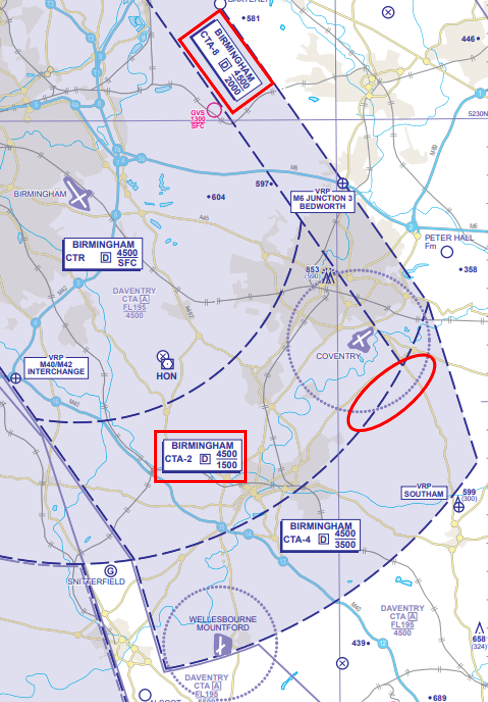

Air traffic control

The Air Traffic Controller reported being alerted, by the Airspace Infringement Warning tool, to an aircraft entering the Class D CTA-2 to the east of Coventry aerodrome at 2,500 feet, squawking 0010. The aircraft is seen to track east to west at the boundary with CTA-4 (figure 1). Due to another aircraft in the vicinity it takes a moment to interrogate the radar to establish, using MODE S, the identity of the infringing aircraft. The aircraft, having left controlled airspace tracked south and remained outside of controlled airspace until landing at Wellesbourne Mountford aerodrome.

Pilot

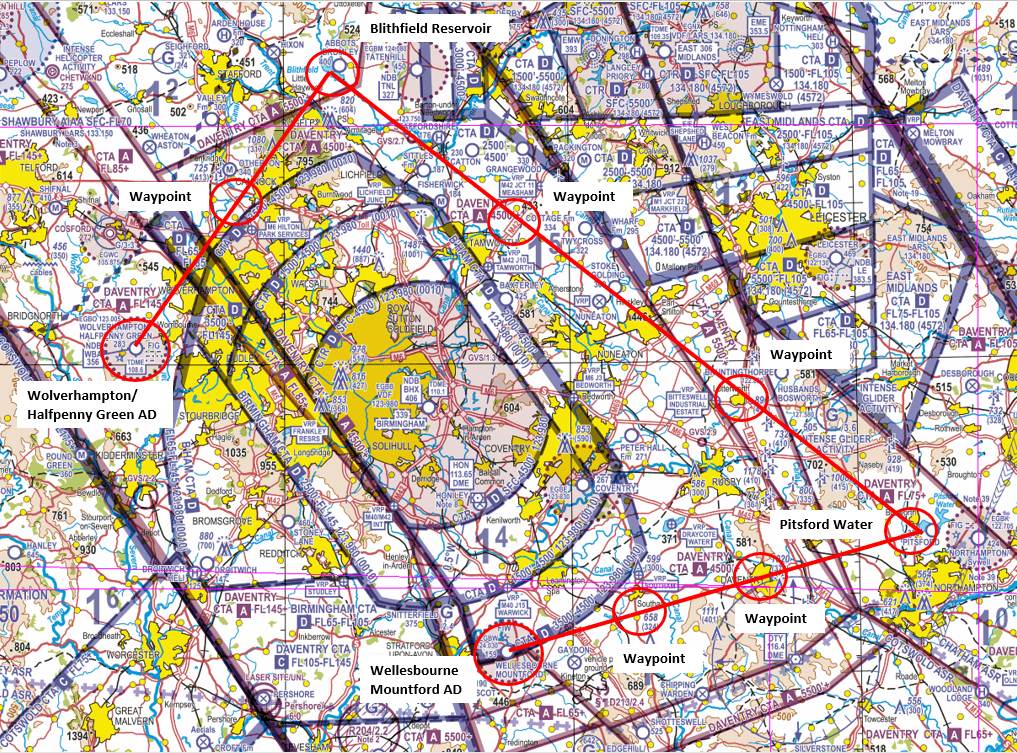

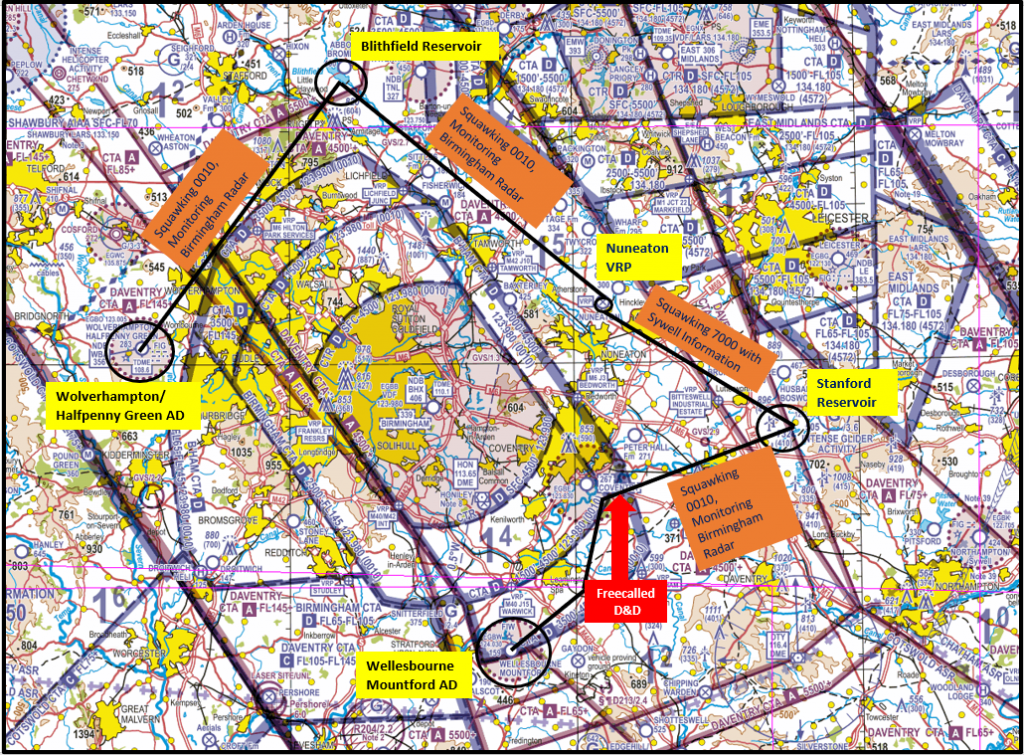

The pilot reported that they had planned the route to fly for their solo qualifying cross-country flight as follows:

- Wolverhampton/Halfpenny Green Aerodrome (EGBO) to Blithfield Reservoir – 22 NM

- Blithfield Reservoir – Pitsford Water – 48NM

- Pitsford Water – Wellesbourne Mountford Aerodrome (EGBW) – 29NM

The route had been planned on a VFR 1:500,000 chart (figure 2) and a neat and comprehensive Pilot Log (PLOG) (figure 3) was produced using the methods taught on the navigation module of the PPL course. Prior to departure, the student pilot and their instructor reviewed the plan and weather conditions. The reported conditions on that day seemed to be reasonable and the flight was authorised. They discussed using the Birmingham Frequency Monitoring Code of 0010 to allow for easier identification when flying close to Birmingham’s controlled airspace.

Although the PLOG has space for Regional QNH the pilot was aware of the risks of operating close to controlled airspace if a Regional Pressure Setting (RPS) is used and elected to use the Birmingham QNH.

Although the pilot had flown many navigation exercises and had done two solo navigation flights prior to the subject flight, they had only flown this particular route with their instructor on one occasion, three weeks earlier.

After departure, the pilot noted that the visibility was good, but the wind was much stronger than expected. This resulted in some challenges to maintain headings and the vertical instability of the air meant it was difficult maintaining altitude. Therefore, a large portion of their time was spent on maintaining the heading and altitude leading to a significant increase in workload in flying the aircraft. It also resulted in their calculated timings not being as accurate. The pilot had had changed frequency to monitor Birmingham Approach on 123.980 MHz and displayed the FMC of 0010. They had not spoken to them as they had been busy trying to maintain their heading and altitude as well as navigate.

During the leg between Blithfield Reservoir and Pitsford Water, the pilot became uncertain of their location and had circled above Nuneaton VRP several times to establish a positive location fix. Unfortunately, they had not reset the timer in the aircraft before setting off from this point. Continuing on with the route, they flew over a body of water (Stanford Reservoir) which they mistook for Pitsford Water. As the student neared what they thought was Pitsford Water, the pilot selected an SSR code of 7000 and called Sywell Information on 122.705 MHz to inform them of what they thought was their location. Shortly after leaving the turning point that had been mistaken for Pitsford Water, the pilot changed frequency back to Birmingham Approach and selected the FMC of 0010. Given that their timings were already out, compounded by their lack of familiarity with that area of the country, they did not realise that the lake/reservoir was roughly 10 nautical miles before Pitsford Water. Therefore, when the pilot turned onto the heading for Wellesbourne Mountford it was made too early and had put them on track towards controlled airspace (figure 4). Unfortunately, at that time, there were several other aircraft that were contacting the controller; therefore the pilot could not call them.

Realising, that they were flying in an area that did not correlate with the route plan and being unable to contact Birmingham, the pilot changed their heading to south and called Distress and Diversion (D&D) on 121.500MHz. They promptly provided the pilot with a position fix and, once aware of their location, the pilot was able to navigate to Wellesbourne Mountford. On landing at Wellesbourne Mountford, once parked, the pilot immediately telephoned their instructor at Halfpenny Green and explained the problems that they had experienced en-route.

Findings and causal factors

The pilot had carried out good planning which was endorsed by their Flight instructor; the plan incorporated prominent turning points and waypoints en-route. The weather was fit for solo VFR flight by a student although some unstable air resulted in increased cockpit workload associated with aircraft handling. The route was to be flown 1,000 feet above MSA which provided ample vertical separation from controlled airspace; in accordance with the Take 2 guidance (remaining 2NM laterally clear and/or 200 feet vertically clear of controlled airspace) the planned route demonstrated text-book Threat and Error Management in this aspect.

The pilot has also decided to incorporate the use of a Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) into their plan due to the proximity of the route to the Birmingham controlled airspace complex. On leaving the Birmingham frequency south of Nuneaton, they selected 7000 after selecting the Sywell Information frequency prior to transmitting. Once west of their turning point they again selected the Birmingham frequency followed by the FMC in accordance with good practice. The pilot was, however, not fully aware that when using an FMC, no transmissions are required with ATC unless responding to a call.

The student pilot was not flying with a Moving Map as their use had neither been taught in their training nor had they been encouraged to use one. The CAA actively encourage all pilots to incorporate the use of Moving Maps in both pre-flight planning and in-flight. TrainingCom (Spring 2020) states that it is important that instructors teach their students the use of GPS/GNSS aircraft systems when fitted to their aeroplane. The use of Moving Map displays should also be taught to enhance the student’s situational awareness once they have the basic Dead Reckoning (DR) navigation techniques. If the student uses these systems during solo-flying, this is permissible but they need to remember that they need to have the skills to later pass the licensing skills test. Therefore, it is the skills test that will be the time when the students DR Navigation techniques will be tested. Not only would a VFR Moving Map have provided the pilot with this enhanced situational awareness as they approached what they incorrectly thought was their turning point at Pitsford Water, but with a properly configured display, a visual and aural airspace warning would have been given alerting the pilot of their proximity to controlled airspace.

In the pilot’s mind they expected to see a body of water after Lutterworth, the second waypoint on the second leg. The pilot was on the correct ground track but due to a failure to incorporate the time taken to orbit at Nuneaton to establish their position, they became subject to confirmation bias. The sight of a body of water ahead on the route meant that the pilot’s expectations were confirmed, and the sensitivity of the error detection mechanism was reduced at a time when mental capacity was also taken up having just been unsure of their position and given the challenging air conditions. Despite Stanford Reservoir being less than a third of the size of Pitsford Water, the pilot was probably so relieved to see a lake, as planned, that they failed to compute that they had not yet reached their turning point. This chain of events could not have been broken when their position was passed to Sywell Information due to the lack of surveillance information available to the FISO.

The pilot first became uncertain of their position when the expected ground features from Pitsford Water to Wellesbourne Mountford were not visible (figure 5). By now back on the Birmingham frequency and squawking 0010, the pilot was unable to seek assistance from the radar controller. In need of assistance, the pilot immediately called D&D on 121.500MHz. Very few pilots revert to their training and may have continued on track in the hope of finding a recognisable feature whilst compounding the risks associate with an airspace infringement. On this occasion, the calm and logical execution of the Management technique of an identified Threat/Error enabled the pilot to establish a prompt resolution to the situation.

Any pilot who believes they are lost or temporarily uncertain of position should immediately seek navigational assistance from the appropriate radar unit. Alternatively, they should select code 0030 (FIR Lost) and contact D&D (callsign “London Centre”) on 121.500 MHz for assistance.

Post-flight analysis

Effective planning will always put you, as a pilot, in a position of strength for effective execution. But due to Human Factors, Threats and Errors will always exist and have the potential emerge.

In this occurrence, the pilot is to be commended for their handling of a stressful situation where an infringement was resolved in a timely manner. In addition, despite limited experience in the aviation community, they carried out a detailed post-flight analysis (including the submission of a detailed and honest report) and adopted a Just Culture throughout.

Focus on

- Threat and Error Management – Read Threat & Error Management

- Confirmation Bias – Read more at SkyBrary

- Use of Moving Maps

- Provision of an Air Traffic Service – Read Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS)

- Use of Frequency Monitoring Codes – Read Frequency Monitoring Codes (Listening Squawks)

Other narratives in this series can be found on the Infringement occurrences page.

Infringement of the Class D East Midlands Control Area 2 and overflight of active winch-launch glider sites

| Aircraft Category | Helicopter |

| Type of Flight | Recreational |

| Airspace / Class | East Midlands / Class D |

Met information

- TAF EGNX 111102Z 1112/1212 31007KT 9999 SCT020

- METAR EGNX 111450Z 31007KT 270V340 9999 BKN035 12/05 Q1026=

Air traffic control

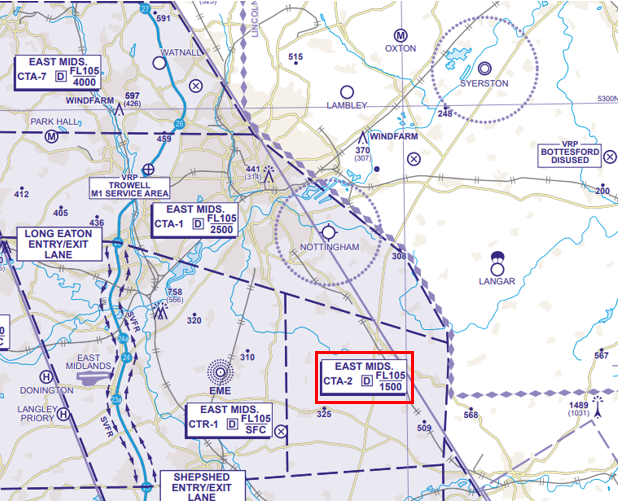

The Air Traffic Controller (Radar Director) reported vectoring a Commercial Air Transport aircraft on left base for and ILS approach to Runway 27 when an aircraft squawking 7000 was observed entering CTA-2 indicating between 2,000 and 2,300 feet on MODE C (Figure 1). The CAT aircraft, descending from 4,000 feet to 3,000 feet was instructed to stop its descent and turn onto a north-westerly heading. The aircraft levelled at 3,500 feet and passed approximately 4NM laterally and 1,000 feet vertical from the infringing aircraft.

The Air Traffic Controller (Radar/LARS) was operating in a bandboxed configuration (two frequencies combined, carrying out the functions of radar and LARS) and experiencing high workload due to multiple aircraft free calling East Midlands for air traffic services in Class G airspace and transits of controlled airspace. The infringing aircraft’s pilot established communications with LARS one minute and 7 seconds prior to entering controlled airspace but, due to the high workload, the pilot was instructed to standby and remain outside controlled airspace. The aircraft was then issued with a squawk, identified and instructed to vacate the CTA.

Pilot

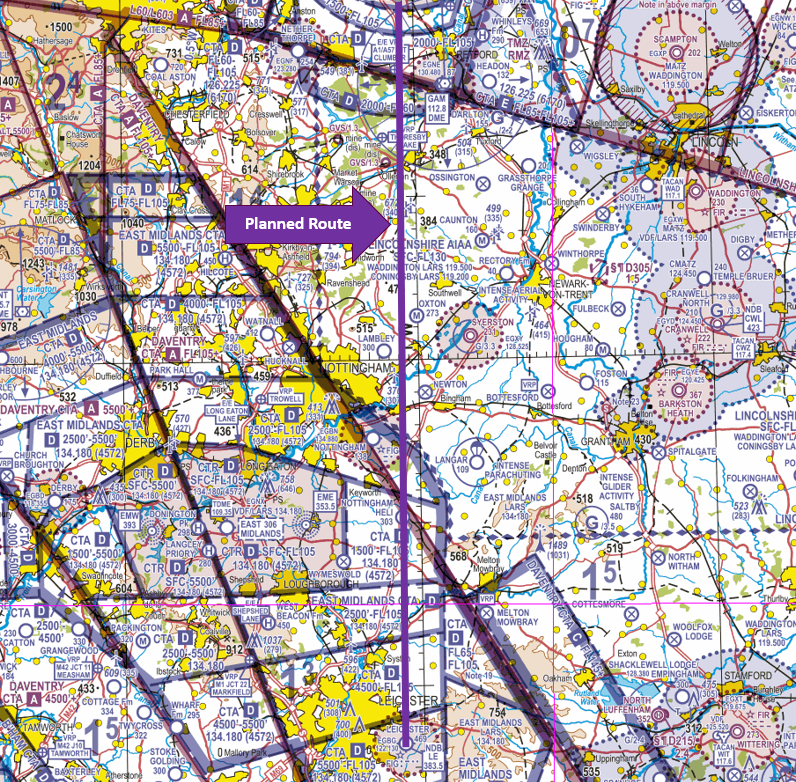

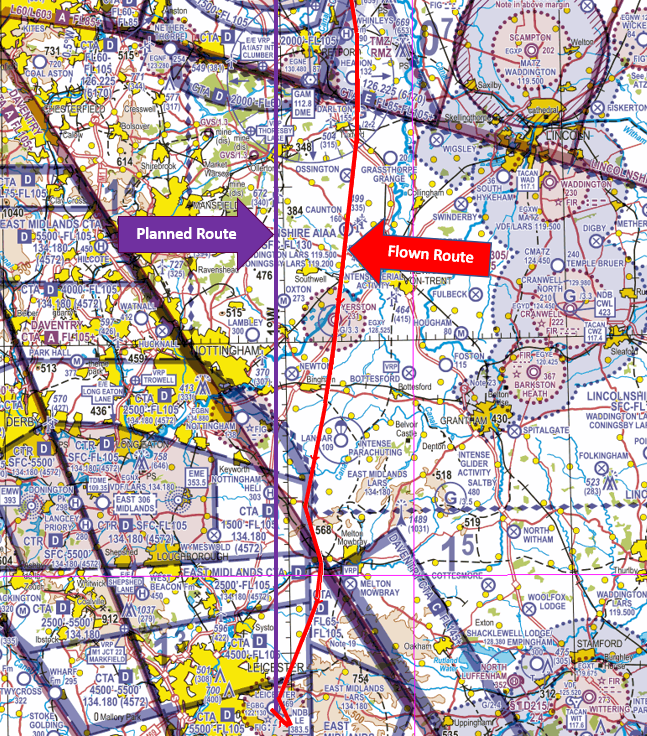

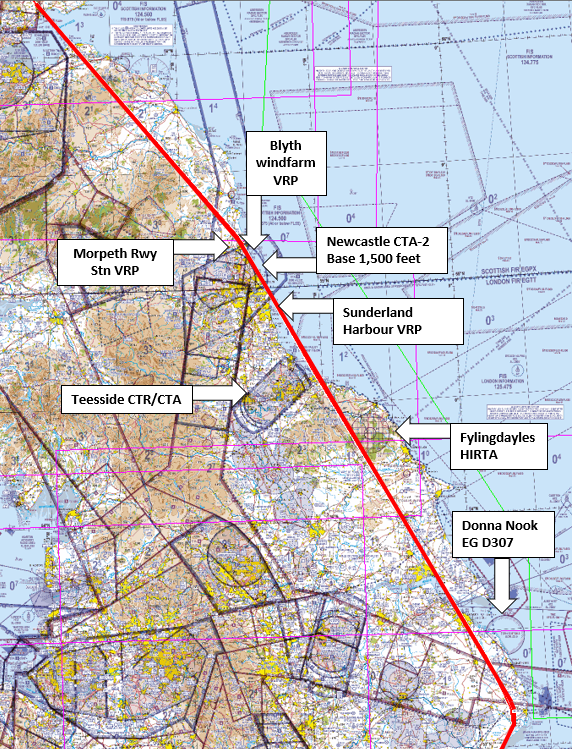

The pilot reported that they had planned the route to fly from a private site in North Yorkshire to Leicester via the Doncaster-Sheffield Airport overhead (Figure 2).

The route had been planned on a VFR Moving Map and the pilot was also carrying a VFR 1:500,000 chart. After the Doncaster-Sheffield Airport overhead, the route was planned to be flown through, or underneath, the East Midland CTA. However, whilst under Radar Control from Doncaster Radar and having been given clearance to route through their overhead, the pilot was asked instead to route to the East of their intended route. The pilot was almost east abeam Retford/Gamston aerodrome by the time they were cleared to continue on their intended route. At that stage, the pilot determined that they could now track direct to Leicester aerodrome east of the East Midlands airspace.

However, the pilot still wanted to obtain a Basic Service, but the frequency was so busy that it took some 10 to 15 minutes to get their first transmission made. Whilst in the ‘queue’ to receive a squawk from East Midlands Radar, the pilot realised that the Langar parachute drop zone was active. Eager to avoid the drop zone and keep an adequate lookout for the unusually large amount of traffic operating in the area, unfortunately the pilot allowed their track correction to the west to continue for too long before turning South. This caused them to inadvertently enter CTA-2 whilst at 2,000 feet. On being contacted by the LARS controller, the pilot immediately corrected their course eastwards and reduced their altitude as quickly as was safely possible, in order to vacate the CTA. The track flown is shown in Figure 3.

Findings and Causal Factors

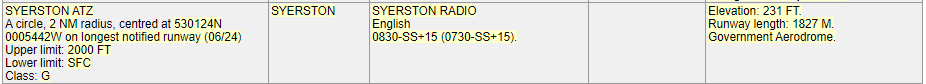

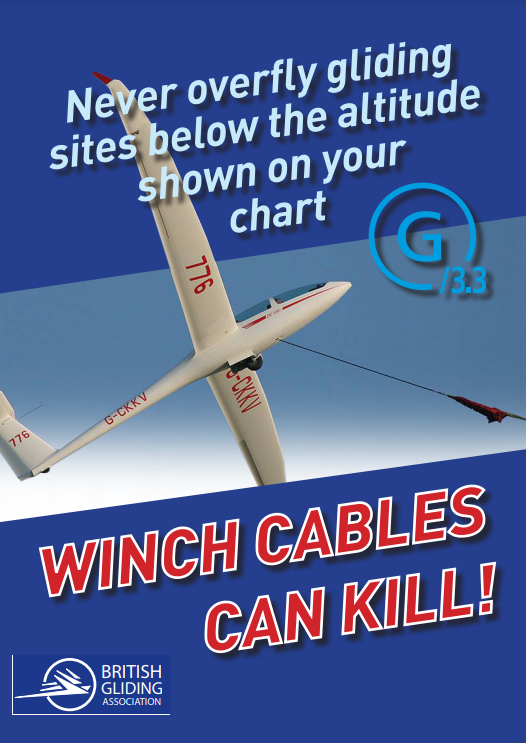

The pilot had formulated a sound primary plan to incorporate VFR transits of 2 volumes of controlled airspace: the Doncaster-Sheffield controlled airspace complex and the East Midlands CTA-2. However, lapses in planning result in no alternate plan (PLAN B) having been formulated in the event that a transit of either or both volumes of controlled airspace was not approved. When the pilot was issued a vector to route to the east of the Doncaster-Sheffield CTA they were now flying in an area that they had not planned to be in and had not considered from a Threat and Error Management perspective. As the pilot flew south, they overflew the following 2 winch launch glider sites at between 1950 feet and 2000 feet amsl: Darlton which is notified as operating sunrise to sunset (HJ) with cable launching up to 2,200 feet amsl and Syerston which is also notified as operating sunrise to sunset (HJ) with cable launching up to 3,300 feet amsl. In addition, the pilot flew through the Syerston Aerodrome Traffic Zone which, for the purposes of Rule 11 was notified in the UK AIP ENR2.2 (Other Regulated Airspace) as between 0730 hours and 15 minutes after Sunset from the surface to 2,231 feet amsl (Figure 4); on the date of the flight,, gliding was taking place at the aerodrome.

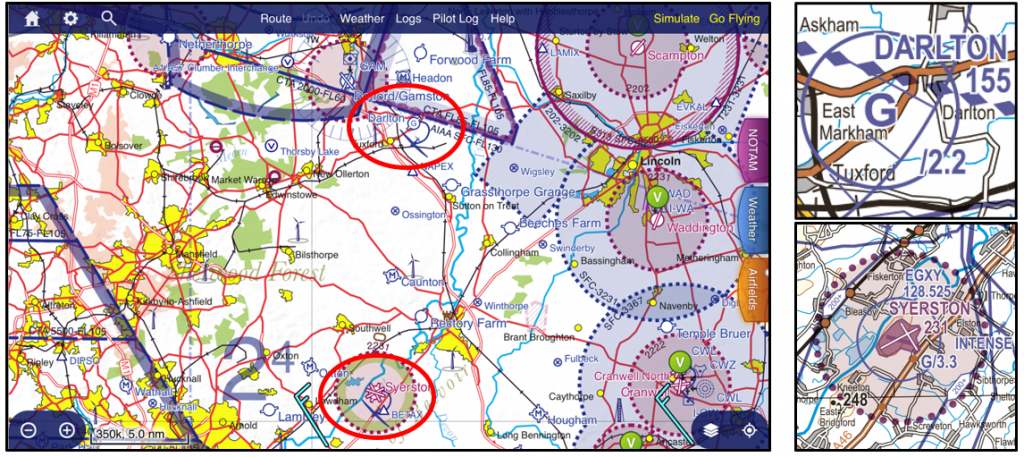

It is essential that whenever a flight is planned, an alternate route is considered by applying Threat and Error Management (TEM). Whilst air traffic control will make every effort to provide a crossing of controlled airspace on your requested route, it is good practice to anticipate that may not be the case. In formulating a ‘PLAN B’ it is essential to consider airspace structure and activities in the Class G airspace surrounding the controlled airspace that you plan to transit. As part of that planning, and application of TEM it is essential that you use the planning equipment to its optimum to consider all threats and risks. For example, on a paper VFR chart, winch launch glider sites are depicted with a blue circle and a G with figure in thousands of feet amsl to which the cable may extend e.g. G/3.3 signifying 3,300 feet. On the VFR Moving Map equipment that the pilot was using, the same area is depicted with a glider symbol but no maximum cable altitude in immediately visible. (Figure 5).

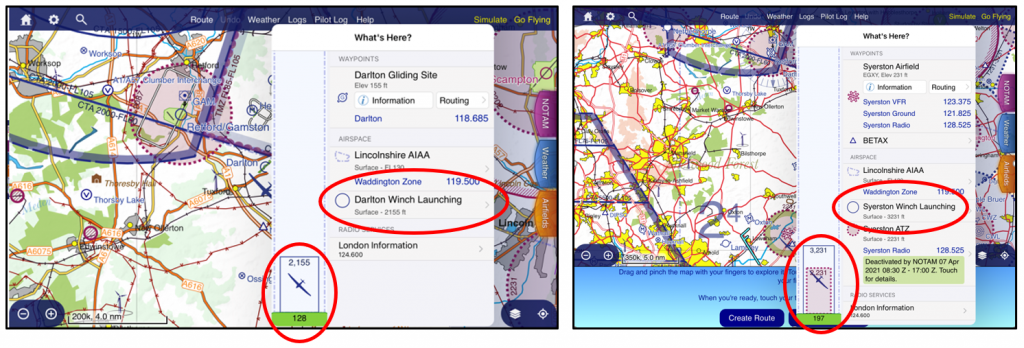

To establish the winch launch altitude, a pilot is required to press on the location and review the tab which appears on the screen. The information is shown in the list containing waypoints, airspace and radio services and in the vertical extent to the side showing the elevation of the site, the maximum cable altitude and any other airspace such as an ATZ (Figure 6). This information is also contained in the UK AIP at ENR 5.5 (Aerial Sporting and Recreational Activities).

It is important to note that any depiction of altitude relating to glider sites refers only to the maximum altitude of the cable. Glider activity can be expected to take place in the same area as either aero-tow or free-flight/soaring activity above the annotated altitude.

The pilot’s decision to route to the west of Langer and towards the East Midlands CTA also indicated lapses in effective situational awareness associated with ineffective TEM and pre-flight planning . The pilot commented that the East Midlands frequency was busy with multiple aircraft requesting a service. The pilot had already seen parachutes in the air from the jump aircraft at Langer. The wind at the time was from the west/northwest so the parachutists would have exited the aircraft to the west of the Langer drop zone. The pilot became fixated on maintaining an effective lookout as they were aware, based on how busy the East Midlands LARS controller was, that there were multiple aircraft in the vicinity of their track between Langer and East Midlands airport. This fixation resulted in Cognitive Lockup (the tendency of pilots to deal with disturbances sequentially) where they focused on the task of lookout and became reluctant to look at their Moving Map which would have not only given an alert as to their proximity to controlled airspace but would also have indicated that the pilot could have descended to at or below 1,500 feet and routed safely and effectively below CTA-2. The decision to switch or not to switch tasks may be influenced by a misperception of the expected benefits. This decision-making bias may mean that the benefits of switching have to be significant before the decision to switch is made. Furthermore, if an individual feels that the ongoing task is almost complete, they are more likely to stick to the ongoing task even if the new task is more urgent.

In addition, by making the decision to avoid Langer to the west (as the destination of Leicester lies to the southwest) the pilot was flying into a higher workload environment. A turn to the east would have added no addition distance to the flight and would have taken the pilot into less complex airspace and away from a traffic ‘funnel area’. In addition, it would have reduced cockpit workload, due to less radio telephony work. In their wider planning and decision making, had they considered applying the Take 2 guidance (Figure 7) of maintaining 2NM laterally from and/or 200 feet below controlled airspace, they may have altered their plan as they approached Langer to route into the more benign airspace to the east.

Post-flight analysis comment

Having an effective PLAN B will always put you, as a pilot, in a good position when external factors, such as weather, ATC restrictions or other traffic, influence your flight. It is relatively simple to make a sound plan and a backup plan or series of plans for each volume of airspace you fly in, or close to, and to incorporate effective Threats and Error Management in the various plans. It is, however, much harder to identify the onset and then override many of the Human Factors, such as Cognitive Lockup or Confirmation Bias that result in airspace infringements. That said, by being aware of their existence, it is possible to manage them; for example, a greater understanding of the risks in a particular sector of a route may also reduce the likelihood of cognitive lockup. In a multi-pilot operation, separation of tasks and roles between pilots, for example, by the captain passing control of the aircraft to the first officer while the captain deals with the malfunction, reduces the risk of both pilots fixating on the malfunction. Had their VFR Moving Map also been coupled to an Electronic Conspicuity (EC) device, this may have provided some situational awareness of participating EC traffic along with a timely warning of the proximity of controlled airspace.

Focus on

- Pre-flight Planning and the importance of a PLAN B

- Threat and Error Management – Read Threat & Error Management

- Use of Moving Maps

- Take 2 – Read TAKE2

- Cognitive Lockup – Read more at SkyBrary

- Provision of an Air Traffic Service – Read Lower Airspace Radar Service (LARS)

- Winch launch glider activity – British Gliding Association Winch cable warning poster

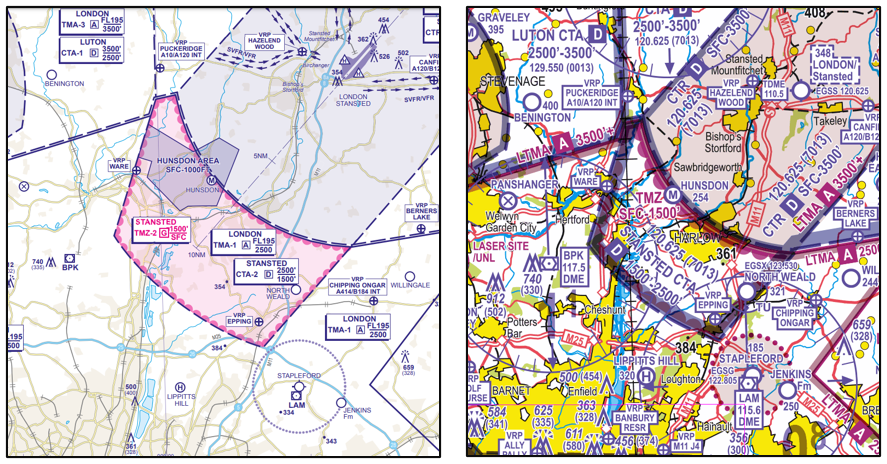

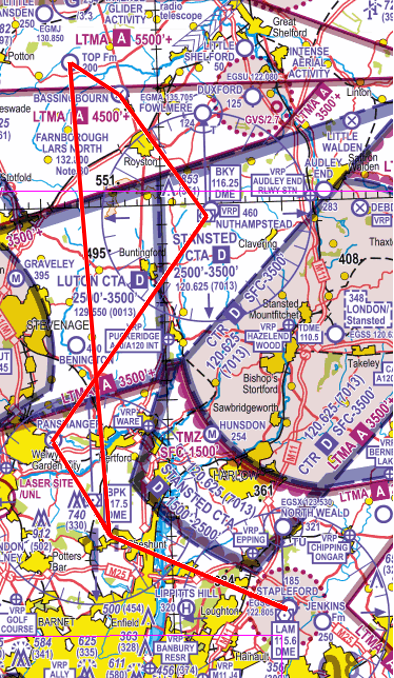

Infringement of the Class A London Terminal Control Area

| Aircraft Category | Fixed-wing SEP |

| Type of Flight | Recreational |

| Airspace / Class | LTMA / Class A |

Met information

- METAR EGLL 191450Z AUTO 21014KT 9999 SCT033 SCT039 BKN046 19/11 Q1015 NOSIG=

Air traffic control

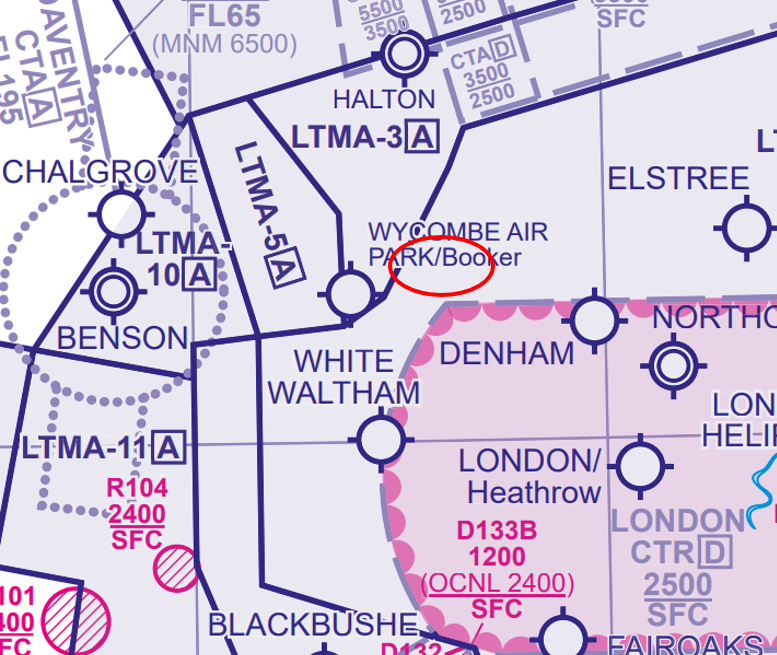

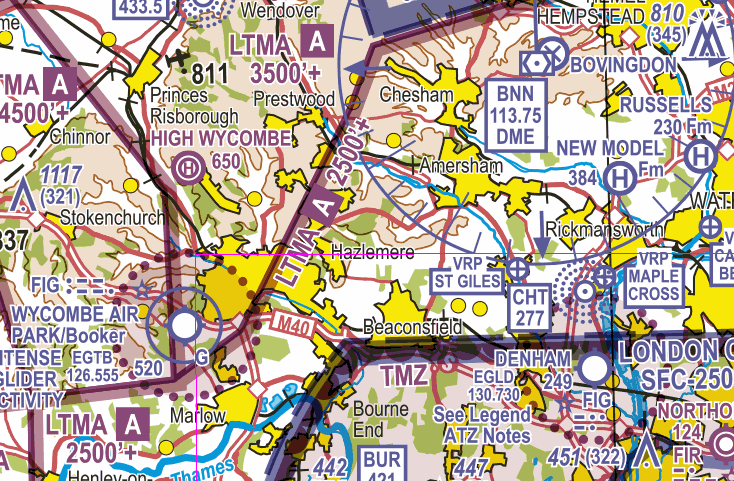

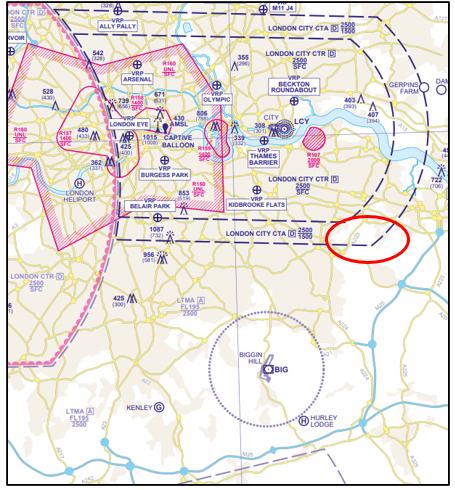

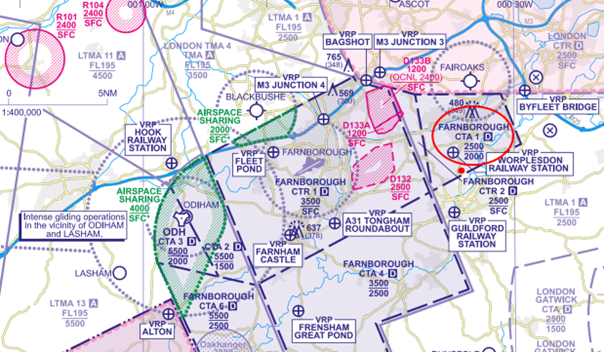

The Air Traffic Controller (Farnborough LARS West) reported providing air traffic services to five aircraft with a low to medium workload. The controller noticed an Airspace Infringement Warning (AIW) alert activate 3NM east of Wycombe Air Park/Booker aerodrome (Figure 1).

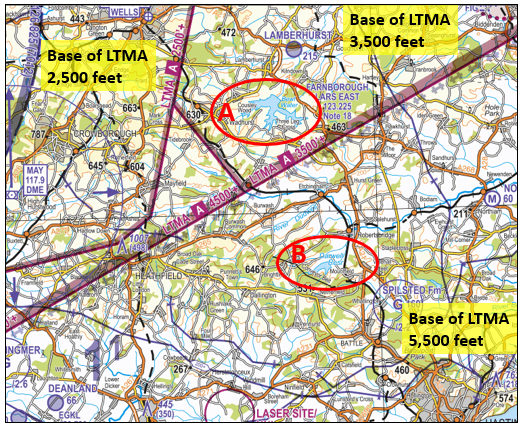

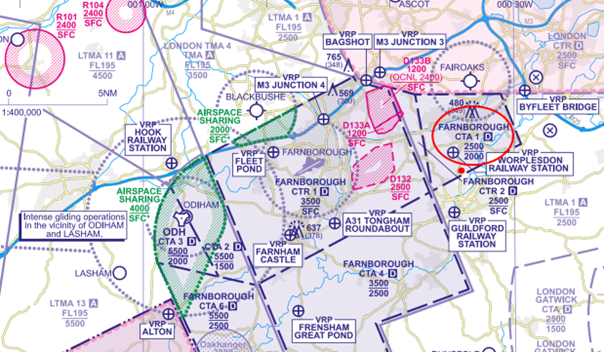

The AIW was associated with an aircraft squawking the Farnborough Frequency Monitoring Code (FMC) of 4572 indicating 3,300 feet where the base of the London Terminal Control Area (LTMA) is 2,500 feet (Figure 2).

The controller called the pilot who immediately replied. The pilot was then advised that the base of controlled airspace in their location was 2,500 feet. The pilot replied staying that they were descending. At the same time the Heathrow Special VFR controller called the Farnborough West controller to alert them of the event and was told that the subject aircraft was descending. On leaving controlled airspace, the controller obtained a level check from the pilot and verified that the aircraft’s MODE C was accurate.

Pilot

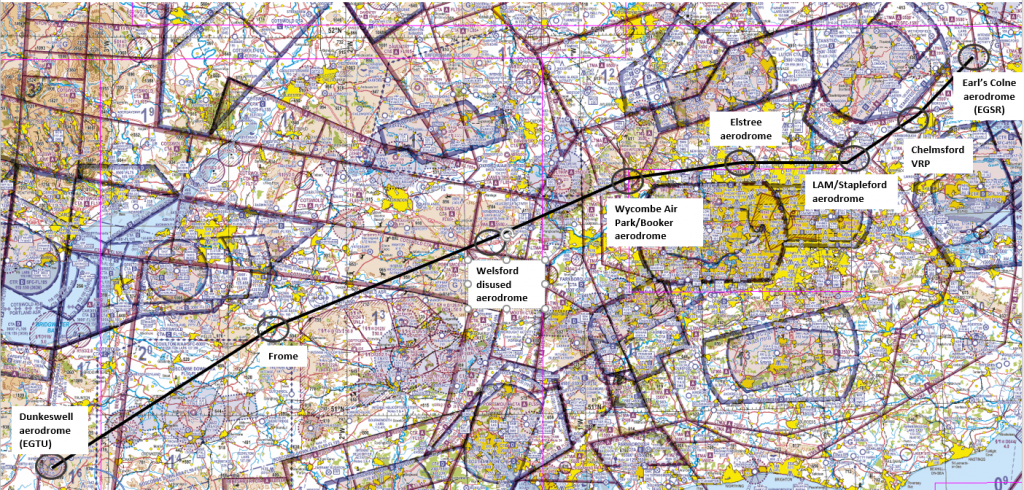

The pilot reported that they had planned a VFR cross country flight from Dunkeswell aerodrome in Devon to Earl’s Colne in Essex. It was the pilot’s first lengthy cross-country flight since the UK had entered the first COVID-19 lockdown in March 2020. The weather was reported as CAVOK and the route planned to be flown was:

- Dunkeswell – Frome – Welford Discussed aerodrome – overhead Wycombe Air Park/Booker aerodrome – overhead Elstree aerodrome – LAM/ overhead Stapleford aerodrome – west of Chelmsford VRP – Earl’s Colne aerodrome (Figure 3).

The route had been planned on a VFR moving map to route to the north of the London CTR/TMZ and was one that the pilot had flown many times.

As the weather conditions were good the pilot wanted to fly as high as possible to maximise the views from the cockpit. They flew at 2,500 feet until Welsford (7NM southwest of the Compton VOR (CPT)) when they commenced a gradual climb to 3,300 feet, reaching that altitude overhead Wycombe Air Park/Booker aerodrome. The pilot commented that when using their VFR moving map, there were so many different alerts, most of which they felt were unnecessary, which led to them to habitually cancelling the warnings.

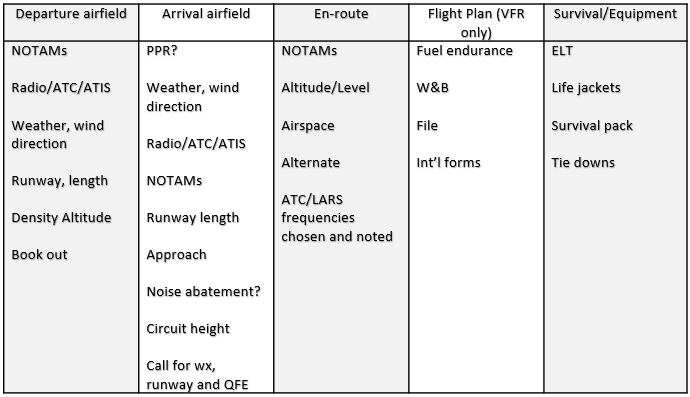

The pilot also stated that they used a personally prepared Flight Preparation checklist comprising five sections:

- Departure airfield;

- Arrival airfield;

- En-route;

- Flight plan (VFR only); and

- Survival/equipment.

In that list, “Altitudes” was included in the En-Route section only. After the occurrence, the pilot has added “Planned Altitudes” item to the “Flight Plan” (VFR Only) section. A copy of the checklist used at the time of the occurrence is at Table 1.

In addition, as soon as they were made aware of the occurrence, they submitted a detailed report and carried out effective post-flight analysis which resulted in revisions being made to their own check list to mitigate the risk of a recurrence.

Findings and Causal Factors